Let’s think about who the beneficiaries are and what their profit is: this should explain why the regime is stable. The beneficiaries include not only the supreme leader, who of course wants to be “mistress of the seas” and has been trying consolidate the regime for himself and his entourage. The beneficiaries also include different groups among the elites, the security forces, officialdom, businessmen, and “intellectuals” at all levels. Material and symbolic resources are now funneled to these groups, and they are granted new powers to cause mayhem in their own bailiwicks. Many of them have taken advantage of this opportunity to quash rivals and take up new positions in their respective economic, political, and cultural markets. The beneficiaries also include different sectors of the populace—for example, people employed in the defense industry, people employed by law enforcement agencies, people who volunteer for the army as contract soldiers, and people engaged in producing different kinds of propaganda. They amount to millions of people, and the streams of financing that nourish them flow far and wide. In addition to power and material gain, there is a psychological benefit: one can now openly be proud of one’s country and hate its “enemies.” How many of the insulted and injured now feel joy and have made their own complexes the norm. This satisfaction also costs money, and it means millions more in new profits.

Source: Sergey Abashin (Facebook), 2 August 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader

“These amendments are written for a big war and general mobilisation. And the smell of this big war can already be scented,” Andrei Kartapolov, the head of the Duma’s defence committee, said this week as the Russian parliament rushed to adopt a new law. The legislation enabling the Kremlin to send hundreds of thousands more men into combat reveals a sad truth: that far from seeking an off-ramp from his disastrous war in Ukraine, Vladimir Putin is preparing for an even bigger war.

It is understandable that many in Ukraine and the west want to believe that Russia’s president is cornered. The Ukrainian army is gradually reconquering lands occupied by the Russians and has shown itself capable of striking deep into enemy territory — even into the Kremlin itself. The sanctions pressure on Russia is mounting.

For now, the west remains united in support of Kyiv, and streams of modern weaponry and money sustain the Ukrainian war effort. Finally, the mutiny staged by the Wagner mercenary boss Yevgeny Prigozhin and visible conflicts among senior Russian military commanders add to hopes that the Kremlin’s war machine will break down.

Things likely look very different to the Kremlin, which believes that it can afford a long war. The Russian economy is forecast to record modest growth this year, mostly thanks to military factories working around the clock. Critical components such as microchips needed for the defence industry are arriving from China and other sources.

Despite sanctions, the Kremlin’s war chest is still overflowing with cash, thanks to windfall energy profits last year and also to the adaptability of Russian commodities exporters, who have found new customers and who settle payments mostly in yuan. If budgetary pressures were to become more acute, Russia’s central bank could further devalue the rouble, making it easier to pay soldiers, defence industry workers and the internal security forces who keep the Russian elite and public repressed and largely in line with Putin’s disastrous course.

When it comes to the war itself, the Kremlin still seems unperturbed by the Ukrainian counteroffensive. Even if Kyiv makes more advances, the Kremlin may brush them off as temporary. Putin is banking on the fact that the Russian manpower that can potentially be mobilised is three to four times bigger than Ukraine’s, and the only pressing task is to be able to tap into that resource at will: to mobilise many more men, arm them, train them and send them to fight. This is precisely the purpose of the new law, which should help the Kremlin to avoid another official mobilisation.

From now on, the government can quietly send draft notices to as many men as it deems necessary. The upper age limit for performing mandatory service will be increased from 27 to 30, and could be raised again in future. Once an electronic draft notice is issued, Russia’s borders will be immediately closed to its recipient in order to prevent a massive exodus of military-age men like the one Russia witnessed last autumn. The punishments for refusing to serve have also been ramped up. These moves, combined with massive state investment in expanding arms production, should help Putin to build a bigger and better equipped army.

A parallel tactic is the strangulation of Ukraine’s economy. Knowing that the Ukrainian budget is on life support provided by its western allies, the Kremlin wants to deny Kyiv all sources of revenue. Moscow has therefore not only pulled out of the grain deal that had enabled Ukrainian agricultural exports via the Black Sea, it has also launched massive air strikes against Ukrainian ports to destroy any possibility of reviving the agreement. The same logic underpins Russia’s air strikes against civilian infrastructure: they are aimed at making Ukrainian cities uninhabitable and preventing reconstruction efforts.

The Kremlin hopes that the rapid rebuilding of the Russian army and gradual decimation of the Ukrainian economy and armed forces will result in growing western frustration and a decline in material support for Kyiv. To speed up this process and break the west’s will, Moscow is using threats of escalation, including expansion of the conflict towards Nato territory via Belarus with the help of Wagner mercenaries based there.

Putin has made plenty of fatal mistakes. But as long as he is in charge, Moscow will dedicate its still vast resources to achieving his obsession with destroying and subordinating Ukraine. As western leaders think about policies to support Ukraine into the third year of this ugly war, any long-term strategy must take this reality into account.

Source: Alexander Gabuev, “Putin is looking for a bigger war, not an off-ramp, in Ukraine,” Financial Times, 30 July 2023. Thanks to Monique Camarra (EuroFile) for the heads-up.

