Network: Parents of Anarchists versus the FSB

Alexei Polikhovich and Ksenia Sonnaya

OVD Info

July 30, 2018

Members of the Parents Network. Photo courtesy of OVD Info

Members of the Parents Network. Photo courtesy of OVD Info

Eleven antifascists from Penza and Petersburg have been charged in the case against the alleged “terrorist community” known as the Network. Many people have got used to news of the violence, threats, and electrical shock torture used against the suspects in the case, but the accused themselves and their loved ones will probably never grow inured to such things. The parents of the accused came together in a committee known as the Parents Network. They have been trying to do something to help their loved ons.

The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) claims the Network is an international organization. Aside from Penza and Petersburg, secret cells were, allegedly, established in Moscow and Belarus. Yet no one has been arrested either in Russia’s capital or abroad. Meanwhile, the Parents Network is definitely an international organization. Aside from Penza, Petersburg, Moscow, and Novosibirsk, the committee has members in Petropavlovsk, the city in Kazakhstan where Viktor Filinkov’s mother lives.

Members of the Parents Network have appeared at two press conferences, in April and May of this year. They have established a chatroom on Telegram where they discuss new developments in the case, exchange opinions, share impressions of hearings and interrogations, and give each other support. In addition, the parents try and force reactions from Russian government oversight and human rights bodies. They write letters to Russia’s human rights ombudsman and the Presidential Human Rights Council, and file complaints with the Investigative Committee and the Russian Bar Association.

OVD Info spoke with members of the Parents Network.

Tatyana Chernova, Andrei Chernov’s mother, shop clerk

All this kicked off in March at the next-to-last custody extension hearing in Penza.

I went to see Ilya Shakursky. I knew reporters and human rights advocates would be there. I just approached the people who had come to the hearing and asked for help. One of those people was Lev Ponomaryov, leader of the movement For Human Rights. He responded and proposed meeting in Moscow.

I didn’t know any human rights activists. I didn’t know where to go or to whom to turn, since I’d never dealt with this. When I’d discuss it with my daughter, she would scold me, telling me we had to wait or we might make things worse.

My husband and I went to see Lev Ponomaryov. We said we didn’t know what to do. We had a lawyer. Our lawyer did his job, while we, the parents, didn’t know how to help. We were told to take a pen and sign up, that the first thing to do was unite with all the other parents. I found their telephones numbers and gradually called all of them.

