Criminal Charges Filed in Tver Against Man Involved in Anti-Plato Road Tolls Protest

Criminal Charges Filed in Tver Against Man Involved in Anti-Plato Road Tolls Protest

Vlad Yanyushkin

OVD Info

September 23, 2020

In Tver, criminal charges have been filed against trucker Mikhail Vedrov, who was involved in a protest against the Plato road tolls system. Vedrov is accused of violence against an official (punishable under Article 318.1 of the criminal code). According to investigators, he slapped a traffic police officer. The court has placed Vedrov under house arrest. Officials attempted to prevent Vedrov’s lawyer and members of the public from attending the court hearing, and several people were detained.

On September 10 and 11, the Association of Russian Carriers (OPR) held a two-day protest in Tver against the Plato system. As the organization’s chairman Sergei Vladimirov told OVD Info, thirty-seven people from seventeen regions took part in the protest. Truckers called for abolishing the transport tax and making government spending on the transport industry more transparent. Drivers also held a founding congress to establish their own trade union.

On September 10, the protesters stopped outside the Plato data processing center on Red Navy Street. They expected Plato management to negotiate with them, but no one came out of the building. Instead, the police and the Russian National Guard came to meet them. Three regional OPR coordinators were detained for having posters on their cars featuring anti-Plato slogans. They were taken to Tver’s central police precinct, but soon released since the maximum time for keeping [people suspected of administrative violations, i.e., three hours] in police custody was exceeded. The protesters were given an undertaking to report again to the precinct to be formally charged with violating the rules for mass events (punishable under Article 20.2 of the Administrative Code), but the truckers failed to produce themselves at the precinct.

The second day of the protests on September 11 came off quietly. In the evening, as the truckers were leaving Tver, they were stopped by a traffic police patrol. Senior Lieutenant Sergei Nikishin asked Sergei Ryabintsev, who was behind the wheel, for his papers.

The entire convoy of truckers stopped, including OPR member Mikhail Vedrov from North Ossetia. According to investigators, “exhibiting direct criminal intent,” Vedrov approached the traffic policeman and, “realizing the public danger and illegality of his actions,” “struck at least one blow” to the officer’s neck. Thus, according to the formal written charges, the trucker caused the police officer physical pain and bruising of soft tissues in the neck.

Trucker Sergei Rudametkin provided OVD Info with an audio recording of a conversation with Ryabintsev, in which the trucker says that law enforcement stopped the convoy as it was leaving Tver. One of the officers asked to see the drivers’ papers. In response to a question about the grounds for this procedure, the police officer began yelling at everyone. At some point, the officer started shouting at Vedrov as well. Consequently, Vedrov was detained and accused of assaulting the police officer.

“There is nothing but the testimony of the victim [the police officer] and the testimony of the victim’s partner. Everything is based on the testimony of two police officers,” explains OVD Info lawyer Sergei Telnov. He added that Vedrov had invoked Article 51 of the Russian Constitution [which protects people from self-incrimination], so the defense lawyer did not have the right to answer some of our questions, for example, why Vedrov appears as if from nowhere in the police’s version of events, and whether he was in the car with Ryabintsev when the conflict with the police officer erupted.

Vedrov was taken to the central police precinct in Tver. Petersburg human rights activist Dinar Idrisov told OVD Info that over the course of the evening, the police investigator tried to pressure Vedrov to sign a confession, despite the lack of evidence. Around two o’clock in the morning, Vedrov was released under an obligation to appear before the investigator on September 14.

On the appointed day, Vedrov, accompanied by Telnov, reported to the Investigative Committee for questioning as subpoenaed. After a conversation with the investigator, they were given a summons for questioning, scheduled for the next day. On September 15, Vedrov was already interrogated as a suspect in a criminal case of violence against authorities. He was taken into custody.

Two days later, at Vedrov’s custody hearing, the bailiffs refused to let members of the public into the courtroom. Telnov explained that the official pretext was combating the spread of the coronavirus. Exceptions were made for one journalist and Vedrov’s wife and children, who had flown from North Ossetia for the hearing.

Telnov also had problems entering the courthouse.

“I got in the first time without no problems,” Telnov says. “Just before the hearing started, I went outside to talk, but when I tried to go back in they tried to stop me.”

According to Telnov, the bailiffs illegally demanded that he lay out the entire contents of his bag. When he tried to enter again, the bailiffs yielded.

Around four o’clock the judge retired to chambers to deliberate. It was then that Sergei Belyaev, editor of the Telegram channel I’m a Citizen! was detained and charged with failing to comply with the orders of a court bailiff (punishable under Article 17.3.2 of the Administrative Code) for recording video in the courthouse without permission from the presiding judge. The journalist was released after the arrest sheet was drawn up.

