When Putinism lies in ruins, Russians will remember the fearless moral clarity of this prison letter from Darya Kozyreva, a medical student first expelled from university and then arrested for her antiwar actions.

‘Russia is wrapped in a heavy, impenetrable cocoon, a cocoon of silence. How many crimes the Putin dictatorship has committed, how many foreign cities it has seized and devastated, how many killings and tortures it has meted out, and the response to all these outrages is a deafening silence.

‘Many prefer not to know what is happening, to close their eyes and stop listening. Many deceive themselves, wishing to be deceived — after all it is so easy to believe blindly what the television says, even if it is broadcasting the most monstrous lies.

‘But many know perfectly well what this vile regime is doing. They endure the burden of their dissent, their outrage, their anger. And all the same, they are silent.

‘Just as any crime is committed with somebody’s tacit consent, so any dictatorship is maintained thanks to the people’s silence. A colossus with feet of clay will be worthless if all the dissenters speak out.

‘But they are silent.

‘One person thinks that everything has been decided, and that there is no reason for them, a minor figure, to get mixed up in this. Another hopes that others will say everything — but those others also find excuses to remain silent.

‘The real reason for this silence is human fear, visceral fear. No dictatorship can make everyone believe in it — therefore it constantly resorts to fear, its first and last instrument for subjugating the people.

‘Germans in the era of Hitler obediently shouted ‘Heil,’ understanding the consequences of disobedience; Soviet people in the era of Stalin were afraid to whisper in their own kitchens for fear of being denounced. The steamroller of repression doesn’t need to crush every dissenter, just a few demonstrative examples, and the rest will gag their own mouths.

‘The absurdity of Putinist repression has reached such heights that any trifle can become a pretext for persecution – and no one knows what one can say. The criminal in the Kremlin is satisfied; that’s exactly what he needs. As long as everyone is silent, his own skin will be safe.

‘That is precisely why one cannot stay silent. No, human fear is understandable: it is very difficult to risk one’s position, one’s future, one’s freedom. To say nothing of the fact that many have families — for these people, the fear is doubled. But will it be easier for these families to live under a dictatorship, under tightening screws, behind an iron curtain?

‘A dictatorship can continue to wreak its atrocities, its lawlessness, as long as it feels strength and power. Nothing will change as long as everyone remains submissively silent.

‘So perhaps the time has come to start speaking?

‘Everyone who can speak, must speak. The individuals who dared to speak up are now too few to move anything. Everyone must speak, who does not agree with the Moscow regime. Individuals can easily be put behind bars for their words, because they are individuals. But there are not enough prisons for everyone, for all the dissenters in Russia. Even if the regime builds just as many especially for them.

‘When, having overcome fear, everyone begins to speak out, it will time for Putin’s gang to be afraid.

‘No evil lasts for ever, any dictatorship will inevitably collapse. It can collapse of its own weight, like the USSR, or thanks to the uprising of the people.

‘Don’t let this dictatorship live any longer than it can. Speak out, people!’