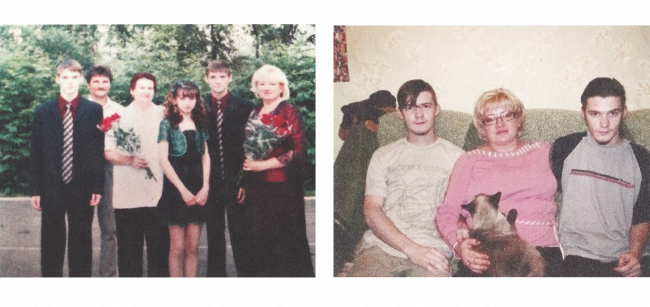

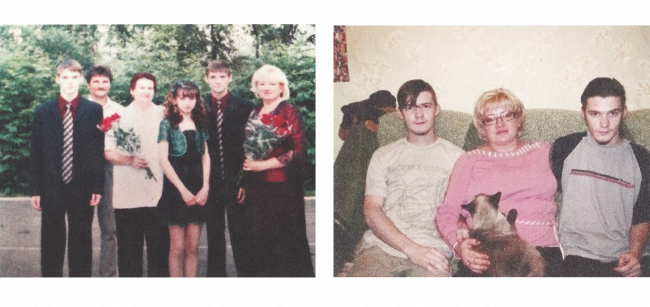

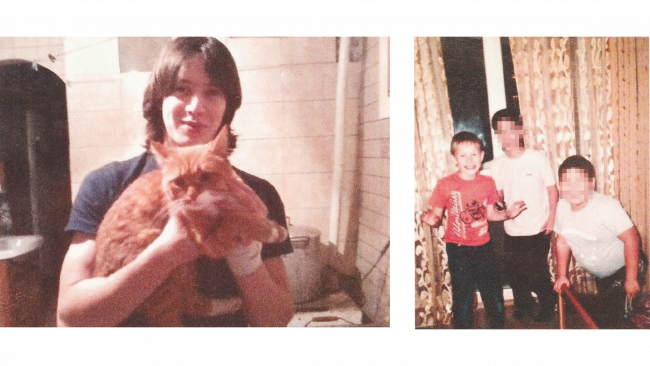

Andrei Chernov’s family

Andrei Chernov’s family

I couldn’t get hold of Lena Shakurskaya. I sent her an SMS, saying I’m so-and-so’s mom, I want to talk, if you want to talk, write. She called me right back. Everyone was probably waiting for it. We shared a misfortune, and it brought us together. Our first meeting was at Lev Ponomaryov’s office. Lena came to Moscow for the meeting. It was only there she heard the whole truth. Mikhail Grigoryan, Ilya’s former lawyer, had been telling her a different story. The Pchelintsevs met her. They told her what was going on. Lena was made sick by what she found out.

We try to have each other’s backs. The blows are such that it’s hard to take. Yes, I have friends. But I can call Sveta Pchelintseva or Lena Bogatova, say, knowing they’ll know where I’m coming from, because this is part of our personal lives.

Yelena Bogatova, Ilya Shakursky’s mother, shop clerk

We had a lawyer, Mikhail Grigoryan. He warned me against communicating with the relatives of the other lads. He said each of us had to defend their own son. Nothing good would come of fraternizing. I listened to him.

In March, I saw Andrei Chernov’s mom. Again, at Grigoryan’s insistence, I didn’t go up to her or chat with her. Later, I had doubts. I wanted to talk to someone. God was probably reading our minds: it was then Tatyana Chernova sent me an SMS. We got in touch on the phone. I went to Moscow without telling the lawyer. We met with human rights activists. We discussed how to talk about the kids.

It’s really rough when you’re on your own in these circumstances, but now we are together. You realized you’re not alone and our boys are not alone. What we do is mainly for them. We put on these t-shirts when we go to hearings so they can see we are fighting. We have gone to all the hearings together so they see we’re all together.

At first, I was a “cooperative” mom. I was friendly with the investigator. We would talk. He said unflattering things about the other parents. Grigoryan would ask me to meet with Ilya to “talk sense” into him. The investigator would talk to me, telling me that if I was a good mom, I would get the message through his head, that is, if we had a good relationship, as I had told him. Then I would get to see Ilya for ten minutes.

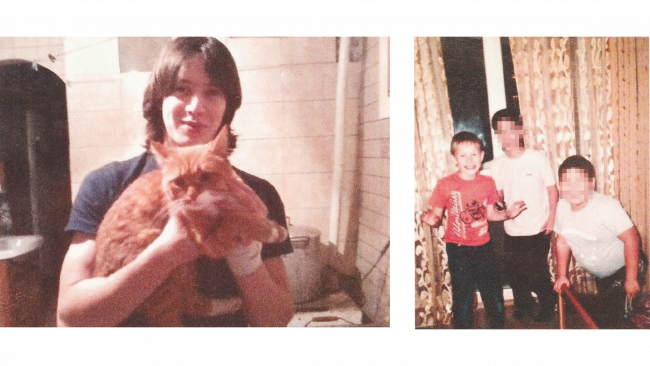

Yelena Bogatova and Ilya Shakursky

Yelena Bogatova and Ilya Shakursky

In February, when Ilya signed a statement saying he had not been tortured, his uncle and I persuaded him to sign the paper. We didn’t understand a thing, of course. Grigoryan said Ilya had to sign the paper. He said he was working for us and Ilya shouldn’t be obstinate, but should sign everything he asked him to sign.

Ilya stared at me.

“Mom, what are you doing?” he said. “I’m not guilty of anything.”

“Sign it or things will get worse for you, and I’ll have it worse. I won’t see you again,” I said to him.

