A so-called Cossack lashes protesters with a plaited whip (nagaika) at the He’s No Tsar to Us opposition protest rally at Pushkin Square in Moscow on May 5, 2018. Photo by Ilya Varlamov

A so-called Cossack lashes protesters with a plaited whip (nagaika) at the He’s No Tsar to Us opposition protest rally at Pushkin Square in Moscow on May 5, 2018. Photo by Ilya Varlamov

Сossacks Were Not Part of the Plan: Men with Whips Take Offense at the Opposition

Alexander Chernykh

Kommersant

May 8, 2017

The Presidential Human Rights Council (PHRC) plans to find out who the Cossacks were who scuffled with supporters of Alexei Navalny during the unauthorized protest rally on May 5 in Moscow. Meanwhile, the Moscow mayor’s office and the Central Cossack Host claimed they had nothing to do with the Cossacks who attempted to disperse opposition protesters. Kommersant was able to talk with Cossack Vasily Yashchikov, who admitted he was involved in the tussle, but claimed it was provoked by Mr. Navalny’s followers. Human rights defenders reported more than a dozen victims of the Cossacks have filed complaints.

The PHRC plans to ask law enforcement agencies to find out how the massive brawl erupted during the unauthorized protest rally on May 5 in Moscow. PHRC chair Mikhail Fedotov said “circumstances were exacerbated” when Cossacks and activists of the National Liberation Front (NOD) appeared at the opposition rally.

“It led to scenes of violence. We must understand why they were they and who these people were,” said Mr. Fedotov.

“Our main conclusion has not changed: the best means of counteracting unauthorized protest rallies is authorizing them,” he added.

On May 5, unauthorized protest rallies, entitled He’s No Tsar to Us, called for by Alexei Navalny, took place in a number of Russian cities. In Moscow, organizers had applied for a permit to march down Tverskaya Street, but the mayor’s officers suggested moving the march to Sakharov Avenue. Mr. Navalny still called on his supporters to gather at Pushkin Square, where they first engaged in a brawl with NOD activists and persons unknown dressed in Cossack uniforms. Numerous protesters were subsequently detained by regular police. Approximately 700 people were detained in total.

The appearance on Pushkin Square of Cossacks armed with whips has provoked a broad response in Russia and abroad. The Guardian wrote at length about the incident, reminding its readers that Cossacks would be employed as security guards during the upcoming 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia. The Bell discovered a Central Cossack Host patch on the uniform of one of the Cossacks photographed during the brawl. According to the Bell, which cites documents from the Moscow mayor’s office, the Central Cossack Host was paid a total of ₽15.9 million for “providing security during large-scale events.”

However, Vladimir Chernikov, head of the Moscow Department of Regional Security, stressed, during an interview with Kommersant FM, that on May 5 “no Cossacks or any other organization were part of the plan and the means of providing security.”

Chernikov said police and the Russian National Guard acted impeccably. Spokesmen for the Central Cossack Host also said they had not dispatched any Cossacks to guard Pushkin Square, and that the Cossacks who, wearing their patches, did go to the square, had “voiced their civic stance.”

Bloggers have published information about the Cossacks they have been able to identify from photos and video footage of the rally. One video depicts a bearded man who grabs a placard, bearing the slogan “Open your eyes, you’re the tsar’s slave!”, from a young oppositionist before arguing with Open Russia coordinator Andrei Pivovarov. The Telegram channel BewareOfThem reported the man was Vasily Yashchikov, member of the Union of Donbass Volunteers. Mr. Yashchikov has confirmed to Kommersant he was, in fact, at the rally and was involved in the brawl with opposition protesters. Yet, he claimed, most of the Cossacks at Pushkin Square had nothing to do with the Central Cossack Host, as claimed by the Bell. According to Mr. Yashchikov, the brawlers mainly consisted of nonregistered (i.e., unaffiliated with the Russian government) Cossacks from two grassroots organizations, the First Hundred and the Crimean Regiment. Moreover, they allegedly showed up at the rally independently of one another.