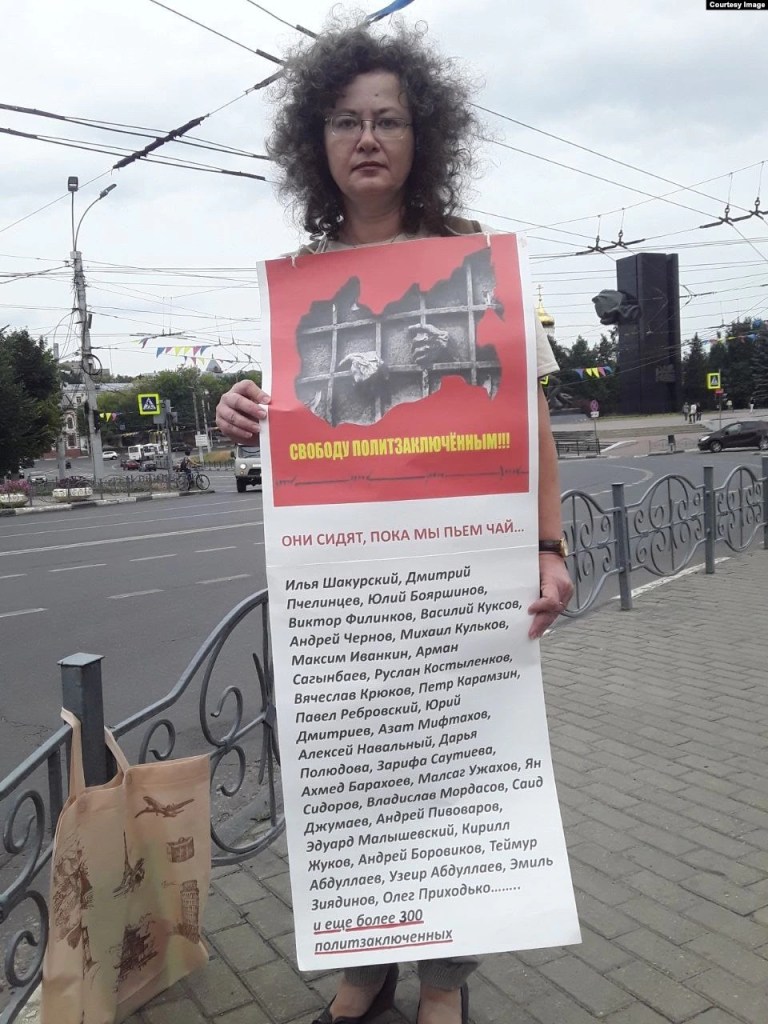

Source: Robert Horvath (X), 25 June 2024. Originally published in Russian by Holod on 25 June 2024 with this preface: “Daria Kozyreva is one of the youngest political prisoners in Russia. Until two years ago, she was in medical school at St. Petersburg State University and was politically active. In 2023, she was charged with an administrative offense for an anti-war post on [the Russian social media network] VKontakte and expelled from the university. On 24 February 2024 Kozyreva was detained after she pasted a leaflet containing a poem by the poet on the monument to [Ukrainian poet] Taras Shevchenko. Kozyreva faces five years for “repeatedly discrediting the Russian army.” She is in a pretrial detention center in St. Petersburg, where she is awaiting trial. There, she wrote a column about silence, fear and hope specially for Holod. We have published it as is.” Thanks to Simoni Pirani for the heads-up. Photo of Ms. Kozyreva, above, courtesy of RFE/RL.

Kneeling in the midst of the sedge, Linda Yamane sings faithfully an Ohlone song expressing gratitude to the plants after gathering material for her baskets. Once lost due to the Spanish colonization in the 18th century, the Ohlone basket-weaving skill was restored by Linda, who made her first tribal basket in 1994. Woven from willow sticks and sedge roots, the baskets played an essential role in the daily life of Ohlone people, who strongly connected to nature back to the old days. In the revival of the intricate basketry, Linda is motivated to bring about respect and appreciation of the traditional art, and the Ohlone spirit, living on in the mind of descendants, is thus aroused.

Source: Wood Culture Tour (YouTube), 23 June 2015

Source: “Reviving the Ohlone Language,” Smithsonian Magazine (YouTube), 23 February 2010

