“I demand an immediate cessation of all hostilities and an international investigation of all crimes committed. […] I call on all Russians to fight for their rights and against the dictatorship, and do everything to stop this monstrous [war],” a young woman named Victoria Petrova says confidently and clearly on the screen in courtroom 36 at the St. Petersburg City Court. The members of the public attending the hearing — they are thirty-three of them — applaud.

A month ago, Petrova was an “ordinary person,” a manager in a small family-owned company. Now she is a defendant in a criminal case, charged with disseminating “fake news about the army,” and has been remanded in custody in the so-called Arsenalka, the women’s pretrial detention center on Arsenalnaya Street in Petersburg. The case against her was launched after she posted an anti-war message on the Russian social media network VKontakte. If convicted, she could face up to ten years in prison. In the following article, The Village explains how, thanks to Petrova’s lawyer, the case of this unknown “ordinary person” has resonated with the public, why Petrova’s mother is not allowed to visit her, and what the prisoner herself has to say.

The Case

On the sixth of May, at seven in the morning, Center “E” and SOBR officers came to Petrova’s rented apartment on Butlerov Street with a search warrant. They seized phones, laptops, and seven placards on the spot. The next day, the Kalinin District Court remanded Petrova in custody in Pretrial Detention Center No. 5 for a month and twenty-five days.

“The investigator said that, if he had his way, he would have released Vika on his own recognizance. But he was instructed to petition the court to place her under arrest,” Anastasia Pilipenko, Petrova’s lawyer, told The Village.

A case was opened against Petrova under the new criminal article on “public dissemination of deliberately false information about the deployment of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.” According to the new law, any information on the so-called special operation in Ukraine that does not come from official Russian sources can be deemed “fake.” In Petrova’s case, the grounds for the criminal charges were a post on VKontakte, dated 23 March 2022, and the nine videos that she attached to it, featuring journalists Dmitry Gordon and Alexander Nevzorov, and grassroots activist and blogger Maxim Katz.

Who else has been arrested in Petersburg on criminal charges of spreading “fake news” about the Russian army?

Sasha Skochilenko

artist, musician

Olga Smirnova

activist

Maria Ponomarenko

journalist (she has been transferred to Barnaul)

Boris Romanov

activist

Total number of similar criminal cases in Russia: 53 (as of May 24)

Nearly 32,000 Victoria Petrovas are registered on VKontakte, and more than 1,800 of them live in Petersburg. The Victoria Petrova in question is depicted on her VKontakte pages as a woman wearing a light beanie, glasses, and makeup in the colors of the Ukrainian flag. She has 247 friends and eighty-nine followers.

Her post dated March 23 was deleted by VKontakte at the request of Roskomnadzor two days after it was published. But she made other anti-war posts, in which, among other things, Petrova recounts how she was jailed for ten days for taking part in a protest at Gostiny Dvor. In total, since the start of the “special operation,” she was detained twice on administrative charges.

When Center “E” [Center for Extremism Prevention] and SOBR [Special Rapid Deployment Force] came for Petrova on May 6, she thought at first that she would be charged once more under the Administrative Offenses Code. Realizing that now it was a matter for the Criminal Code, Petrova wrote her mother a detailed note explaining what to do with her apartment and her cat, and what things to send to the pretrial detention center, said Petrova’s attorney Pilipenko.

Pilipenko is now the only link between Petrova and the world: no one is allowed to see the prisoner except the lawyer.

The Lawyer

Pilipenko’s mother has her birthday on February 24. On the evening of the 24th this year, she and her daughter were going to drink tea and eat cake. But [the war] started early that morning.

“People who are also opposed to [the war] are taking to the streets. The police are putting them in paddy wagons. They face fines and arrests. Cake is canceled — I have work to do […] I am spending the night at a police station,” the lawyer wrote in her Telegram channel. She spent a month and a half working this way.