At the same time, OPR chair Sergei Vladimirov, who had come to support Vedrov, was detained in the courtyard in front of the court building. He was roughly shoved into a police car and taken to the Tver interior ministry directorate, where he was charged with disobeying the commands of a police officer (punishable under Article 19.3 of the Administrative Code) and left overnight in custody pending trial. He was released the next day.

Returning from chambers, the judge placed Vedrov under house arrest for two months, ignoring the prosecution’s request to remand the trucker in custody at a pretrial detention center. The prosecutor had argued that Vedrov could take flight, influence witnesses, and hinder the criminal proceedings.

Telnov explained in court that his client was unlikely to be able pressure the witnesses, since they were all police officers. Nor would he be able to destroy the evidence, since the whole case was based on the testimony of witnesses at the scene.

Photo of Mikhail Vedrov courtesy of the Association of Russian Carriers (OPR) and OVD Info. Translated by the Russian Reader. I have published numerous articles over the past several years about the inspiring militancy of Russian truckers.

[Three] years ago, on November 15, 2015, Russian authorities launched the Plato system (“Plato” is an acronym for “payment for a ton” in Russian) to collect tolls from owners of heavy-duty trucks traveling on federal highways. The authorities claimed their goal was to compensate for the damage the trucks caused to roads. It was decided the toll would be applied to owners of trucks weighing over twelve tons. Photo courtesy of Maxim Stulov/Vedomosti and RBC

[Three] years ago, on November 15, 2015, Russian authorities launched the Plato system (“Plato” is an acronym for “payment for a ton” in Russian) to collect tolls from owners of heavy-duty trucks traveling on federal highways. The authorities claimed their goal was to compensate for the damage the trucks caused to roads. It was decided the toll would be applied to owners of trucks weighing over twelve tons. Photo courtesy of Maxim Stulov/Vedomosti and RBC  The right to develop and implement Plato was awarded to

The right to develop and implement Plato was awarded to  Opposition politician Alexei Navalny and Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) lawyer Ivan Zhdanov asked that the courts declare the government’s agreement with RT Invest Transport Systems null and void. Their lawsuit was rejected first by the Moscow Court of Arbitration, and later by the Russian Constitutional Court. Photo of Alexei Navalny courtesy of Yevgeny Razumny/Vedomosti and RBC

Opposition politician Alexei Navalny and Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) lawyer Ivan Zhdanov asked that the courts declare the government’s agreement with RT Invest Transport Systems null and void. Their lawsuit was rejected first by the Moscow Court of Arbitration, and later by the Russian Constitutional Court. Photo of Alexei Navalny courtesy of Yevgeny Razumny/Vedomosti and RBC  Truckers in forty Russian regions protested against Plato in November 2016. They demanded Plato be turned off, a three-year moratorium imposed on its use, and the system be tested for at least a year. Photo by Yevgeny Yegorov/Vedomosti and RBC

Truckers in forty Russian regions protested against Plato in November 2016. They demanded Plato be turned off, a three-year moratorium imposed on its use, and the system be tested for at least a year. Photo by Yevgeny Yegorov/Vedomosti and RBC  When Plato was launched in November 2015, truck drivers paid 1.53 rubles a kilometer. Four months later, the authorities planned to double the toll, but after negotiations with truckers they made concessions, reducing the toll increase to 25%. Since April 15, 2017, the authorities have charged trucks 1.91 rubles a kilometer. Photo courtesy of Sergei Nikolayev/Vedomosti and RBC

When Plato was launched in November 2015, truck drivers paid 1.53 rubles a kilometer. Four months later, the authorities planned to double the toll, but after negotiations with truckers they made concessions, reducing the toll increase to 25%. Since April 15, 2017, the authorities have charged trucks 1.91 rubles a kilometer. Photo courtesy of Sergei Nikolayev/Vedomosti and RBC  However, even the discounted [sic] toll increase did not sit well with all truckers [sic]. On March 27, 2016, the OPR went on what it called an indefinite nationwide strike. Truckers protested the toll increases and demanded fairness and transparency at weight stations. Photo by Yevgeny Razumny/Vedomosti and RBC. [The slogans read, “Down with Plato!!! It’s Rotenberg’s Feeding Trough” and “We’re Against Toll Roads.”]

