Two Petersburg Activists Remanded in Custody on Suspicion of Sexual Relations with 14-Year-Old Girl

Bumaga

February 21, 2019

This afternoon, a court in Petersburg remanded in custody two 18-year-old political activists: Vladimir Kazachenko, of the Vesna (Spring) Movement, and Vadim Tishkin, who attended opposition protests.

Police investigators suspect them of sexual relations with a female juvenile.

On the eve of their arrests, Kazachenko was visited at home by policemen who asked him questions about bomb threats. In early February, he had been involved in a protest on Nevsky Prospect. Tishkin claims police planted drugs in his house.

Civil rights activists argue the case bears all the hallmarks of political persecution.

Bumaga has summarized everything known about the case.

Kazachenko is an activist in the Vesna (Spring) Movement. After he was detained on Nevsky on February 9 while carrying a placard that read, “Open Russia Instead of Putin,” in support of arrested Open Russia activist Anastasia Shevchenko, he was charged with two administrative offenses, disorderly conduct and involvement in an unauthorized protest.

On February 19, Kazachenko was scheduled to appear in Petersburg’s Kuibyshev District Court at a hearing on both counts.

Kazachenko claimed that, a day earlier, at approximately eight o’clock in the evening, two plain clothes police officers knocked on his door and asked to be let in.

“They said through the door they needed to question us about the bomb threats of the last several days,” said Kazachenko.

As of today, February 21, there have been bomb threats leading to evacuations of public buildings in Petersburg for six consecutive days.

Our sources in Vesna informed us that officers at a neighborhood police station corroborated Kazachenko’s story about being visited by police due to the bomb threats. The police explained they needed him to make a statement.

Fontanka.ru writes that the police officers left around one in the morning. Kazachenko claims, on the contrary, the officers spent around an hour outside his door, but he did not let them in.

According to his lawyer, the next day, Kazachenko went missing an hour before his scheduled court hearing. By evening, activists from the Aid for Detainees Group discovered Kazachenko was being held in the criminal investigative department at the 15th Police Precinct. Another activist, Vadim Tishkin, was with him.

It is not known when and how they were detained.

Vladimir Kazachenko in court on February 21. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vladimir Kazachenko in court on February 21. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

The media wrote the activists had been detained on sex-related charges. This was corroborated, allegedly, by photographs posted on Telegram channels. Citing sources in law enforcement, Fontanka.ru wrote that Kazachenko and Tishkin had been detained, allegedly, for sexual relations with a 14-year-old female Vesna activist. 78.ru also noted police had found a beige-colored powder-like substance among Tishkin’s personal effects.

Several anonymous Telegram channels published similar reports. The posts featured photos from the so-called orgy, which took place under a Navalny campaign poster and involved the two activists and two young women. According to the Telegram channels, police found the photos when they were interrogating one of the female minors and confiscated her telephone. The faces of the alleged orgiasts were blurred in the published photos. Vesna argues the photos were deliberately leaked to the Telegram channels to make the case public.

According to an article published on the website Moika 78, the parents of the two female juveniles pictured in the photos filed criminal complaints against Kazachenko.

Later, the Aid to Detainees Group reported that Kazechenko and Tishkin were suspected of violating Article 135 of the Russian Federal Criminal Code (“Commission of indecent acts without violence by a person who has reached the age of eighteen against a person who has not reached the age of sixteen”).

Fontanka.ru wrote that the activists confessed their guilt, but the Aid to Detainees Group denies this. According to the civil rights activists, Tishkin admitted a narcotic substance was found among his personal effects, but he claims it was planted there.

Vadim Tishkin in court on February 21. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vadim Tishkin in court on February 21. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

On February 20, the Petersburg office of the Russian Investigative Committee reported that two local residents, born in 2000, had been detained on suspicion of committing indecent acts.

“The evidence gives us grounds to believe that, on February 18, 2019, the suspects committed indecent acts against a female juvenile, born in 2004, in an apartment on Grazhdansky Prospect,” wrote the agency.

