The case of Sasha Skochilenko is a striking example of the absurdity of today’s Russia. She faces ten years in prison for her anti-war protest at a supermarket.

Bumaga has discovered that Sasha’s protest was reported to the police by an elderly woman. The security services organized a special operation to capture Skochilenko. Today the young woman is in a pretrial detention center. She will remain there for a month and a half even though she has serious health problems.

Read the story of Sasha Skochilenko, an artist and musician from Petersburg, a former Bumaga staffer, and a person with a conscience.

The security services mounted a special operation to capture Sasha Skochilenko. An elderly woman informed on her.

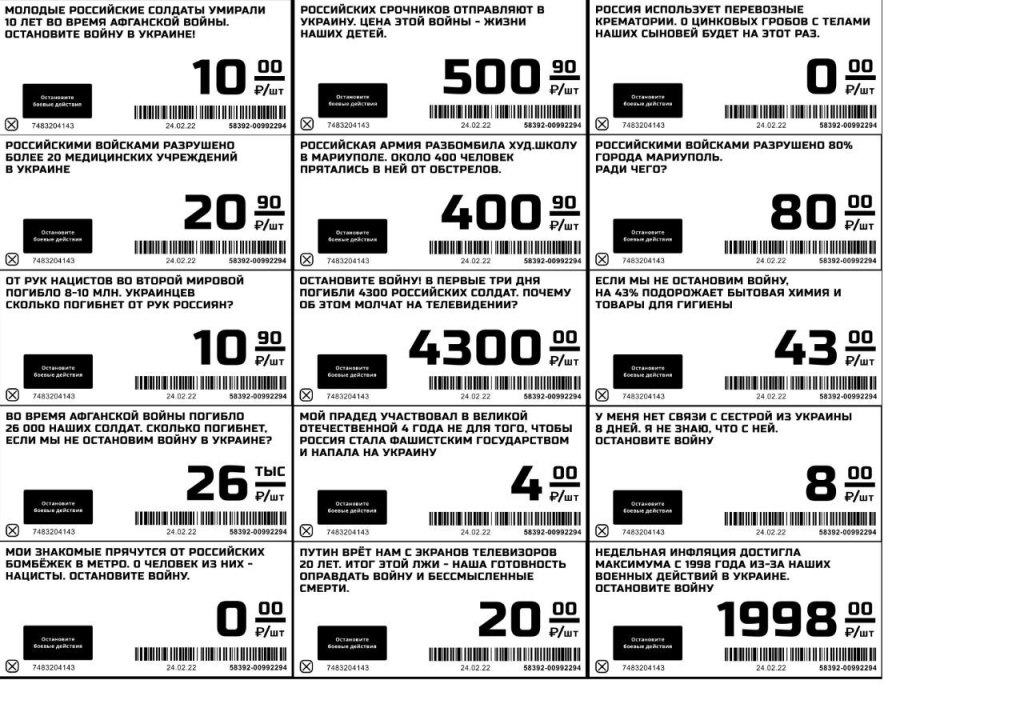

On the evening of March 31, anti-war messages were inserted into the shelf slots for price tags in the Perekrestok supermarket on the second floor of the Skipersky Mall on Vasilievsky Island.

According to two of Bumaga’s sources who are close to the investigation, the protest attracted the attention of a 75-year-old retired female shopper. According to one source, the woman went to the prosecutor’s office “to seek justice.” The second source says that she immediately went to the police.

Bumaga has learned that for over ten days, law enforcement officers, allegedly, interrogated Perekrestok employees and viewed security camera footage to determine who had replaced the price tags with the anti-war messages and where this person had gone after leaving the store.

On Monday morning, April 11, law enforcement officers conducted a special operation. They went to the apartment of the alleged suspect. His home is 900 meters away from Perekrestok. What exactly happened in the apartment is unknown. The man living there turned out to be a friend of 31-year-old Sasha Skochilenko.