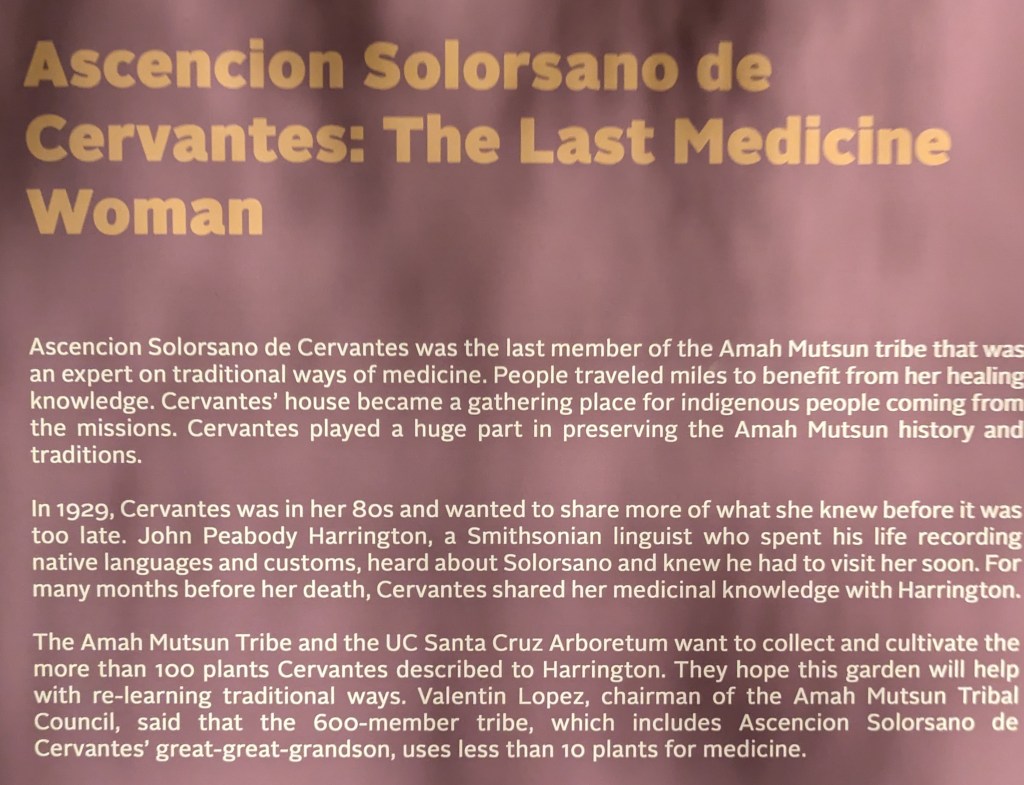

Source: Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, 30 June 2024. Photos by the Russian Reader

[…]

Desperate to talk to his wife, he signaled to a tall, skinny orderly who was cleaning his room that he wanted to use his phone. The Russian man quickly understood and when Mr. Shahi said, “Nepali, Nepali,” the cleaner opened a translation app on his phone.

“Get me a cellphone. I pay you later,” was Mr. Shahi’s message.

The Russian man smiled.

The same day, a new phone appeared.

[…]

They began to panic. In Russia, deserters are punished by military courts and can spend years in prison. But then they saw a taxi coming down a road and waved it down. Mr. Khatri said he frantically tapped open Google Translate on his phone and used it to tell the driver they were lost tourists and needed to get to Moscow. The driver took them all the way — 15 hours — and at the end, refused to take a single ruble.

Mr. Khatri worked with middlemen to get a flight to Kathmandu. Now back home in Rolpa, he said: “Some Russians are quite helpful. I could have died if that driver hadn’t helped us.”

Mr. Shahi had similar kind words for the Russian orderly. With the new phone, he spoke to his wife. She borrowed heavily from relatives — $8,000 this time — to pay another group of traffickers who said they could get her husband out.

On the morning of Jan. 23, Mr. Shahi gingerly stepped out of the Rostov hospital. He hobbled to a nearby market where a taxi was waiting for him. The driver communicated through a translation app, telling Mr. Shahi: Don’t talk. I’ll do the talking. If we get stopped, I’ll tell them you’re sick and headed to the hospital.

They drove all day to the one place that could help with the final stage of the escape: The Embassy of Nepal, in Moscow.

[…]

With his immersive documentary “Real,” Sentsov takes viewers inside Ukraine’s war trenches, after unknowingly turning on the GoPro camera on his helmet.

Oleg Sentsov was used to fighting Moscow even before he enlisted in the Ukrainian Defense Forces, shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

It’s just that previously, instead of a gun, he’d used his camera.

When Russian special forces arrived in Crimea in 2014, Sentsov was on the ground documenting the illegal annexation of the region. He was arrested, sent to Russia, and given a 20-year sentence on charges of “plotting terrorism.”

Following a coordinated effort by the European Film Academy, Amnesty International and the European Parliament with the support of directors like Ken Loach, Pedro Almodóvar and Agnieszka Holland — Sentsov was finally released on September 7, 2019, as part of a Ukrainian-Russian prisoner swap.

In November 2019, the Ukrainian film director and human rights activist was able to collect the 2018 Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought that was awarded to him by the European Parliament. Named after Russian dissident Andrei Sakharov, the award honors people who have “dedicated their lives to the defense of human rights and freedom of thought.”

Even while behind bars, Sentsov continued to work. Via covert letters smuggled out of prison by his lawyer, he directed “Numbers,” an adaptation of his own stage play about life in a dystopian, authoritarian state. The parallels to Sentsov’s own life were obvious.

But Sentsov is no knee-jerk nationalist. His 2021 feature “Rhino,” which premiered at the Venice Film Festival, is a look at the chaos that engulfed Ukraine following the collapse of the Soviet Union and how crime and corruption filled the resulting power vacuum.

‘Live’ from the trenches

But “Real,” Oleg Sentsov’s latest film, is unlike anything he’s made before.

It begins without explanation or warning. We are suddenly in a foxhole, hearing the frantic voice of a soldier over the radio in another trench, under attack from Russian forces and in desperate need of reinforcements.

During the first days of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, film director Oleh Sentsov joined the Ukrainian Defense Forces. In his role as an army lieutenant, he took part in several intensive battles – and during one, his BMP was destroyed by Russian artillery. In the aftermath, he became embedded in nearby trenches and tried to organize via radio the evacuation of part of his unit. All the while, his men were under constant attack, and eventually ran out of ammunition, making their evacuation all the more urgent. This military event on the Ukrainian-Russian front line positions was given the code name Real. This is the name of the film.