“The rally was discussed in Cossack groups, and someone suggested we go and talk to people,” Mr. Yashchikov told Kommersant. “We have nearly a hundred people in the Hundred, but only fifteen decided to go. At the square, we met Cossacks from the Crimean Regiment, which is actually not Crimean, but from the Moscow Region. But our organizations are not friendly, so we were there separately.”

He admitted there were several people from the Central Cossack Host at Pushkin Square, but his group did not interact with them, either.

So-called Cossacks at the He’s No Tsar to Us opposition rally at Pushkin Square, Moscow, May 5, 2018. Photo by Alexander Miridonov. Courtesy of Kommersant

So-called Cossacks at the He’s No Tsar to Us opposition rally at Pushkin Square, Moscow, May 5, 2018. Photo by Alexander Miridonov. Courtesy of Kommersant

According to Mr. Yashchikov, the Cossacks came to Pushkin Square to talk with Mr. Navalny’s supporters, but had no intention of being involved in dispersing the rally.

“There were one and half thousand people there [the Moscow police counted the same number of protesters—Kommersant]. There were thirty-five of us at most, and we had only two whips. You could not have paid us to wade into that crowd,” claimed Mr. Yashchikov.

Mr. Yashchikov claimed he managed to have a friendly chat with Mr. Navalny, but opposition protesters were aggressive, he alleged.

“Someone picked on us, asking why we had come there, that it was their city. Another person tried to knock my cap off, while they swore at other Cossacks and blasphemed the Orthodox faith,” Mr. Yashchikov complained. “Well, we couldn’t take it anymore.”

People who attended the rally have denied his claims.

“The Cossacks acted cohesively, like a single team,” said Darya, who was at the rally [Kommersant has not published her surname, as she is a minor]. “They formed a chain and started pushing us towards the riot police, apparently, to make their job easier. The Cossacks kicked me, while they encircled my boyfriend and beat him. They retreated only when they realized they were being film and photographed.”

Darya planned to file a complaint with the police charging the Cossacks with causing her bodily harm. Currently, human rights defenders from Agora, Zona Prava, and Public Verdict have documented more than fifteen assault complaints filed against the Cossacks.

Oppositionists have claimed the police mainly detained protesters, allegedly paying almost no attention to the Cossacks and NOD activists. Kirill Grigoriev, an Open Russia activist detained at the rally, recounted that, at the police station where he was taken after he was detained, he pretended to be a NOD member, and he was released by police without their filing an incident report.

“When we arrived at the Alexeyevsky Police Precinct, a policeman immediately asked who of us was from NOD. I jokingly pointed at myself. He took me into a hallway and asked me to write down the surnames of other members of the organization,” said Mr. Grigoriev.

He wrote down the surnames of ten people, after which everyone on the list was given back their internal Russian passports and released.

*********

Cossacks Confront Navalny Supporters for First Time

Regime Prepares for Fresh Protests, Including Non-Political Ones, Analysts Argue

Yelena Mukhametshina and Alexei Nikolsky

Vedomosti

May 6, 2018

He’s No Tsar to Us, the unauthorized protest rally in Moscow held by Alexei Navalny’s supporters, differed from previous such rallies. On Tverskaya Street, provocateurs demanded journalists surrender their cameras. By 2:00 p.m., the monument to Pushkin was surrounded by activists of the National Liberation Front (NOD). When protesters chanted, “Down with the tsar!” they yelled “Maidan shall not pass!” in reply. Behind the monument were groups of Cossacks, who had never attended such rallies. In addition, for the first time, the police warned people they intended to use riot control weapons and physical force, and indeed the actions of the security forces were unprecedentedly rough. The riot police (OMON) detained protesters by the hundreds, and Cossacks lashed them with plaited whips.

The Moscow police counted 1,500 protesters at the rally, while organizers failed to provide their own count of the number of attendees. Navalny said the nationwide rallies were a success. His close associate Leonid Volkov argued that “in terms of numbers, content, and fighting spirit, records were broken,” also noting the police’s unprecedented brutality. According to OVD Info, around 700 people were detained in Moscow, and nearly 1,600 people in 27 cities nationwide. Citing the PHRC, TASS reported that 658 people were detained in Moscow.