That morning Sasha received a message from this friend saying that they were “looking for a body” in his apartment and asking her to come over. When she was already on her way, the friend texted her that “everything was okay.” Skochilenko’s friends believe that the security forces could have texted Sasha from her friend’s phone.

When Skochilenko arrived at the apartment, she was detained. It was around 11 a.m. Bumaga learned about her arrest at about 2 p.m. There was no news from Sasha for more than four hours, and law enforcement officials would not comment on the situation to Bumaga.

Later, Dmitry Gerasimov, Skochilenko’s lawyer, who is affiliated with the Net Freedoms Project, found out that Sasha’s apartment was being searched in her presence. She was then taken for questioning and kept in police custody until 12:30 a.m.

That same evening, Gerasimov told Bumaga that Sasha was the subject of a criminal investigation into disseminating “fake news about the Russian army” over the anti-war stickers with which she had switched the price tags at Perekrestok. According to investigators, the young woman had “publicly disseminated knowingly false information about the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.”

Skochilenko was charged under the second part of Russian Federal Criminal Code Article 207.3, which means that she faces up to ten years in prison. Investigators argue that she was “motivated by political hatred” when she distributed the flyers.

How the information on the anti-war flyers could be “knowingly false” and how Skochilenko came to be “motivated by political hatred” is not mentioned in the documents provided by the investigation.

The criminal case could have been opened due to a mention of those killed in Mariupol. But the contents of the stickers are unknown.