Source: Arthouse Traffic (YouTube), 18 June 2024

The voice on our end — that of “Real” director Sentsov, call sign “Grunt” — is trying to organize the evacuation of troops under fire and the resupply of his unit. Ammunition is running out, and the Russian forces — uniformly referred to over the radio as “f**kers” — are closing in.

“This is one of those very long days. It was part of the much-anticipated Ukrainian counter-offensive of last summer,” says Sentsov, speaking via Zoom on leave from the front.

“We had spent almost 10 days trying to get through the Russian defense line. We lost equipment, we lost weapons. But we were still in the same place. It was really obvious that we were losing many people, losing armaments, vehicles, everything. But even at that moment, we’d kept our belief that we could do something.”

Sentsov’s unit was sent deep into enemy territory but their armored personnel carrier was hit and they were forced to flee on foot. The director-turned-soldier found himself in a trench, with a handful of his squadmates. Other units were pinned down by enemy fire and running out of ammunition.

“They were almost entirely surrounded by enemies, and I was the only one who had a connection with them and could report back up to the higher commanders,” says Sentsov. “I was stationed a bit uphill and could communicate with both headquarters and the people in the trench.”

Camera on by accident

“Real” plays out as a single, unedited take — an hour-and-a-half long — as Sentsov repeatedly calls between the units and headquarters, trying to cut through the fog of war and get help to the soldiers before it’s too late. We see everything through Sentsov’s eyes, or rather, through the lens of the GoPro camera attached to his helmet.

The director hadn’t meant to be recording. He turned the camera on by accident when he was checking his equipment. It was weeks later, after the battle, that he discovered the footage on the camera’s memory card.

“At first, I thought it looked very random, I didn’t think it would be interesting for anyone and I wanted to erase it,” he says. “But then I started to watch it and I recognized that, oh my God, this is part of this very tragic event, with so many people in the trenches, cut off and surrounded by Russians. Our friends, my friends. People who will watch the movie may never see those soldiers and these situations but they can learn how tragic it was. They can see one of the most tragic days of the Ukrainian counter-offensive.”

“Real” has none of the stylistic flourishes that exemplify Sentsov’s narrative films. 2022’s “Rhino,” subtitled “Ukrainian Godfather” in its US release, is a slick gangster thriller that borrows heavily from the movies of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola to tell the story of the rise and fall of a violent delinquent — the Rhino of the title — who finds success in the chaos of 1990s Ukraine.

2020’s “Numbers,” which is set on a single stage, evokes the theatrical mimimalism of Lars von Trier’s “Dogville” or the plays of Bertolt Brecht.

In “Real,” the hand of the director is nowhere to be seen. Sentsov makes not a single edit. He adds no music or sound effects. Nothing is explained beyond what we see and hear on screen in real time.

“This is why I don’t call this a film or even a documentary but rather a pure document,” says Sentsov. “This is the video document that shows a part of the war, a very small glimpse of the war. But this war document captured on camera really shows us how cruel, how stupid, and, I can’t even find the words to describe it, how senseless war is… You get a very different perception of war if you only know it from war movies or from documentaries edited to make war look presentable. There’s always this component of heroism, everyone wants to emphasize this, to show dynamic, heroic action. But real war is very, very different.”

Sentsov calls “Real” an “immersive experience. You are thrown in and you only slowly start to understand what’s going on. It really drags you into the trenches.”

A document of war

Anyone expecting action will be disappointed. Instead we are forced to wait, along with the squad in the foxhole, with no idea what is happening around us and when the enemy will attack. “Real” captures the tension, the tedium, and the terror of war in equal measure.

“When I was young, I remember watching the movie ‘Platoon’ by Oliver Stone, and there’s a scene when one of the soldiers says: ‘Forget the word hero. There’s nothing heroic in war’,” says Sentsov. I couldn’t really understand that at the time because I grew up on very different movies that gave a very different perception of war. Now, after two-and-a-half years in an active war zone, I have to say I completely agree with that young man in the movie.”

Sentsov admits “the truth” he shows in his film may be painful for many, particularly inside Ukraine, to watch. The failure of the summer counter-offensive to break the Russian’s defensive line has shifted the conflict towards a brutal war of attrition.

“There are many things about the situation, about the reality of the war, that we are not discussing here inside Ukraine,” says Sentsov. “If someone would ask me how long it will take to reestablish control over the 1991 borders and to achieve a military defeat of Russia, I would say maybe it could happen in 10 years, but that would be a miracle.”