“He’s No Tsar to Us, May 5: A Map of Arrests. 1,597 people were detained during protest rallies on May 5, 2018, in 27 Russian cities, according to OVD Info. According to human right activists, during nationwide anti-corruption protests on March 26, 2017, more than 1,500 people were detained. Source: OVD Info.” Courtesy of Vedomosti

PHRC member Maxim Shevchenko demanded the council be urgently convoked due to “the regime’s use of Black Hundreds and fascist militants.” According to a police spokesman, the appearance at the rally of “members of different social groups” was not engineered by the police, while the warning that police would use special riot control weapons was, apparently, dictated by the choice of tactics and the desire to avoid the adverse consequences of the use of tear gas.

According to NOD’s leader, MP Yevgeny Fyodorov, 1,000 members of the movement were involved in Saturday’s rally.

“We wanted to meet and discuss the fact the president must be able to implement his reforms. Because we have been talking about de-offshorization and withdrawing from a unipolar world for five years running, but things have not budged an inch,” said Fyodorov.

NOD did not vet their actions with the Kremlin, the leadership of the State Duma or the Moscow mayor’s office, Fyodorov assured reporters.

On Sunday, the Telegram channel Miracles of OSINT reported that, in 2016–2018, the Central Cossack Host, whose members were at the rally, received three contracts worth nearly ₽16 million from the Moscow Department for Ethnic Policy for training in the enforcement of order at public events. As Vedomosti has learned, according to the government procurement website, the Central Cossack Host received eleven contracts, worth nearly ₽38 million, from the Moscow mayor’s office over the same period.

Gleb Kuznetsov, head of the Social Research Expert Institute (EISI), which has ties to the Kremlin, argued there was no brutality at the rally.

“In Paris, the scale of protests is currently an order of magnitude higher, but no one speaks about their particular brutality. In Russia, so far the confrontation has been cute, moderate, and provincial. The only strange thing is that, in Russia, people who are involved in such protests, which are aimed at maximum mutual violence, are regarded as children. But this is not so. Everything conformed to the rules of the game, common to the whole world. If you jump a policeman, don’t be surprised if he responds with his truncheon,” said Kuznetsov.*

The Russian government has allied itself with the Cossacks and NOD, which are essentially illegal armed formations, argued Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Moscow Carnegie Center.

“This does not bode well. Apparently, in the future, such formations will be used to crack down on protests,” said Kolesnikov.

The authorities are preparing for the eventuality there will be more protests. Even now the occasions for them have become more diverse, and they are spreading geographically, noted Kolesnikov.

Grassroots activism has been growing, and the authorities have realized this, political scientist Mikhail Vinogradov concurred. They are always nervous before inaugurations. In 2012, there was fear of a virtual Maidan, while now the example of Armenia is fresh in everyone’s minds, he said.

“The security services had to flex their muscles before the new cabinet was appointed. Although, in view of the upcoming FIFA World Cup, law enforcement hung the regime out to dry contentwise,” said Vinogradov.

* In September 2017, the Bell reported that state corporations Rosatom and RusHydro were financing EISI to the tune of ₽400 million each, and it could not be ruled out that the so-called social research institute was receiving subsidies from other state companies.