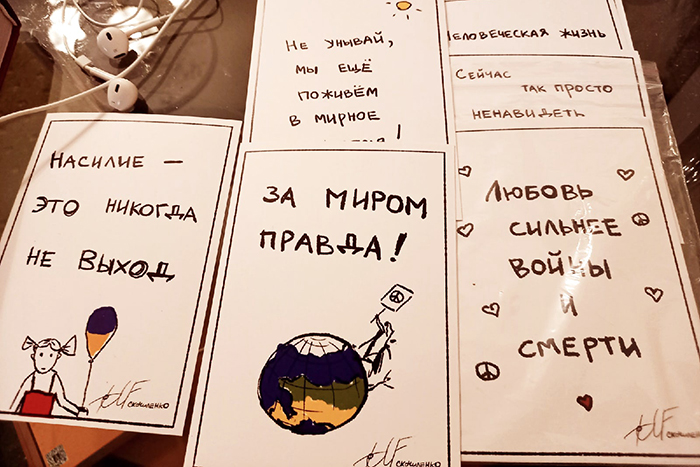

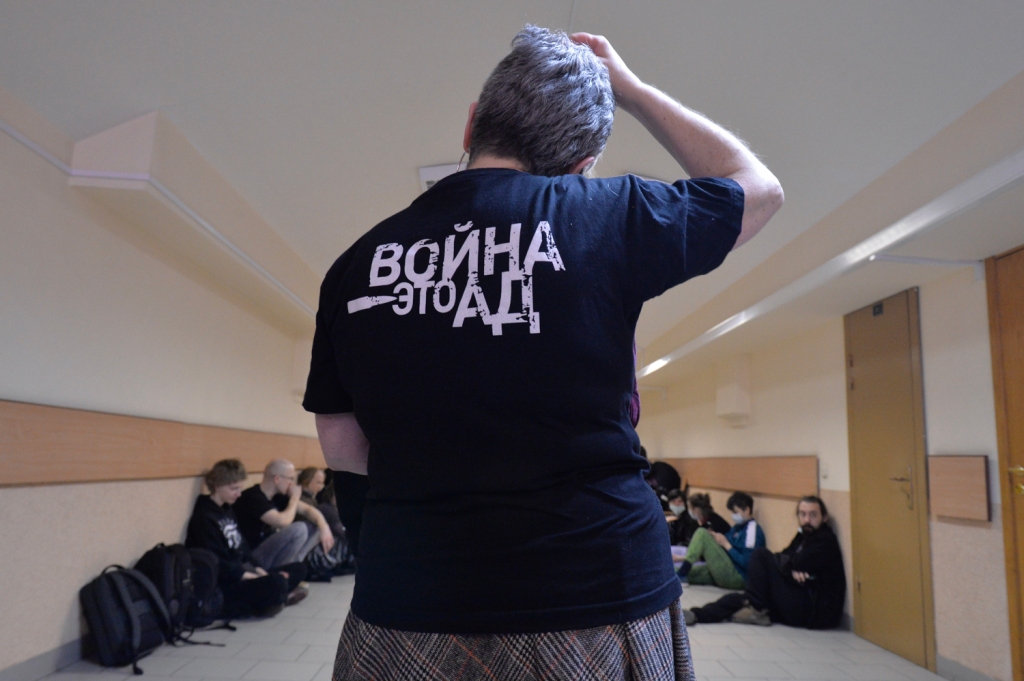

Sasha had been actively speaking out against the war in Ukraine since its very beginning. Along with the same friend whose apartment law enforcement officers raided, she had performed at intimate “Peace Jams” and also produced pacifist postcards. For this reason, the young woman’s acquaintances thought that she could have been charged with violating the recently popular article in the administrative offenses code for “discrediting” the Russian army. But that was not what happened.

Gerasimov tried to explain to Bumaga the rationale behind the investigation.

“[An administrative charge was not filed in Skochilenko’s case], because in those price tags [for which administrative proceedings had initiated] there were only statements against the war itself, while in Sasha’s case there was information about the alleged actions of the Russian Armed Forces,” he said.

At the same time, the part of the case file that the lawyer has reviewed does not mention the specific flyers for which Sasha was charged.

The Net Freedoms Project wrote that her case file contains price tags with information about the shelling of the theater in Mariupol and the deaths of civilians. Gerasimov told Bumaga that he could neither confirm nor deny this information, since “Sasha does not remember now what the price tags were and what was written on them.”

Earlier, Sasha had drawn anti-war stickers with such messages as “Don’t be discouraged, we’ll live in peacetime one day!” and “Human life has no price.”

“There are still so many people who do not know (do not remember?) what a miracle human life is, how beautiful and precious it is, and that violence is not the solution to problems,” Sasha said in explanation of her stance.

Currently, Sasha’s defense is based on her admission that she did plant anti-war flyers with information about Russia’s use of military force in Ukraine and its consequences in the store. But the young woman does not think that the information in the flyers was “false,” as the criminal code article that she was charged with stipulates, her lawyer said to Bumaga.

The judge sent Sasha Skochilenko to a pretrial detention center. She has celiac disease (gluten intolerance).

Sasha Skochilenko spent the night of April 12 in a temporary detention facility. As she later said in court, she managed to get some sleep there, but the guards did not give her water and did not bring her the food that friends had collected for her. Ultimately, the first hearing in Sasha’s case was postponed to the next day, and the young woman spent another twenty-four hours in the temporary detention facility.

Sasha’s bail hearing began at the Vasileostrovsky District Court at 9 a.m. on April 13. More than forty people had gathered at the court (where a Bumaga correspondent was present), including friends, journalists from both independent and pro-regime publications, activists, and human rights defenders.

Skochilenko was brought into court in handcuffs and placed in a cage. The young woman looked exhausted, and she asked for something to drink. There was no water in the courtroom, however, so the visitors looked for a water bottle among themselves. Despite her subdued spirits, Sasha thanked everyone who came.

“I did not anticipate so much support, that so many people would come [to the hearing],” Skochilenko said to Bumaga before the hearing began. “Everyone here tells me that you are doing something bad if you call for peace, but people’s support for me shows this is not the case. That is the most important thing.”

The judge in Sasha’s case was Elena Vladimirovna Leonova. Appointed to the Vasileostrovsky District Court by President Boris Yeltsin in 1998, she has held this post for over twenty years.

