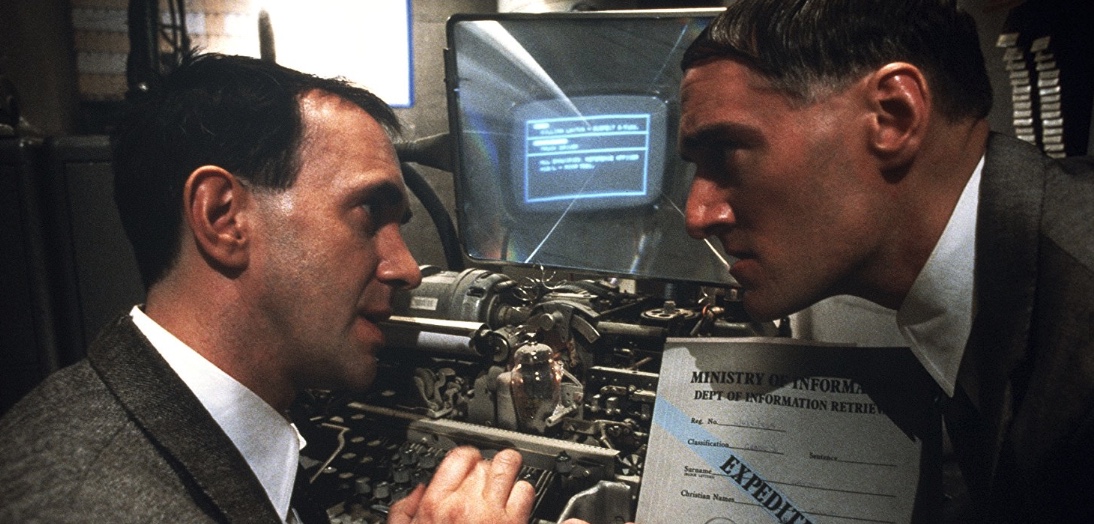

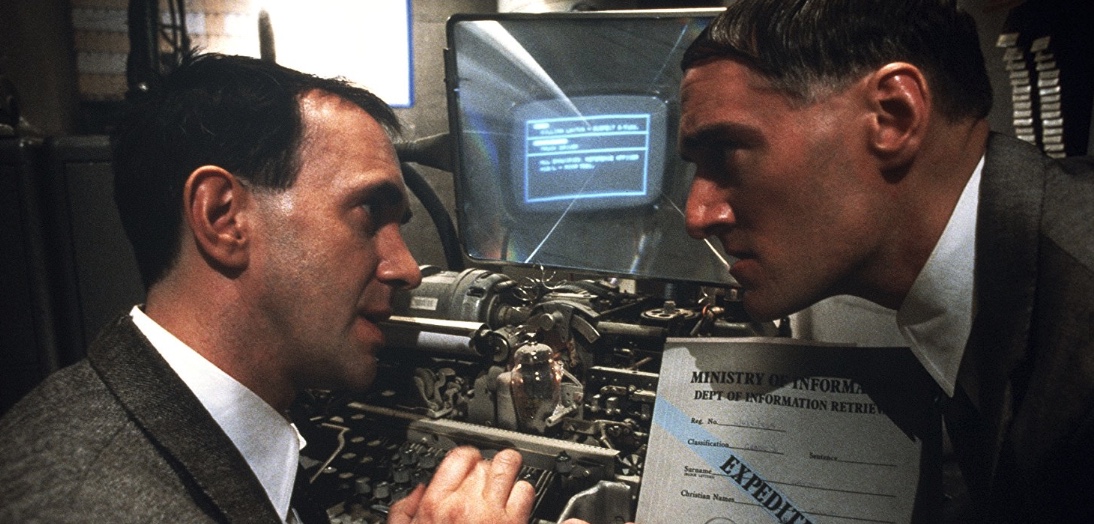

Jonathan Pryce and Terry McKeown in Brazil (1985). Courtesy of imdb.com

Jonathan Pryce and Terry McKeown in Brazil (1985). Courtesy of imdb.com

Authorized to Remain Silent

Why We Know Nothing about the Outcome of Most Criminal Cases and Verdicts against People Who, According to the Russian Secret Services, Planned or Attempted to Carry Out Terrorist Attacks