The Investigative Committee stressed, however, it had “conclusive evidence” of the arrested men’s involvement in the crime: photos and videos found on the mobile telephones of the suspects and victims.

“The involvement of the suspects in political organizations of whatever kind has nothing to do with the current criminal case,” the Investigative Committee underscored.

According to the Aid for Detainees Group, the arrested activists initially received legal assistance from Russia Behind Bars and Memorial since, according to the civil rights activists, the case bore the hallmarks of political persecution.

Varya Mikhaylova, a spokesperson for the Aid for Detainees Group, explained to Bumaga that civil rights activists had made this assumption because Kazachenko had been involved in Vesna’s protests, while Tishkin had been detained during a protest against the pension reform on September 9, 2018. According to Mikhaylova, the two female minors were also involved in political activism.

Vladimir Kazachenko in the cage. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vladimir Kazachenko in the cage. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

The Vesna Movement also believe the case is politically motivated.

“I doubt whether they would put so much pressure on [Kazachenko] and make such a big deal of the case if he weren’t an activist. Besides, it would appear that he was missing for several hours before police investigators went public with their suspicions. None of the police precincts told us he was in their custody,” said Anzhelika Petrovskaya, the Vesna Movement’s press secretary.

Vesna commented on news of Kazachenko’s arrest on the evening of February 19. It said it believing meddling in the personal lives of activists was wrong.

Subsequently, Vesna has commented on the case on its Telegram channel.

“We hope people realize this is a victimless crime. Vladimir did nothing bad from an personal viewpoint. There was no violence involved. The movement believes we should help and support him,” wrote Petrovskaya.

Vesna has no intention of expelling Kazachenko from the movement. On the contrary, its activists are planning a crowdfunding campaign to support him in remand prison.

Two days after the activists were detained police, a court remanded them in custody. Their hearings took place in closed chambers.

Kazachenko was charged with having sexual relations with a minor in collusion with other individuals, a violation under Article 135 Part 4 of the Russian Federal Criminal Code, which stipulates a maximum punishment of fifteen years in prison.

Petrovskaya said Kazachenko had been sent to Remand Prison No. 1 for two months.

Vadim Tishkin in the cage. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vadim Tishkin in the cage. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Tishkin was also jailed for two months. The Petersburg judicial system’s joint press service did not mention the drugs charge, only that Tishkin was suspected of having sexual relations with a minor as part of a group.

Fontanka.ru writes that Tishkin is also suspected of attempting to steal a mug from a Starbucks on Nevsky Prospect.

____________________________

Yana Teplitskaya

Facebook

February 27, 2019

[…]

We spoke with Vadim Tishkin. He looked like a teenager, confused and completely ignorant of what a remand prison was. We spoke with him on Monday. He was delivered to the remand prison in the early hours of Friday morning. He had been without bed linens and other necessities the entire time. When police searched his house, they had let him take some things with him, but he had not chosen the best things to take. The remand prison should have issued him bed linens, of course, but apparently you have to insist on it for it to happen.

Concerning the criminal case, he said the police had not beaten him. They only insisted he take part in a drug sting, promising to plant drug in his home or on his person if he refused to cooperated. He refused to cooperate, and the police planted lots of drugs on him.

They knew right away the types and quantities of drugs they “found.” No forensic examination was needed.

The sting would have targeted his friend the political activist Vladimir Kazachenko.

(I wrote the first sentence of this story because I think it is terribly important that the first and second paragraphs are about the same person. A confused adult, who was a juvenile until recently, was made to choose between a prison term and a sting operation. Since he has a state-appointed defense lawyer, he will probably get a long prison sentence.)

We asked about telephones, because the Telegram channels who had sources in the police said the girl had voluntarily surrendered her telephone to police officers. In fact, as Vadim told us, she had not surrendered it voluntarily. It was forcibly confiscated, and the police had guessed the password since it was simple.

[…]

Thanks to Comrade K. for the heads-up.