The media has mostly mentioned Judge Leonova in a positive light, and she was given high marks from the Petersburg qualification board of judges in the past. In particular, Leonova has often declined requests by prosecutors to jail activists and protestors, unlike her colleagues. There are also some ambiguous cases and decisions in her case history, however.

In the case of Sasha Skochilenko, the judge sided with the prosecution. Leonova began the trial by forbidding the taking of photographs in court. She then granted the prosecutor’s request to close the proceedings to the public because, allegedly, the state’s case was based on the interview records of witnesses. When members of the public were still present, the defense lawyer only managed to request the judge to release Skochilenko on bail, or prohibit her from certain actions, or at most, place her under house arrest.

The hearing, which took place behind closed doors, lasted almost five hours. When she delivered her ruling, Judge Leonova permitted several journalists, including the correspondent from Bumaga, to enter the courtroom. She began as follows: “It has been established that Skochilenko, acting deliberately, placed fragments of paper containing deliberately false information [about the actions of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation] in the premises of a trading hall.”

The judge read out the verdict quickly, not distinguishing between the arguments of investigators and her own words. “Misleading citizens about the actions carried out by the armed forces of the Russian Federation creates tension in society [and] conducts subversive activities [sic],” she said.

Among the arguments for Sasha’s being remanded in custody, Judge Leonova mentioned that Sasha:

- had been accused of committing a serious breach of public safety.

- “could exert pressure” (on investigators).

- refused to reveal the password to her telephone.

- “might destroy evidence” if she were at large.

- “has a sister in France.”

- “has friends in Ukraine.”

- “has the ability to hinder the collection of evidence and hide in Ukraine.”

- Is registered to reside in Petersburg but resides with a female acquaintance in a rented apartment, and the female friend does not have documents proving the residence’s lawfulness for serving as a place of house arrest, and the landlady might change her mind.

The judge emphasized that Skochilenko had “visited acquaintances in Ukraine.” In fact, a friend of hers told Bumaga, Sasha had gone to Ukraine in 2020 for work at a children’s camp, where she taught animation to the children.

Furthermore, Leonova brought up as an argument the fact that Skochilenko had “an administrative arrest for organizing a mass gathering of citizens during the pandemic.” Indeed, Sasha had been detained at an anti-war protest on March 3, her friend told Bumaga. Skochilenko was released after a night in the police station, and a court sentenced her to a fine of ten thousand rubles. Sasha had challenged the decision, but on appeal the court upheld the verdict.

The judge did not consider the fact that the artist had been diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder and celiac disease, a genetic gluten intolerance requiring a strict diet, to be a valid reason for declining to send Sasha to a pretrial detention center.

Leonova noted separately that Skochilenko had not been diagnosed with serious illnesses and that there was no evidence that she needed emergency medical care. When the defense lawyer provided the court with a doctor’s note about Sasha’s health, the judge stated that the document could not be accepted because it did not mention the source of the information.

Judge Leonova ultimately decided to remand Sasha in custody to Pretrial Detention Center No. 5 until May 31. In response, the people in the courtroom cried and told Sasha that everything would be okay, while people in the hallway shouted, “Shame on you!” to the judge. As people left the courtroom, Skochilenko smiled and waved to her friends.

“The war will end, and I will be amnestied,” Sasha managed to tell a friend before the bailiffs forced him to leave the courtroom.

Sasha is an artist and a musician. She wrote A Book on Depression and filmed protest rallies for Bumaga. Many people support her, but they are pessimistic.

“Sasha is one of my most talented acquaintances,” journalist Arseniy Vesnin, a friend of Skochilenko’s, told Bumaga. “We met around fifteen years ago. We used to play Mind Games—it was this project on Channel 5 where schoolchildren would debate. Sasha was always—or rather she is (we’re almost talking like obituaries now)—very smart, talented, and well-read.”