Alexandra Taranova

Novaya Gazeta

April 27, 2018

High-ranking officials from the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), the Russian Interior Ministry (MVD), and the Russian National Anti-Terrorist Committee (NAK) regularly report on the effective measures against terrorism undertaken by their agencies. If we add reports of constant counter-terrorist operations in the North Caucasus, especially in Dagestan and Chechnya, operations involving shootouts and the storming of houses, we might get the impression the level of terrorism in Russia is close to critical, resembling the circumstances somewhere in Afghanistan, the only difference being that Afghanistan does not have the FSB, the MVD, and the NAK to protect it.

Over the past two weeks, there were at least two such stories in the news.

A few days ago, the FSB reported it had “impeded the criminal activity of supporters of the international terrorist organization Islamic State, who […] had begun planning high-profile terrorist attacks using firearms and improvised explosive devices.”

The FSB’s Public Relations Office specified the terrorist attacks were to be carried out in goverment buildings in Stavropol Territory.

Earlier, TASS, citing the FSB’s Public Relations Office, reported that, since the beginning of the 2018, six terrorist attacks had been prevented (including attacks in Ufa, Saratov, and Ingushetia), while three crimes of a terrorist nature had been committed (in Khabarovsk Territory, Dagestan, and Sakhalin Region), and this had been discussed at a meeting of the NAK. Other media outlets quoted FSB director Alexander Bortnikov, who claimed that last year the security services had prevented twenty-five terrorist attacks, but four attacks, alas, had gone ahead.

For the most part, however, it is impossible to verify these reports, because, with rare exceptions, the terrorists, either potential terrorists or those who, allegedly, carried out terrorist attacks, are identified by name. Neither the Russian Investigative Committee (SKR) nor the FSB informs Russians about subsequent investigations, about whether all the terrorists and their accomplices have been rounded up. Likewise, with rare exceptions, we know nothing either about court trials or verdicts handed down in those trials.

Novaya Gazeta monitored reports about prevented terrorist attacks from November 2015 to November 2017. We analyzed all the media publications on this score: the outcome of our analysis has been summarized in the table, below. The veil of secrecy makes it extremely hard to figure out what reports merely repeat each other, that is, what reports relate to one and the same events, and we have thus arrived at an overall figure for the number of such reports. Subsequently, by using media reports and court sentencing databases, we have counted the number of cases that officially resulted in court sentences.

Most news reports about prevented terrorist attacks in Russia are not followed up. For example, at one point it was reported (see below) that five people with ties to Islamic State had been apprehended in Moscow and Ingushetia for planning terrorist attacks, and this same news report mentioned that a criminal case had been launched. But only the surname of the alleged band’s leader was identified, and he was supposedly killed while he was apprehended. There is no more information about the case. Over a year later, we have no idea how the investigation ended, whether the case went to trial, and whether the trial resulted in convictions and verdicts.

Other trends also emerged.

During the two-year period we monitored, reports about prevented terrorist attacks and apprehended terrorists encompassed a particular group of Russian regions: Moscow, Crimea, Petersburg, Kazan, Rostov, Baskortostan, Volgograd, Yekaterinburg, and Krasnoyarsk. When we turn to verdicts handed down in such cases, this list narrows even further. Rostov leads the country, followed by Crimea. There are two reports each from Krasnoyarsk and Kazan, and several isolated incidents. The largest number of news reports about terrorist attacks and acts of sabotage, i.e., 30% of all the reports we compiled and analyzed, originated in Crimea.

| |

FSB |

MVD |

NAK |

Russian Security Council (Sovbez) |

| Number of reports of prevented terrorists, November 2015–November 2017 |

3,505 reports (18,560 identical reports in the media) |

1,702 reports

(3,571 identical reports in the media) |

492 reports

(852 identical reports in the media) |

236 reports

(1,122 identical reports in the media) |

| Outcomes: arrests, criminal charges, verdicts, etc. |

13 verdicts,

14 arrests |

3 verdicts,

2 arrests |

2 incidents: in one case, it was reported that all the detainees had been killed; in the other, that the detainees awaited trial, but were not identified by name. |

It is impossible to find out what happened to any detainees, since no information was provided about them. The exception is Lenur Islyamov, who is currently at large and vigorously pursuing his objectives. |

The Triumps of the Special Services with No Follow-Up

Here are the most revealing examples.