Instead of pretending that reality doesn’t exist, says Sentsov, it would be better, for Ukraine and the world, to “stare at the eyes of the truth, however painful. Otherwise, we are going to spend all our lives in an illusion that doesn’t relate to reality, to the real situation in front of us.”

Oleg Sentsov and David Sassoli at the Sakharov Prize award ceremony. Photo courtesy of Deutsche Welle

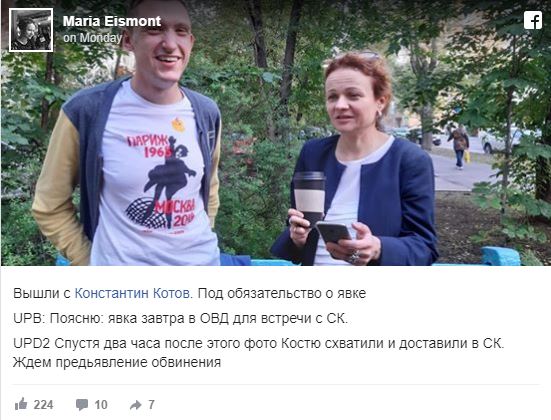

Oleg Sentsov and David Sassoli at the Sakharov Prize award ceremony. Photo courtesy of Deutsche Welle Konstantin Kotov. Photo by Adik Zubcik. Courtesy of Facebook and Mediazona

Konstantin Kotov. Photo by Adik Zubcik. Courtesy of Facebook and Mediazona Illustration by Mike Ch. Courtesy of Mediazona

Illustration by Mike Ch. Courtesy of Mediazona Nikolai Rekubratsky. Photo by Dima Shvets. Courtesy of Mediazona

Nikolai Rekubratsky. Photo by Dima Shvets. Courtesy of Mediazona

“Tomorrow, the whole world will write about this. I am proud of my profession. #FreeIvanGolunov…” Vedomosti.ru: Vedomosti, Kommersant, and RBC will for the first time…” Screenshot of someone’s social media page by Ayder Muzhdabaev. Courtesy of Ayder Muzhdabaev

“Tomorrow, the whole world will write about this. I am proud of my profession. #FreeIvanGolunov…” Vedomosti.ru: Vedomosti, Kommersant, and RBC will for the first time…” Screenshot of someone’s social media page by Ayder Muzhdabaev. Courtesy of Ayder Muzhdabaev

Photo by the Russian Reader

Photo by the Russian Reader Russia does not have to worry about a crisis of democracy. There is no democracy in Russia nor is the country blessed with an overabundance of small-d democrats. The professional classes, the chattering classes, and much of the underclass, alas, have become accustomed to petitioning and beseeching the vicious criminal gang that currently runs Russia to right all the country’s wrongs and fix all its problems for them instead of jettisoning the criminal gang and governing their country themselves, which would be more practically effective. Photo by the Russian Reader

Russia does not have to worry about a crisis of democracy. There is no democracy in Russia nor is the country blessed with an overabundance of small-d democrats. The professional classes, the chattering classes, and much of the underclass, alas, have become accustomed to petitioning and beseeching the vicious criminal gang that currently runs Russia to right all the country’s wrongs and fix all its problems for them instead of jettisoning the criminal gang and governing their country themselves, which would be more practically effective. Photo by the Russian Reader

Nach einem Showprozess folgt 20 Jahre Zwangszeit für dem Filmmacher Oleg Sentsov und zeigt uns den Neostalinismus vom System: Putin. Die FIFA bleibt feige und stumm. Schluss mit der Menschenverachtung – sofortige Freilassung von Oleg Sentsov!

Nach einem Showprozess folgt 20 Jahre Zwangszeit für dem Filmmacher Oleg Sentsov und zeigt uns den Neostalinismus vom System: Putin. Die FIFA bleibt feige und stumm. Schluss mit der Menschenverachtung – sofortige Freilassung von Oleg Sentsov!  Amnesty International, the world’s premier human rights organization, thinks there is a chance Network case suspect Yuli Boyarshinov (pictured here) and his ten comrades can get a fair trial in Russia, which has a 99% conviction rate. Photo courtesy of

Amnesty International, the world’s premier human rights organization, thinks there is a chance Network case suspect Yuli Boyarshinov (pictured here) and his ten comrades can get a fair trial in Russia, which has a 99% conviction rate. Photo courtesy of  Edem Bekirov. Photo courtesy of

Edem Bekirov. Photo courtesy of  Award-winning Ukrainian filmmaker and political prisoner

Award-winning Ukrainian filmmaker and political prisoner