Sasha was born on September 13, 1990, in Leningrad. At the age of seventeen she enrolled at the Theater Academy to study directing but withdrew during her final year, transferring to St. Petersburg State University’s Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences where she studied anthropology and graduated with honors.

From 2013-2015, Sasha made video reports of rallies and protests for Bumaga.

“Sasha is the ‘good person’ from Andrei Platonov’s works,” says Kirill Artemenko, general director of Bumaga. “Platonov’s heroes do good without fully realizing that they are good, without expecting kindness from anyone and without being offended by evil. They are hardworking, patient people. They might look weak, but in reality, they are very strong. Their strength is in their principles and natural, effortless kindness.”

When Sasha fell ill with cyclothymia, a milder form of bipolar affective disorder, she wrote A Book on Depression to support people with similar health problems. The book has been translated into English and Ukrainian. The story of Sasha’s struggle with her illness can be read in this text, published by Bumaga.

Lately, Sasha had been filming and editing lectures for the feminist space Eve’s Ribs and helping to renovate the homes of women who did not want to hire a handyman to do the work, a friend tells Bumaga. She also worked as an administrator at a children’s center on Vasilievsky Island. “She communicates well with children, unlike with the cops,” explains the interviewee.

According to the friend, Skochilenko never had the goal of building a career. It was important to her to do good while also being able to live on the money she earned.

“I don’t have any kind of particular profession. In different interviews they have called me an artist from Petersburg, a cartoonist, and an actress, and many other things,” Sasha, who at that moment was working as a nanny, said in 2020. “I don’t want to have a particular profession. And in fact, I don’t have one.”

Sasha’s passion has always been music, her friends say. Sasha views it as “an instrument of freedom,” said Skochilenko’s friend Alexei Belozerov. “She wants to create a free space with the help of music—without the hierarchies that inevitably arise within a musical collective, without the division between performers and listeners,” says Alexei.

Photo by Andrei Bok for Bumaga

A friend of Sasha who has been involved with her in musical events on many occasions said that the main idea of her music is free improvisation, so that “people who don’t have a musical education but very much want to play won’t be afraid to grab an instrument and play together.” For example, the friend said, Sasha held music jams at psychoneurological resident treatment facilities as a form of art therapy.

Sasha vigorously advocated the idea of freedom even after February 24. “I do not support the war in Ukraine! I went on the streets today to say it out loud!” she wrote from a rally on the first day of the war. “Two years ago, I taught children in Ukraine at a children’s camp to film videos. I remember each of their faces. They are no different from Russian children.”

Sasha decided not to emigrate, despite the risks. “Sasha said that she would not leave, because she has her social capital here, Petersburg is her city, and Russian is her language,” Sasha’s friend Arseny tells Bumaga. “She is not someone who made it her goal to fight the regime. She is a person with a conscience, and as a person with a conscience, she could not help but react to this shameless situation that is now happening in Russia”.

Guarantees for Skochilenko were signed by St. Petersburg Legislative Assembly deputies Boris Vishnevsky and Mikhail Amosov, [Pskov] politician Lev Schlosberg, and municipal deputy Sergei Troshin. The court also received a positive character reference from Bumaga general director Kirill Artemenko. There are hundreds of posts on social networks about her case, which has been dubbed absurd. The case has also been covered by Russia’s remaining independent media. And Bumaga has learned that protests in support of Sasha have been organized in London.

The main source of public indignation is not even that Sasha is being prosecuted for an anti-war position, but, rather, the possible sentence (up to ten years in a penal colony) and the fact that she was sent to a pretrial detention center despite her illness.

“I remind you that no one was punished for threats to ‘cut off heads,’” wrote Vishnevsky. “And there was no response to two attempts to kill my friend Vladimir Kara-Murza. But for anti-war speeches, [people get sent to] a pre-trial detention center, and then to a penal colony for ten years. Feel the difference.”