On November 12, 2016, RBC reported the security services had apprehended a group of ten terrorists, migrants from Central Asia. According to the FSB, they planned “high-profile terrorist attacks” in heavily congested areas of Moscow and Petersburg. Officials confiscated four homemade bombs, firearms, ammunition, and communications devices from the militants. The FSB claimed all the detainees had confessed to their crimes.

In the same news report, the FSB was quoted as having reported that on October 23, 2016 “there occurred an attack on police officers, during which two alleged terrorists were shot dead” in Nizhny Novgorod. The report stressed that, three days later, the banned group ISIL claimed responsibility for the attack, just as it had taken responsibility for an attack on a traffic police post in Moscow Region on August 18, 2016.

There were no names and no details. The outcomes of the investigations, the plight of the detainees, and judicial rulings were never made public, nor did state investigators or defense counsel share any information.

This same RBC article mentions that, four days before the alleged incident in Nizhny Novgorod, the SKR had reported the apprehension of an ISIL supporter who had been planning a terrorist attack at a factory in Kazan, while Interfax‘s sources reported the apprehension of a man who had been planning a terrorist attack in Samara. It was also reported that in early May 2016 the FSB had reported the apprehension of Russian nationals in Krasnoyarsk who were “linked to international terrorist organizations and had planned a terrorist attack during the May holidays.”

No names were mentioned at the time. Later, however, details of the case were made public.

Thus, on April 7, 2017, Tatar Inform News Agency reported that the Volga District Military Court in Kazan had handed down a verdict in the case of Robert Sakhiyev. He was found guilty of attempting to establish a terrorist cell in Kazan. The first report that a terrorist attack had been planned at an aviation plant in Kazan was supplied by Artyom Khokhorin, Interior Minister of Tatarstan, during a meeting of MVD heads. According to police investigators, Sakhiyev had been in close contact with a certain Sukhrob Baltabayev, who was allegedly on the international wanted list for involvement in an illegal armed group. Using a smartphone, Sakhiyev had supposedly studied the plant’s layout via a satellite image.

On August 2, 2017, RIA Novosti reported that a visting collegium of judges from the Far East District Military Court in Krasnoyarsk had sentenced Zh.Zh. Mirzayev, M.M. Abdullayev, and Zh.A. Abdusamatov for planning a terrorist attack in Krasnoyarsk in May 2016 during Victory Day celebrations. Mirzayev was sentenced to 18 years in prison; Abdullayev, to 11 years in prison; and Abdusamatov, to 11 years in a maximum security penal colony. According to investigators, Mirzayev worked as a shuttle bus driver in Krasnoyarsk and maintained contact with Islamic State via the internet. Mirzayev decided to carry out a terrorist attack by blowing up a shuttle bus.

On January 26, 2017, TASS reported the police and FSB had identified a group of eight people planning terrorist attacks in Moscow in the run-up to State Duma elections. Oleg Baranov, chief of the Moscow police, had reported on the incident at an expanded collegium of the MVD’s Main Moscow Directorate.

We know nothing more about what happened to the “identified” would-be terrorists.

On January 31, 2017, RBC issued a bulletin that the Russian secret services had prevented an attempt to carry out terrorist attacks in Moscow during the 2016 Ice Hockey World Championships. The source of the news was Igor Kulyagin, deputy head of staff at the NAK. The militants were allegedly detained on May 2.

“We succeed in catching them as a result of a vigorous investigative and search operation in the city of Moscow,” the FSB added.

The names of the militants were not reported nor was there any news about an investigation and trial.

In the same news item, Mr. Kulyagin is quoted as saying, “In total, Russian special services prevented around [sic] 40 terrorist attacks, liquidated [sic] about [sic] 140 militants and 24 underground leaders, and apprehended about [sic] 900 people in 2016.”

According to Mr. Kulyagin, in Ingushetia on November 14, 2016, the authorities uncovered five militants who “had been planning terrorist attacks in crowded places during the New Year’s holidays, including near the French Embassy in Moscow.”