However, even the discounted [sic] toll increase did not sit well with all truckers [sic]. On March 27, 2016, the OPR went on what it called an indefinite nationwide strike. Truckers protested the toll increases and demanded fairness and transparency at weight stations. Photo by Yevgeny Razumny/Vedomosti and RBC. [The slogans read, “Down with Plato!!! It’s Rotenberg’s Feeding Trough” and “We’re Against Toll Roads.”]  In October 2017, the government approved a bill increasing fines for nonpayment of Plato tolls from 5,000 rubles to 20,000 rubles. If passed, the law would make it possible to charge drivers for violations that occurred six months earlier. The new rules were set to take effect in 2018. Photo of Dmitry Medvedev courtesy of Dmitry Astakhov/TASS and RBC

In October 2017, the government approved a bill increasing fines for nonpayment of Plato tolls from 5,000 rubles to 20,000 rubles. If passed, the law would make it possible to charge drivers for violations that occurred six months earlier. The new rules were set to take effect in 2018. Photo of Dmitry Medvedev courtesy of Dmitry Astakhov/TASS and RBC  Plato’s database has registered 921,000 vehicles weighing over twelve tons. According to the Russian Transport Ministry, during its first two years of operation, Plato raised 37 billion rubles for the Federal Roads Fund. In the autumn of 2017, the government selected three projects that would be financed by the monies raised by Plato: a fourth bridge in Novosibirsk and bypasses around the cities of

Plato’s database has registered 921,000 vehicles weighing over twelve tons. According to the Russian Transport Ministry, during its first two years of operation, Plato raised 37 billion rubles for the Federal Roads Fund. In the autumn of 2017, the government selected three projects that would be financed by the monies raised by Plato: a fourth bridge in Novosibirsk and bypasses around the cities of  Vehicles that transport people are exempt from Plato tolls, as are emergency vehicles, including vehicles used by firefighters, police, ambulance services, emergency services, and the military traffic police. Vehicles used to transport military equipment are also exempt from the toll. Photo courtesy of Gleb Garanich/Reuters and RBC

Vehicles that transport people are exempt from Plato tolls, as are emergency vehicles, including vehicles used by firefighters, police, ambulance services, emergency services, and the military traffic police. Vehicles used to transport military equipment are also exempt from the toll. Photo courtesy of Gleb Garanich/Reuters and RBC “Delivery for a favorite client.” A short-haul freight truck in downtown Petersburg, August 8, 2018. Photo by the Russian Reader

“Delivery for a favorite client.” A short-haul freight truck in downtown Petersburg, August 8, 2018. Photo by the Russian Reader

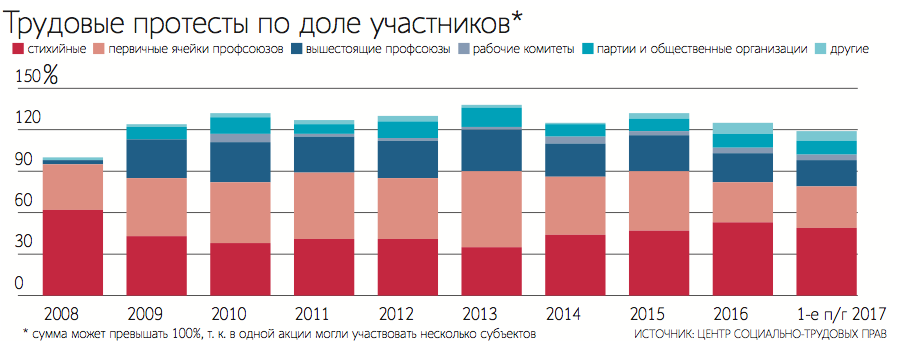

Labor protests in Russia in terms of percentages of those involved, 2008–first half of 2017. Red = spontaneous; pink = trade union locals; dark blue = national trade unions; gray = workers’ committees; light blue = political parties and grassroots organizations; pale blue = other. The percentage may exceed 100% if several actors were involved in the same protest. Courtesy of the Center for Social and Labor Rights

Labor protests in Russia in terms of percentages of those involved, 2008–first half of 2017. Red = spontaneous; pink = trade union locals; dark blue = national trade unions; gray = workers’ committees; light blue = political parties and grassroots organizations; pale blue = other. The percentage may exceed 100% if several actors were involved in the same protest. Courtesy of the Center for Social and Labor Rights

Russian President Vladimir Putin (second right) and National Guard chief Viktor Zolotov (third left) take part in a ceremony marking National Guard Day in Moscow on March 27. Photo courtesy of Mikhail Klimentyev/TASS

Russian President Vladimir Putin (second right) and National Guard chief Viktor Zolotov (third left) take part in a ceremony marking National Guard Day in Moscow on March 27. Photo courtesy of Mikhail Klimentyev/TASS