Many of those who spoke with Bumaga and who advocate for Sasha’s release are pessimistic. For example, Vishnevsky himself told Bumaga that he would be glad to be proved wrong if the outcome of the case were positive after all. Journalist Arseny Vesnin recalls that it was clear to him that Sasha would be sent to a pretrial detention center, although he did not want to believe it.

“We must pray that not only the war ends, but also that something in our country changes. This would be a good outcome. But realistically I don’t see any good outcomes,” Vesnin concludes.

Sasha’s friend, who vigorously advocates for her release, tells Bumaga that he cannot express his opinion about what is happening, including in this case, without breaking the law.

“This is terror,” he says anonymously. “It has been unleashed in the original sense of the word— as ‘fear’ and ‘horror.’ They are maintaining an atmosphere of terror. This is the only way to explain why, for replacing one piece of paper in a store with another, a bunch of people in uniform write up interrogation reports and put them into case files, conduct searches, and arrange an ambush using the person’s friend. In this sense, the possible outcome of this case is the same as that of everything that is happening here. The terror will grow, the terror will intensify. They will be trying to frighten us and to break us more and more.”

Sasha’s case is not an exception. The security forces are persecuting many people who have protested the war by replacing price tags.

As of April 7, four days before Sasha Skochilenko’s arrest, twenty-one criminal cases had been launched nationwide on suspicions of spreading “fake news about the Russian army,” wrote human rights lawyer Pavel Chikov. Almost all of the cases involve publishing “knowingly false information” on the internet—with the exception of five cases, and only one of those cases also involves distributing flyers in a store.

Despite increased pressure, Russians continue to replace price tags with anti-war messages. This “quiet protest” is considered an easy way to convey the truth about what is happening in Ukraine to people living in a different “information bubble.”

Replacing price tags in stores became a popular form of protest after the campaign was announced by Feminist Anti-War Resistance, a movement of Russian feminists that came to life in February 2022 in response to the war. But the movement recognizes that protesting can be dangerous.

Courtesy of Kholod. This image was not included in the original article, in Russian, on Bumaga.

“The police have increasingly been tracking down people involved in various types of anti-war protest,” a spokeswoman for Feminist Anti-War Resistance told Bumaga. “To date, we know that one of our participants, who put anti-war slogans on price tags, was tracked down through the card she used to pay in the store.”

The movement says that they have not been in contact with Skochilenko—or, perhaps, do not know that they have had contact with her, since they communicate with many members of the movement anonymously. But they expressed their support for the artist: “We believe that Sasha should be released immediately, and the case against her should be closed and all charges dropped.”

“Today, anti-war price tags are one of the most common forms of protest, along with posting stickers and flyers in public places,” the spokeswoman said. “Unfortunately, no forms of anti-war protest are absolutely safe in Russia today. We believe it is important to emphasize this regularly and encourage everyone to pay special attention to safety rules and to take potential risks into account.”

Two days after the hearing, Sasha Skochilenko is still in the temporary detention facility. In the evening, she is supposed to be taken to the pretrial detention center. She delivered a message through her lawyer, saying that she was doing well and was grateful for people’s support.

The wardens at the temporary detention facility promised to provide Sasha with a gluten-free diet and, according to her lawyer, they have kept their promise. A request to meet her dietary needs has also been sent to the pretrial detention center. At the same time, Sasha’s girlfriend has been summoned to the Investigative Committee for questioning.

Bumaga will continue covering the case of Sasha Skochilenko. For the latest news, subscribe to our Telegram channel and the Free Sasha Skochilenko support group channel on Telegram. You can also sign a petition calling for Sasha’s release.

Source: Bumaga, 15 April 2022. Translated by Christopher Damon, Zhenia Dubrova, Savannah Eller, Emily Hester, Marta Hulievska, Kirill Lanski, Jasmine Li, Milla McCaghren, and Andres Meraz. Thanks to Victoria Somoff for her assistance and the Fabulous AM for her abiding support of this project. ||| TRR

Discover more from The Russian Reader

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

4 thoughts on “The Case of Sasha Skochilenko”