Things like this also get written: “Is it just Putin’s war or a war on the part of all Russians? Perhaps neither one nor the other. Another sociological hypothesis is that the cynical elite has provided the real support for the military aggression, rather than a grassroots gone bad.” (This is a headline: you can google it.). Further, the authors define “the cynical elite” as “the mid-level and low-level officials who ensure the functioning of the Kremlin’s military-political machine; the para-state businesses engaged in import substitution and circumventing sanctions; the upper middle class and the leadership of so-called public sector entities, compelled in one way or another to demonstrate loyalty to the war”—that is, only a few million people. In other words, the Russian ruling class supports the foreign policy that the Russian state pursues in the interests of the Russian ruling class. This argument is tautological in the Marxist manner (although, as the authors of the article rightly point out, it occurs to very few people) and is not entirely true, because there are groups within the ruling class who do not benefit at all from this policy. But it certainly sounds more convincing than the theory of a “grassroots gone bad.”

Source: Grigorii Golosov (Facebook), 2 August 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader

I reread our interview with Dima Spirin [leader of the recently dissolved veteran Russian punk rock band Tarakany!], and one phrase cut me to the quick: “Our attempt to be free in an unfree country has failed.” An ordinary argument, seemingly, and it’s been made a hundred times. There were oases of freedom in Russia, but then they were destroyed and everything collapsed.

Such things are usually spoken of with regret, as of disappointed hopes. But oases of freedom in a poor dying country are not terribly moral, by and large. Do you know who was free in ancient Greece? That’s right, slaveholders. All the others were slaves.

Does this mean it isn’t worth fighting for freedom in an unfree country? It doesn’t mean that at all. But what’s worth fighting for is everyone’s freedom, not just one’s own. There is no separate freedom for fifteen percent of the population. That is called colonialism.

Some have it good, while others have it bad. Some are free, while others are slaves. Some are rich, while others are poor. There is no other way. Or rather, there is another way, but it ends exactly as it has now—in enormous bloodshed.

It’s either everyone or no one: freedom is not achieved piecemeal.

This is our collective fault. Our guilt is terrible and bloody. I don’t excuse myself either.

And the inner freedom that is the talk of the town nowadays is a lame excuse, like inner emigration. The madman and the drunkard are truly free. But neither meditation, nor reading Borges, nor listening to psychedelic rock will save you from hunger, cold, or getting smacked with a billy club. And they won’t cancel the fact that your neighbor has it bad.

A woman falls on the street, breaks her leg, and lies on the ground screaming. But you’re listening to Pink Floyd on your headphones: you’re free.

Source: Yan Shenkman (Facebook), 3 August 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader

Azat Miftakhov. Photo: Victoria Odissonova/Novaya Gazeta

Azat Miftakhov. Photo: Victoria Odissonova/Novaya Gazeta Penza Network defendants during the reading of the verdict. Photo: Victoria Odissonova/Novaya Gazeta

Penza Network defendants during the reading of the verdict. Photo: Victoria Odissonova/Novaya Gazeta

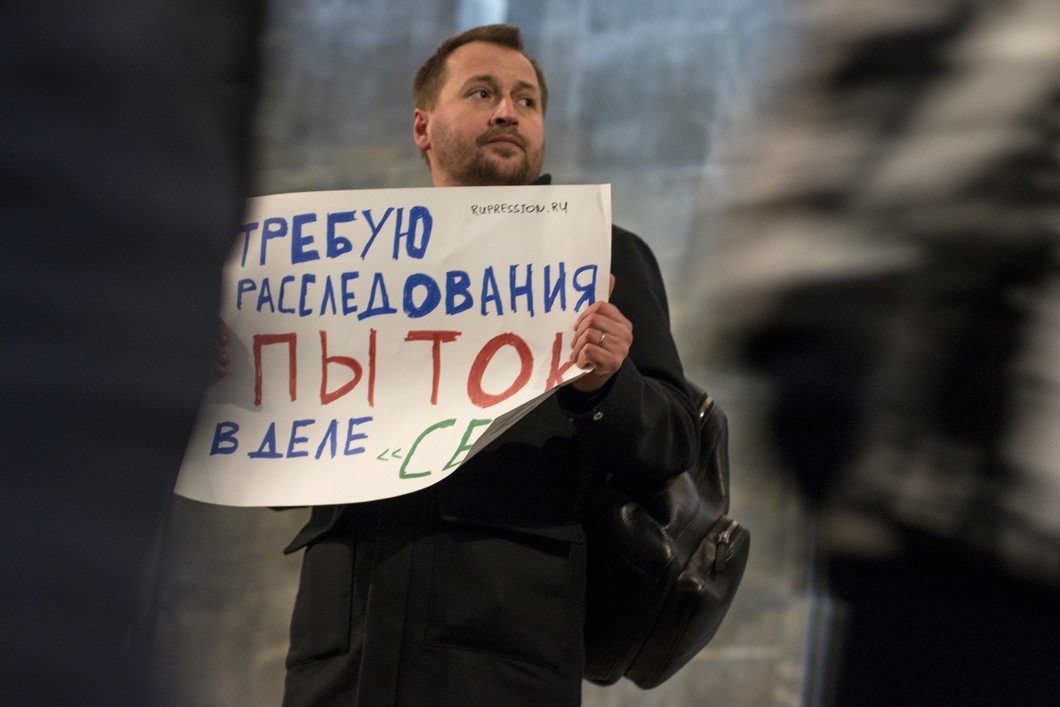

Viktor Filinkov and Yuli Boyarshinov. Photo: David Frenkel/Mediazona

Viktor Filinkov and Yuli Boyarshinov. Photo: David Frenkel/Mediazona Photo courtesy of Sota.Vision and Novaya Gazeta