Pilipenko is thirty-five years old. She graduated from the Northwestern Branch of the Russian State University of Justice. For a year she worked as a clerk in the Leningrad Regional Court. “It was like going into the army,” she says. Usually clerks eventually become judges, but Pilipenko first became a lecturer, then a barrister. “I would never have become a judge, I would not have been able to make decisions that changed people’s lives,” she says.

Pilipenko specializes in criminal law. This is the toughest branch of the legal profession: the percentage of acquittals in Russia is negligible — 0.24%.

“But it happens that you can get a case dropped at the investigation stage. Or get the charges reduced to less serious ones. By today’s standards, that is tantamount to success for a defense lawyer,” says Pilipenko.

Pilipenko was not acquainted with Petrova until May 6, when the woman’s apartment was searched. The lawyer was asked to take the case by the Net Freedoms Project. The case is being handled by the Russian Investigative Committee’s central office.

“This means that there is no one investigator, that the entire investigative department is working on the case,” Pilipenko explains.

It was the lawyer who drew public attention to Petrova’s case by writing the following on May 11 on social media:

“Vika is an ordinary young woman. […] She has an ordinary life, goes to an ordinary gym, and has an ordinary cat. She has an ordinary job in an unremarkable company. […] Perhaps the only unusual thing about Vika’s case so far is just her ordinariness. She’s just like us. She’s not an activist, not a journalist, and not the voice of a generation.”

Vika

Victoria Petrova is twenty-eight years old. She was born in Petersburg, where she graduated from St. Petersburg State University’s Higher School of Management.

“Vika had a long braid, was very serious, gave the impression of an intelligent person, and got good grades. Intuitively, I feel that Vika is childish in a good sense, unspoiled,” Sofia, a classmate of Victoria Petrova’s, told The Village.

Another friend from school, Daria, in a comment to Mediazona, described Vika as a “born A student,” a “battler in life,” and a person who “was the most organized of all.”

“And her heart always aches over any injustice,” Daria said.

Pilipenko says that Petrova is “a very calm and organized person.”

“I was amazed by this at [the May 7 bail] hearing. People behave differently when they are arrested for the first time. Vika behaved with great dignity,” Pilipenko says.

Before her arrest, Petrova lived alone with her cat Marusya. The animal is now living with the heroine’s mother, while Maruysa’s owner is now at Pretrial Detention Center No. 5.

Arsenalka

Pretrial Detention Center No. 5 is located on Arsenalnaya Street, which is a deserted place dotted with small manufacturing facilities and the premises of the shuttered Krasnyi Vyborzhets plant, which was going to be redeveloped as a housing estate. A banner sporting the prison’s name and an image of the Bronze Horseman is stretched above the entrance to the Arsenalka. From the street side, the complex consists of a typical rhombus-shaped concrete fence, reinforced with mesh and barbed wire. A tower sheathed in corrugated iron juts out above it. On the right, behind an old brick wall, there is a a building in the shape of a cross — a psychiatric hospital “for persons who have committed socially dangerous acts in a state of insanity.” The old Crosses Prison itself, a remand prison for men, is about a kilometer away. Five years ago, all the prisoners were transferred from there to a new facility in Kolpino. The women remained in the pre-revolutionary red-brick Arsenalka complex.

Businesswoman Natalia Verkhova has described life at Pretrial Detention Center No. 5.

“The meter-thick walls and the thick iron doors outfitted with peepholes and bolts. The mattresses a couple of centimeters thick. The prison-baked loaves of bread, often burnt. The broken toilets. The concrete floors in basements where the ladies wait for many hours to be shipped out [to interrogations, court hearings, and other prisons]. The queues at the care packages office and for visiting inmates. The duffel bags chockablock with romance novels in the corridors.”

Former inmate Elizaveta Ivanchikova describes the largest cell in the Arsenalka (for eighteen inmates), to which Petrova, like all newcomers, was first assigned.