____________________________

Former Sandarmokh Caretaker Sergei Koltyrin Sentenced to Nine Years in Pedophilia Case

Sergei Markelov

Novaya Gazeta

May 27, 2019

The Medvezhyegorsk District Court in Karelia has sentenced Sergei Koltyrin, former director of the district’s museum, to nine years in a medium-security prison camp and forbidden him to engage in teaching for ten years. The other defendant in the case, Severomorsk resident Yevgeny Nosov, was sentenced to eleven years in a prison camp.

Koltyrin was charged with indecent acts against a juvenile male in collusion with other individuals (Russian Criminal Code Article 135, Parts 2 and 4), sodomy against a juvenile male in collusion with other individuals (Article 134, Parts 3 and 5), and illegal possession of a weapon (Article 222, Part 1).

Nosov was indicted on the same charges, except the weapon possession charge. Both defendants refused to comment on the verdict.

The prosecution had asked the court to sentence Koltyrin to sixteen years, and Nosov to eighteen years, in a maximum-security prison camp. Prosecutor Andrei Golubenko told reporters the prosecution was satisfied with the verdict, but it would first have to read the text of the court’s ruling to decide whether to appeal it.

When asked how many victims there had been and whether the defendants had confessed their guilt, Golubenko refused to answer, citing the fact he could not divulge the particulars of the trial, since the evidence in the case had been presented in closed chambers.

Koltyrin’s defense lawyer, Konstantin Kibizov, was not present for the reading of the verdict, but he said his proxy would probably appeal the verdict.

Koltyrin and Nosov were arrested on October 3, 2018. According to police investigators, the men had repeatedly raped Nosov’s distant relative, who was twelve at the time. Both defendants partially admitted their guilt [sic]. The men were subsequently accused of having sexual intercourse with a juvenile male.

In August 2018, Koltyrin was appointed curator of the excavations in the forested area of Sandarmokh, as conducted by the Russian Military History Society. He had spoken negatively about the hypothesis that the site contained the graves of victims of the Finnish occupation of Soviet Karelia during 1941–1944. Koltyrin insisted the memorial site contained the remains of Soviet citizens executed during the Stalinist purges.

The mass graves of Stalin’s victims at Sandarmokh were discovered by a group led by Memorial Society historian Yuri Dmitriev, who was arrested in 2016 and charged with producing pornography depicting his juvenile foster daughter.

In April 2018, the Petrozavodsk City Court acquitted Dmitriev on the charges. However, the prosecutor’s office appealed the verdict, after which the case was sent to the Karelian Supreme Court for review.

In the summer of 2018, Dmitriev was indicted on new criminal charges. In addition to producing pornography, he was charged with committing violent sexual acts against his foster daughter.

Translated by the Russian Reader

_____________________________________

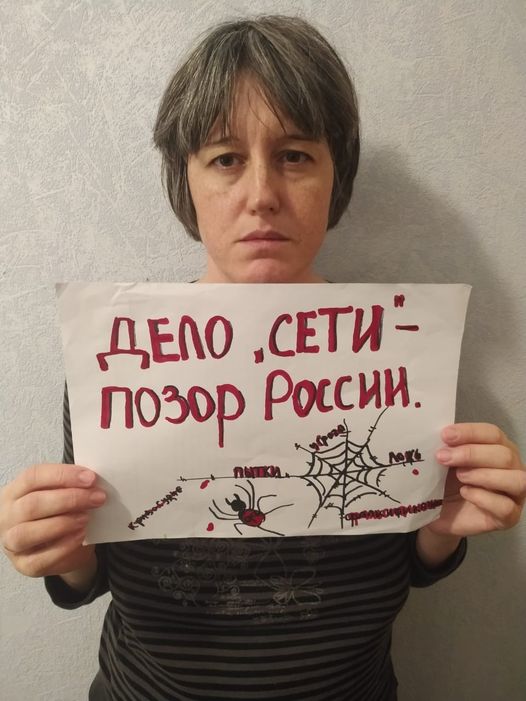

This post deals with four criminal cases against two very young opposition political activists in Petersburg and two middle-aged opposition historians in Russian Karelia who have played prominent roles in researching and publicizing the extent of the Great Terror in their part of the world.