Again, the reading public was not provided with any names or information about the progress of the investigation. The only alleged terrorist who was identified was Rustam Aselderov, who had been murdered.

“According to the special services, [Aselderov] was involved in terrorist attacks in Volgograd in 2013 and Makhachkala in 2011.”

We have no idea whether an official investigation of his murder was ever carried out.

Lenta.Ru reported on February 1, 2017, that FSB officers in Krasnodar Territory had prevented a terrorist attack. The supposed terrorists had planned an explosion at New Year’s celebrations. A possible perpetrator of the terrorist attack, a 38-year-old native of a Northern Caucasus republic, was apprehended. No other particulars of the incident were reported, and they still have not been made public to this day.

On October 2, 2017, Russia Today, citing the FSB, reported an IS cell had been apprehended in Moscow Region. Its members has allegedly planned to carry out “high-profile terrorist attacks” in crowded places, including public transport. The FSB added that foreign emissaries had led the cell, whose members had included Russian nationals.

No names or details were subsequently provided to the public.

The same article reported that, on August 31, 2017, the FSB had apprehended two migrants from Central Asia, who had been planning terrorist attacks in congested places in Moscow and Moscow Region on September 1. RIA Novosti reported the same “news” in August 2017. The detainees were, allegedly, members of IS.

According to the FSB, one of the men had “planned to attack people with knives.” His comrade had planned to become a suicide bomber and blow himself up in a crowd. Supposedly, he had made a confession.

We know nothing about what happened to the two men and the criminal case against them.

On November 7, 2017, Izvestia reported MVD head Vladimir Kolokoltsev’s claim that a Kyrgyzstani national had been apprehended in the Moscow Region town of Khimki. The man had, allegedly, been planning to carry out a terrorist attack outside a subway station using a KamAZ truck. The detained man was not identified. We know nothing about what has happened to him or whether the investigation of the case has been completed.

Trials of Terrorists

On July 19, 2016, RIA Novosti reported the Russian Supreme Court had reduced the sentence (from 16 years to 15.5 years) of one of two radical Islamists convicted of plotting a terrorist attack in the mosque in the town of Pyt-Yakh in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug.

“The panel of judges has decided the verdict of the court, which sentenced Rizvan Agashirinov and Abdul Magomedaliyev to prison terms of 16 and 20 years, respectively, should be mitigated in the case of Agashirinov, and left in force in the case Magomedaliyev.”

On August 31, 2016, TASS reported the North Caucasus District Military Court had sentenced Russian national Rashid Yevloyev, a militant with the so-called Caucasus Emirate, to six years in a penal colony for planning terrorist attacks.

On February 15, 2017, Moskovsky Komsomolets reported the Moscow District Military Court had sentenced Aslan Baysultanov, Mokhmad Mezhidov, and Elman Ashayev. According to investigators, after returning in 2015 from Syria, where they had fought on the side of ISIL, Baysultanov and his accomplices had manufactured a homemade explosive device in order to carry out a terrorist attack on public transport in Moscow.

Baysultanov was sentenced to 14 years in prison; Ashayev, to 12 years, and Mezhidov, to 3 years.

On May 10, 2017, Interfax reported the North Caucasus District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don had sentenced ISIL recruiters who had been apprehended in Volgograd Region. The alleged ringleader, Raman Radzhabov, was sentenced to 4 years in prison after being found guilty of recruiting residents of Volgograd Region. His accomplices—Azamat Kurkumgaliyev, Gayrat Abdurasulov, Nurken Akhetov, and Idris Umarov—were found guilty of aiding and abetting Radzhabov, and given sentences of of 2 to 2.5 years in prison.

On May 30, 2017, RIA Novosti reported the ringleader of a failed terrorist attack in Kabardino-Balkaria, Adam Berezgov, had been sentenced to 7 years in prison. The defendant was found guilty of “planning a terrorist attack, illegally acquiring and carrying explosive substances or devices, and illegally manufacturing an explosive device.”

On July 27, 2017, TV Rain reported the Russian Supreme Court had increased by three years the sentence handed down to Ruslan Zeytullayev, who had been convicted and sentenced to 12 years for organizing in Crimea a cell of Hizb ut-Tahrir, an Islamist group banned in Russia. Zeytullayev’s sentence is now 15 years in prison.