“There were nine bunk beds in [the cell]. There were bedside tables next to the beds. In the middle of the cell there was a large iron table with wooden benches. All of this was bolted to the floor. There was also a refrigerator, a TV, a sink next to the toilet, and the toilet itself, behind an ordinary door, without a lock.”

Pilipenko says that Channel One is constantly turned on in this cell and there are many unspoken rules for maintaining cleanliness.

“For example, you can only comb your hair in one place, because if eighteen ladies do it in different places, the hair would be everywhere,” says Pilipenko.

A head inmate keeps order, and at first Vika did not get on well with her. The head inmate did not like that the new girl did not know how to behave in the detention center.

“For example, when the guards come to toss the cell, you need to stand up and lock your hands behind your back,” says Pilipenko.

The conflicts were quickly settled, however, and Petrova was subsequently transferred to another cell.

This, according to Pilipenko, was preceded by an incident in the second part of May, during which plaster fell directly on the imprisoned women.

“Vika said that the girls were sitting and drinking tea when part of the ceiling collapsed on the table. Vika was not injured, but one inmate suffered bruises,” Pilipenko says.

The Telegram channel Free Sasha Skochilenko! reported that the plaster collapsed due to severe leaks: “The residents of the cell gathered the pieces of the ceiling, the largest of which weighed about three kilograms. The pieces were wrapped in sheets and the floor was swept.”

Petrova is currently in a cell for six inmates. During their last visit, when Pilipenko asked her how she was doing, Petrova replied, “You know, okay.” Petrova was surprised by her own answer.

“The letters she receives play a big role. Without them, she would not have any way to keep herself busy. This is the biggest problem in remand prison,” says Pilipenko.

The Letters

Petrova has received hundreds of letters, mostly from strangers, including from other countries. Petrova has told Pilipenko that she received a letter from a person who works in management at VKontakte. “He is upset that the social network played a role in my criminal case,” she told her.

“Vika definitely replies to all the letters. Except for those whose senders marked them with Z-symbols,” Pilipenko promises.

Petrova can correspond with other “ordinary people,” but it seems she cannot correspond with journalists. The Village sent her questions through her lawyer, but the sheet of paper with the answers was confiscated from Petrova right in her cell. Our correspondent then wrote to Petrova through the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service’s online FSIN-Pismo system. All three attempts that the The Village made to communicate with Petrova were not approved by the censor, and the negative responses came within a few hours, although the standard processing time is three days. Then, on the advice of Petrova’s lawyer, our correspondent sent all the same questions via FSIN-Pismo, but did not indicate that they were from the media. On the day this article went to press they were delivered to Petrova, but there has been no response from her yet. According to our information, other journalists have also failed to make contact with Petrova.

Petrova’s mother is also not allowed to see her daughter. According to the lawyer, one of the investigators said that “permission to meet with Mom will depend on the results of Vika’s interrogation as the accused party.” The investigators want Petrova to admit wrongdoing.

The Hearing

Victoria’s mother Marina Petrova lives in a three-room flat on Lunacharsky Avenue. Pilipenko filed an appeal against the order to remand her client in custody, hoping that “on grounds of reasonableness, legality, and humaneness” Petrova would be transferred to house arrest at her mother’s residence.

On the eighth of June, a hearing on the matter was held in the City Court. During the hearing, Pilipenko stated that her client was “actually being persecuted for voicing her opinion about the special military operation.” She also said that Petrova does not have a international travel passport and presents no flight risk, that there are no victims or witnesses in the case [whom the defendant theoretically thus might attempt to pressure or intimidate if she were at liberty], and that she had been charged with a nonviolent offense.

The defendant participated in the court hearing via video link from the Arsenalka. In her seven-minute closing statement, she explained what, in her opinion, had been happening for the last three and a half months in Ukraine.