Photo courtesy of Sota.Vision and Novaya Gazeta Dmitry Pchelintsev. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

Dmitry Pchelintsev. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta The Penza Network Case defendants during the trial. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

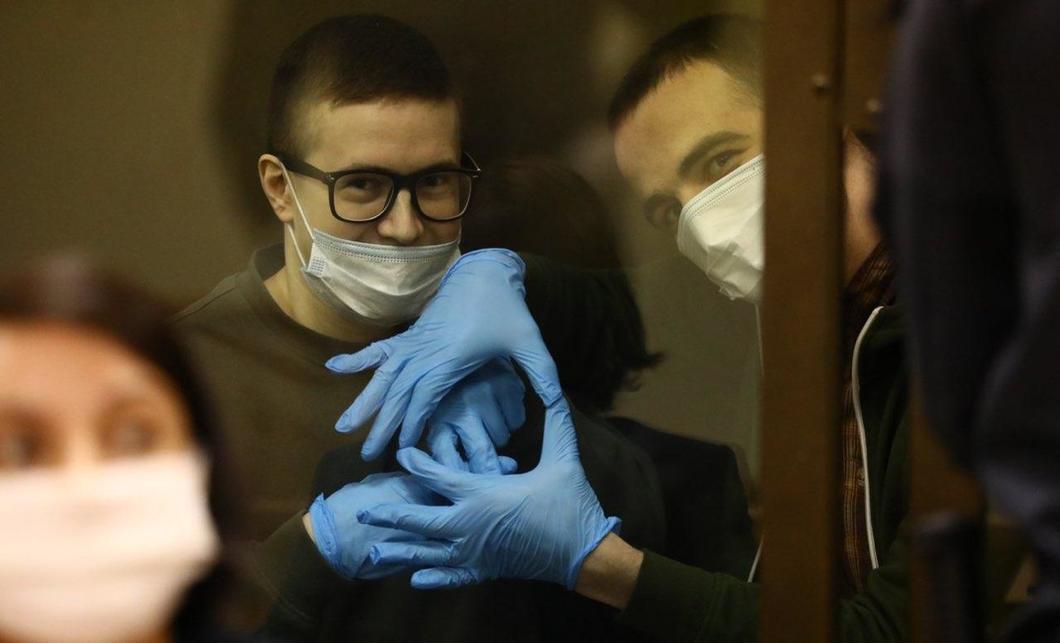

The Penza Network Case defendants during the trial. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta The defendants communicate with their relatives. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

The defendants communicate with their relatives. Photo by Alexei Obukhov. Courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

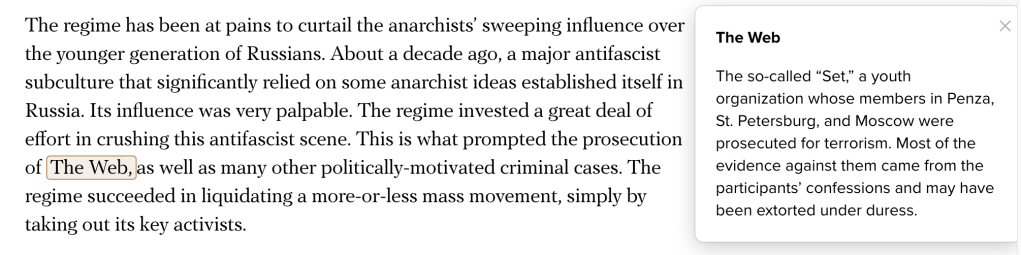

Police detained over forty activists during the protest on Lubyanka Square. Photo by Valery Sharifulin. Courtesy of TASS and BBC Russian Service

Police detained over forty activists during the protest on Lubyanka Square. Photo by Valery Sharifulin. Courtesy of TASS and BBC Russian Service According to Lev Ponomaryov, police roughed up protesters when detaining them. Photo by Valery Sharifulin. Courtesy of TASS and BBC Russian Service

According to Lev Ponomaryov, police roughed up protesters when detaining them. Photo by Valery Sharifulin. Courtesy of TASS and BBC Russian Service A photo of Lev Ponomaryov after his “rough handling” by police in Moscow on March 14, 2020. The photo was widely disseminated on Russian social media. Courtesy of

A photo of Lev Ponomaryov after his “rough handling” by police in Moscow on March 14, 2020. The photo was widely disseminated on Russian social media. Courtesy of