On July 31, 2017, RIA Novosti reported the North Caucasus District Military Court had sentenced Ukrainian national Alexei Sizonovich to 12 years in a penal colony for involvement in planning a terrorist attack that was to have taken place in September 2016. The court ruled the 61-year-old defendant and an “unidentifed person” had, allegedly, established a group in Kyiv “for the commission of bombings and terrorist attacks in Ukraine and the Russian Federation.” It was reported the defendant “repented.”

On August 11, 2017, Lenta.Ru reported the North Caucasus District Military Court had sentenced 19-year-old Ukrainian national Artur Panov to 8 years in a medium-security penal colony for terrorism. Panov was found guilty of facilitating terrorism, planning a terrorist attack, and illegally manufacturing explosive substances. His accomplice, Maxim Smyshlayev, was sentenced to 10 years in a maximum-security penal colony.

At the trial, Panov pled guilty to calling for terrorism, and manufacturing and possessing explosives, but pled innocent to inducement to terrorism. Smyshlayev pled innocent to all charges.

On September 18, 2017, RIA Novosti reported a court in Rostov-on-Don had convicted defendants Tatyana Karpenko and Natalya Grishina, who were found guilty of planning a terrorist attack in a shopping mall. Karpenko was sentenced to 14.5 years in prison, while Grishina was sentenced to 9 years.

“The investigation and the court established Karpenko and Grishina were supporters of radical Islamist movements. […] From October 2015 to January 2016, the defendants planned to commit a terrorist attack in the guise of a religious suicide,” the Investigative Directorate of the SKR reported.

Fakes

On April 17, 2017, Memorial Human Rights Center issued a press release stating the case of the planned terrorist attack in the Moscow movie theater Kirghizia had been a frame-up. The human rights activists declared the 15 people convicted in the case political prisoners. It was a high-profile case. Novaya Gazeta wrote at the time that the MVD and FSB had insisted on pursuing terrorism charges, while the SKR had avoided charging the suspects with planning a terrorist attacking, accusing them only of possession of weapons in a multi-room apartment inhabited by several people who barely knew each other. It was then the case was taken away from the SKR.

Whatever the explanation for the trends we have identified, it is vital to note that Russian society is exceedingly poorly informed about the progress of the war on terrorism conducted by Russia’s special services, despite the huge number of reports about planned terrorist attacks. Due to the fact the names of the accused are hidden for some reason, and the court sentences that have been handed down are not made public in due form (even on specially designated official websites), it is impossible to evaluate the scale of the threat and the effectiveness of the special services, and to separate actual criminal cases from those that never went to court because the charges were trumped-up. Meanwhile, using media reports on prevented terrorist attacks for propaganda purposes contributes to an increase in aggressiveness and anxiety among the populace, who has no way of knowing whether all the apprehended terrorists have been punished, and whether this punishment was deserved.

Thanks to George Losev for the heads-up. Translated by the Russian Reader

Russian Orthodox Archpriest Vsevolod Chaplin, Russian MP Vitaly Milonov, and Alexander Malkevich presenting the National Values Defend Fund at a press conference at Rossiya Segodnya News Agency in Moscow in April 2019. Photo courtesy of Znak.com

Russian Orthodox Archpriest Vsevolod Chaplin, Russian MP Vitaly Milonov, and Alexander Malkevich presenting the National Values Defend Fund at a press conference at Rossiya Segodnya News Agency in Moscow in April 2019. Photo courtesy of Znak.com

“Tomorrow, the whole world will write about this. I am proud of my profession. #FreeIvanGolunov…” Vedomosti.ru: Vedomosti, Kommersant, and RBC will for the first time…” Screenshot of someone’s social media page by Ayder Muzhdabaev. Courtesy of Ayder Muzhdabaev

“Tomorrow, the whole world will write about this. I am proud of my profession. #FreeIvanGolunov…” Vedomosti.ru: Vedomosti, Kommersant, and RBC will for the first time…” Screenshot of someone’s social media page by Ayder Muzhdabaev. Courtesy of Ayder Muzhdabaev