Among other things, she said, “As a result of eight years of brainwashing by propaganda, Russians for the most part did not understand that [a war] had begun. Meanwhile, the completely immoral Z movement, ‘zedification,’ has been spreading across the country that once defeated Nazism. […] I do not feel any ideological, political, religious or other enmity towards the state authorities and the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation as institutions. In my anti-war posts, I said that people who gave and carried out criminal orders and committed war crimes should be punished for it.”

Judge Tatiana Yaltsevich denied the defense’s appeal. Petrova will remain in jail at least until the end of June.

On the evening of June 8, subscribers to the Telegram channel Free Vika Petrova! were warned that reposting her speech in court “could lead to criminal prosecution” — probably also under the article on “fake news” about the army.

The next day, Petrova commented on her speech to her lawyer.

“She says that since she has already become a political prisoner, she cannot help but use the court hearings as a means to talk about what is happening. She has not remained silent before, and she has even less desire to be silent now that many people will hear what she has to say,” reports Pilipenko.

Source: “‘An ordinary person’: the story of Vika Petrova, who wrote a post on VKontakte and has been charged with spreading ‘fake news,’ but refuses to give up,” The Village, 9 June 2022. Thanks to JG for the story and the heads-up. Translated by Thomas H. Campbell. Ms. Petrova’s support group has a Telegram channel and is circulating an online petition demanding her release.

Dmitry Pchelintsev. Archive photo courtesy of RFE/RL

Dmitry Pchelintsev. Archive photo courtesy of RFE/RL

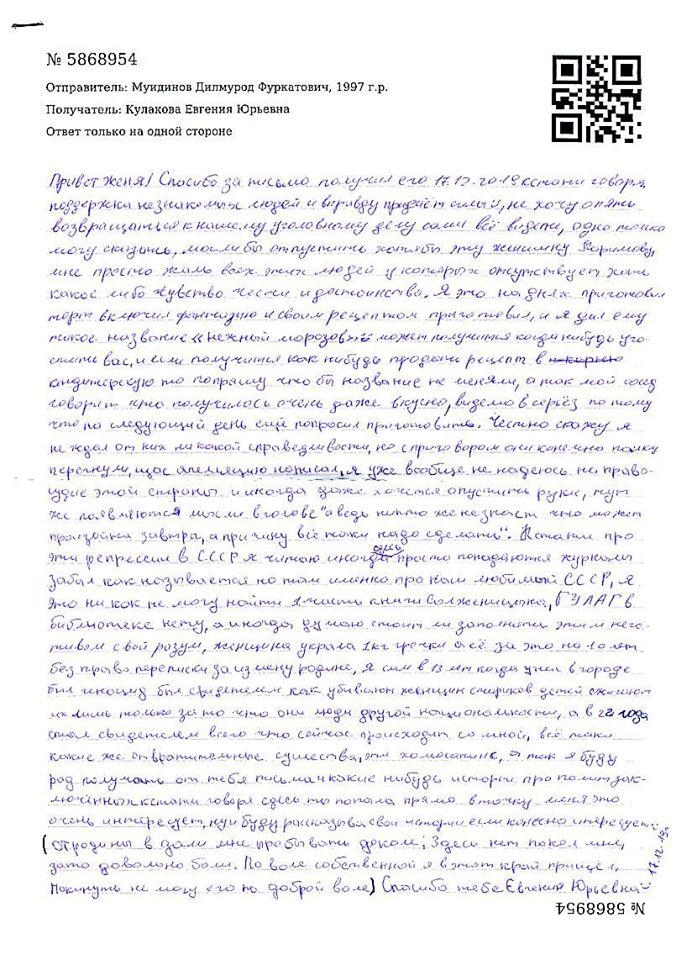

Dilmurod Muidinov. Photo courtesy of Regnum and Jenya Kulakova

Dilmurod Muidinov. Photo courtesy of Regnum and Jenya Kulakova

An excerpt from the 2016 Global Slavery Index

An excerpt from the 2016 Global Slavery Index