Translated by the Russian Reader

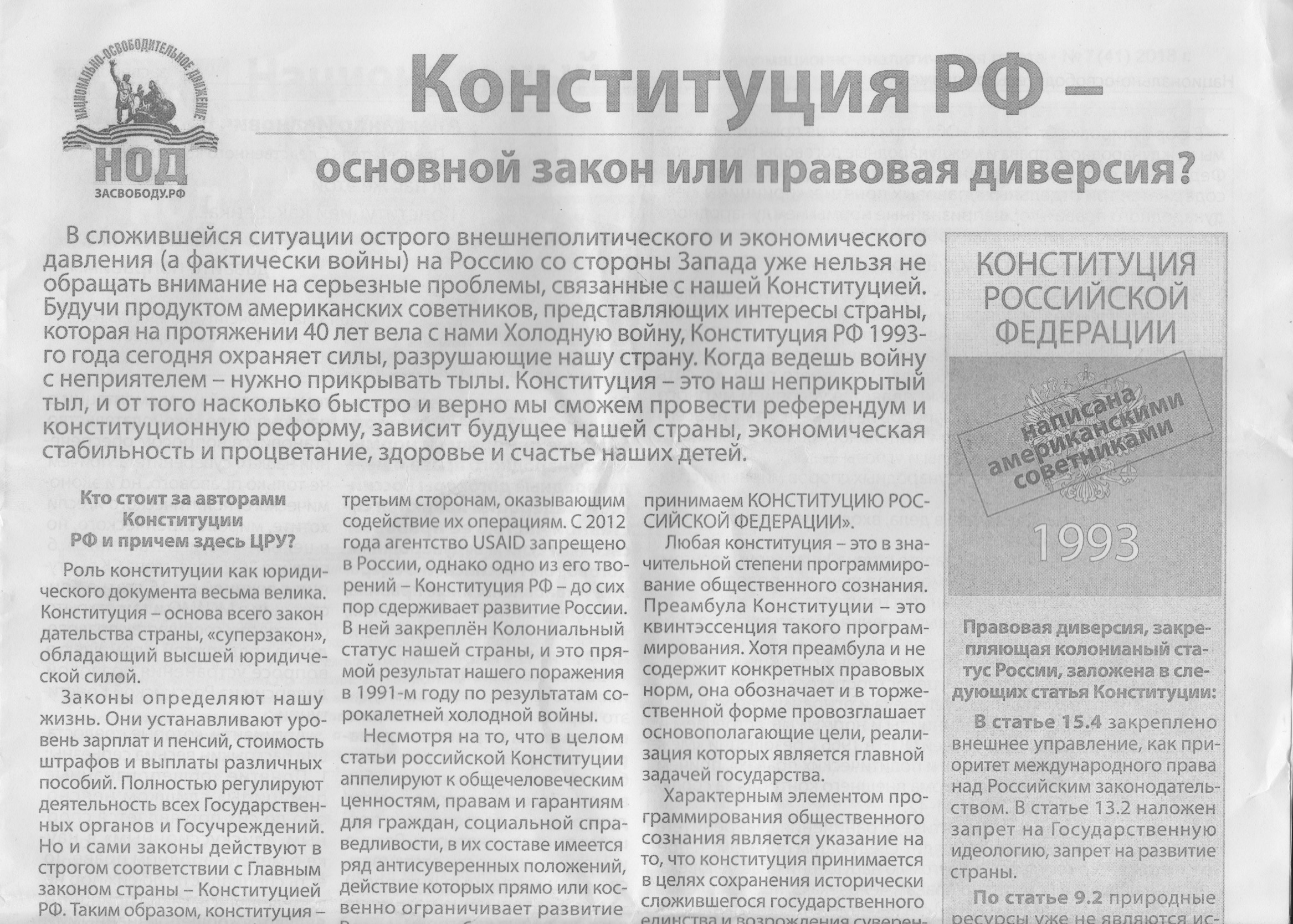

“The Russian Constitution: The Basic Law or Legal Sabotage?” Front page of a newspaper handed out on the streets of Petersburg by memberx of

“The Russian Constitution: The Basic Law or Legal Sabotage?” Front page of a newspaper handed out on the streets of Petersburg by memberx of  Petersburg democracy activist Pavel Chuprunov, holding a placard that reads, “‘Yes, we tasered them, but it wasn’t torture. We were doing our jobs!’ Admission by the

Petersburg democracy activist Pavel Chuprunov, holding a placard that reads, “‘Yes, we tasered them, but it wasn’t torture. We were doing our jobs!’ Admission by the  A so-called Cossack lashes protesters with a plaited whip (nagaika) at the He’s No Tsar to Us opposition protest rally at Pushkin Square in Moscow on May 5, 2018. Photo by

A so-called Cossack lashes protesters with a plaited whip (nagaika) at the He’s No Tsar to Us opposition protest rally at Pushkin Square in Moscow on May 5, 2018. Photo by  So-called Cossacks at the He’s No Tsar to Us opposition rally at Pushkin Square, Moscow, May 5, 2018. Photo by Alexander Miridonov. Courtesy of Kommersant

So-called Cossacks at the He’s No Tsar to Us opposition rally at Pushkin Square, Moscow, May 5, 2018. Photo by Alexander Miridonov. Courtesy of Kommersant