Photo by the Russian Reader

Photo by the Russian Reader Russia does not have to worry about a crisis of democracy. There is no democracy in Russia nor is the country blessed with an overabundance of small-d democrats. The professional classes, the chattering classes, and much of the underclass, alas, have become accustomed to petitioning and beseeching the vicious criminal gang that currently runs Russia to right all the country’s wrongs and fix all its problems for them instead of jettisoning the criminal gang and governing their country themselves, which would be more practically effective. Photo by the Russian Reader

Russia does not have to worry about a crisis of democracy. There is no democracy in Russia nor is the country blessed with an overabundance of small-d democrats. The professional classes, the chattering classes, and much of the underclass, alas, have become accustomed to petitioning and beseeching the vicious criminal gang that currently runs Russia to right all the country’s wrongs and fix all its problems for them instead of jettisoning the criminal gang and governing their country themselves, which would be more practically effective. Photo by the Russian Reader

Focus group drawing from the study “Autumn Change in the Minds of Russians: A Fleeting Surge or New Trends?” The first panels is labeled “Now.” The second panel shows a drunken Russia at the bottom of the stairs “in five years,” while “the US, Europe, Canada, China, [and] Japan” stand over it dressed in swanky business suits. The third panel is entitled “Friendship.” Source:

Focus group drawing from the study “Autumn Change in the Minds of Russians: A Fleeting Surge or New Trends?” The first panels is labeled “Now.” The second panel shows a drunken Russia at the bottom of the stairs “in five years,” while “the US, Europe, Canada, China, [and] Japan” stand over it dressed in swanky business suits. The third panel is entitled “Friendship.” Source:  Judicial district construction site in Petersburg. Photo courtesy of Stanislav Zaburdayev/TASS and RBC

Judicial district construction site in Petersburg. Photo courtesy of Stanislav Zaburdayev/TASS and RBC The future judicial quarter in Petersburg is currently a giant sandbox. Photo courtesy of Alexander Koryakov/

The future judicial quarter in Petersburg is currently a giant sandbox. Photo courtesy of Alexander Koryakov/ Yevgeny Prigozhin. Photo courtesy of Mikhail Metzel/TASS and RBC

Yevgeny Prigozhin. Photo courtesy of Mikhail Metzel/TASS and RBC A fruits and vegetables stall at the famous Hay Market (Sennoy rynok) in downtown Petersburg, September 29, 2018. Photo by the Russian Reader

A fruits and vegetables stall at the famous Hay Market (Sennoy rynok) in downtown Petersburg, September 29, 2018. Photo by the Russian Reader “Caloric Value of the Russian Diet.” The blue line indicates caloric value, while the dotted line indicates the recommended daily caloric intake per family member in kilocalories. The light purple area indicates the number of Russians who suffer from obesity, in thousands of persons, while the shaded dark purple area indicates the number of Russia who suffer from anemia, also in thousands of peoples. Source: Rosstat and RANEPA. Courtesy of Republic

“Caloric Value of the Russian Diet.” The blue line indicates caloric value, while the dotted line indicates the recommended daily caloric intake per family member in kilocalories. The light purple area indicates the number of Russians who suffer from obesity, in thousands of persons, while the shaded dark purple area indicates the number of Russia who suffer from anemia, also in thousands of peoples. Source: Rosstat and RANEPA. Courtesy of Republic Jonathan Pryce and Terry McKeown in Brazil (1985). Courtesy of

Jonathan Pryce and Terry McKeown in Brazil (1985). Courtesy of  In Kandor City, on the planet Krypton, everyone fears the mysterious, awe-inspiring Voice of Rao, including the little “rankless” priestess Ona. Still from the TV serial

In Kandor City, on the planet Krypton, everyone fears the mysterious, awe-inspiring Voice of Rao, including the little “rankless” priestess Ona. Still from the TV serial  Inmates working in a prison sewing factory. Mordovia, Russia, March 20, 2007. Photo: Yuri Tutov/PhotoXPress. Courtesy of

Inmates working in a prison sewing factory. Mordovia, Russia, March 20, 2007. Photo: Yuri Tutov/PhotoXPress. Courtesy of