What the cases have in common is that the men have all been accused and, in one case convicted, of sexual offenses against minors.

In the first case, two very young political activists in Petersburg stand accused of having sex with women only a few years younger.

In the cases in Karelia, the charges seem more serious—sexual acts against minors on the part of middle-aged men—but the article in the Russian Criminal Code is the same. If the activists and researchers caught up in the machinery of the Russian police state are found guilty (as one of them has been, only yesterday), they can be sentenced to long terms in prison.

I get the sense that most of the Russian civil rights community, the Russian press, the Russian opposition, and their supporters in the west do not want to touch these cases with a ten-foot pole, lest the taint of “sexual assault” and “pedophilia” touch them as well.

In fact, I would not have heard of the first two cases if I had not met another young Russian political activist who had the good sense to flee Russia when it was obvious the Prigozhin-controlled local press and social media set them up for the same charges as the ones now faced by Vladimir Kazachenko and Vadim Tishkin.

The whole world should know Karelian historian Yuri Dmitriev by now and understand the Putin regime simply cannot let its absurd frame-up, quashed once by the Petrozavodsk City Court, fall to pieces, so it upped the ante by accusing him of sexually assaulting his juvenile stepdaughter.

I know of at least one very large Russian civil rights organization that was so impressed by this obvious trickery they avoided sending a representative to Petrozavodsk for Dmitriev’s new trial.

They were scared to be seen there, apparently.

Maybe it has occurred to a lot of people who are determined not to open their mouths, but the police and security services in Russia have demonstrated in recent years they will stop at nothing to get their man or woman.

People who care about solidarity and glasnost have to be able to get over their squeamishness and see these cases for what they really are—a convenient means of sending the Russian opposition the message that no holds are barred in the regime’s war against them. At least, we have to presume innocence and admit the possibility the regime has no qualms about accusing anyone of any crime, no matter how heinous or, as in the case of the “teen sex orgy” in Petersburg, allegedly involving political activists, how banal.

It thus should go without saying that, when they are indicted on statutory rape or sexual assault charges, jailed in one of Russia’s harsh remand prisons, and abandoned by their former friends and political allies to the tender mercies of prison wardens, police investigators, and prosecutors, some people despair and let themselves be railroaded, knowing that the conviction rate of Russia’s courts is over 99%. {THE RUSSIAN READER}

Shohista Karimova. Photo courtesy of

Shohista Karimova. Photo courtesy of  “We shall never forget the memory of the heroes who fell in battle to liberate humanity from the yoke of fascism.” A nearly effaced Soviet war memorial in Berlin-Buch, June 1, 2019. Photo by the Russian Reader

“We shall never forget the memory of the heroes who fell in battle to liberate humanity from the yoke of fascism.” A nearly effaced Soviet war memorial in Berlin-Buch, June 1, 2019. Photo by the Russian Reader Vladimir Kazachenko in court on February 21. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vladimir Kazachenko in court on February 21. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga Vadim Tishkin in court on February 21. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vadim Tishkin in court on February 21. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga Vladimir Kazachenko in the cage. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vladimir Kazachenko in the cage. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga  Vadim Tishkin in the cage. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vadim Tishkin in the cage. Photo by Georgy Markov. Courtesy of Bumaga

Vladimir Putin playing hockey Moscow’s Red Square on December 29, 2018. Photo courtesy of Valery Sharufulin/TASS and

Vladimir Putin playing hockey Moscow’s Red Square on December 29, 2018. Photo courtesy of Valery Sharufulin/TASS and  How is the all-too-common Russian verb etapirovat’ translated into English? Screenshot of the relevant page from the website

How is the all-too-common Russian verb etapirovat’ translated into English? Screenshot of the relevant page from the website  Petersburg democracy activist Pavel Chuprunov, holding a placard that reads, “‘Yes, we tasered them, but it wasn’t torture. We were doing our jobs!’ Admission by the

Petersburg democracy activist Pavel Chuprunov, holding a placard that reads, “‘Yes, we tasered them, but it wasn’t torture. We were doing our jobs!’ Admission by the