I was selfish, drowning in my own grief. I pushed my son into doing it because I felt sorry for myself. The FSB used me. Yes, you can see him, but make him to sign this. Hold his hand.

It’s psychologically easier for me now. I feel strong inside. I have the confidence to keep going and try and rescue the boys from the paws of the FSB. I don’t have any friends per se anymore. At first, they would call and ask about things, but then they would do it less and less often. I don’t know, maybe they’re afraid of the FSB. They’re afraid of calling me once too much because they know my phone is bugged.

On the other hand, I have a sense of how many friends Ilya has. I communicate with the Parents Committee and Ilya’s friends, who are not afraid of anything. We talk on the phone. They visit Ilya’s grandma and help. They water the garden and go to the store, just like Timur and his friends.

Natalya, Viktor Filinkov’s mom, businesswoman

It was like a bolt out of the blue. Viktor’s wife, Alexandra, wrote to me. I was ready to go see him that very minute, but I was told it would be better for me not to show up in Russia for the time being. I live in Petropavlovsk in northern Kazakhstan, which is not far from Omsk. It’s sixty kilometers to the Russian border.

Then I could not wait any longer. I said I was going to Petersburg, come what may. Everyone was surprised I was allowed to see him. I was the first parent allowed to see their child. But it was so little time. It was so hard to talk to him through the glass.

“Mom, I’ve been tortured,” he said.

I could see he had a scar. He told me to stay strong and be reasonable about what was happening.

Viktor Filinkov

Viktor Filinkov

I’d never been interested in politics. Now, though, I’m interested. I’m interested in Russian politics and Kazakhstani politics, and I read all the news straight through. I read about what incidents happened where, who was tortured where, who has been framed, who has been protected. I read everything about what’s happened to antifascists and anarchists everywhere.

I think about why I don’t live in Russia, in Petersburg. I cannot move right now. It’s complicated to do the paperwork, register as an immigrant, and get a temporary resident permit. The thing that causes me the most pain is the thought they could ban me from entering the country.

Nikolai Boyarshinov, Yuli Boyarshinov’s father, artist

It’s a terrible state, which everyone has been through, when you suddenly find out your son has been arrested, and the charges are so absurd. You have no idea at all what to do. It’s a wall against which you beat your head. You quite quickly realize you’re completely powerless.

I joined the Parents Network when it had quite a few members. I was completely crushed then. At first, I imagined it existed for its own sake, to keep from going insane. But then I noticed it got results. By then I had completely recovered from my initial state, so I did things, thought about things, and discussed things. Being involved in the Parents Network was my salvation.

We have a chat page on Telegram. In contrast to the Network, which the FSB concocted, we don’t hide the fact we have a Network. If you think our children organized a criminal Network, then our Network is probably criminal, too.

Our actions get few results, perhaps, but it is this way, bit by bit, that you build up the desire to do something to improve the conditions in which the boys are incarcerated. Publicity was their salvation, after all. It’s not a matter of getting them released yet. We are still thinking about how to keep them alive.

That was how it happened with my son. I saw him at the first custody extension hearing, a month after his arrest. I saw what he looked liked when he arrived at the courthouse. He looked drab and battered. He had fresh bruises on his head. You could see that it couldn’t go on for long like that. His friends, thirty people or so, came to the next hearing. When he saw everyone, he was happy. A new phase began after that. It was clear that at least they wouldn’t kill him.

Yuli Boyarshinov in childhood

It was a turning point for me. When everything went public, it saved my son’s life. Yet now I’m afraid the publicity will die down and the boys will again be isolated, and the nightmare will recommence. That’s why I never turn down an interview.

I go out picketing on Fridays. I had doubts when the World Cup was underway. The first day I had the sense I was preventing people from enjoying themselves, but I decided to keep going out. Something unexpected happens each time. A young man came up to me and said he knew nothing about the Network. He walked away, apparently looked in the internet, and came back. I told him about the other boys.

“I don’t share those views,” he said.

“It doesn’t matter now whether you’re leftist or rightist,” I replied. “What matters is that you have views, and that is sufficient grounds to arrest you and charge you with a crime.”

The Parents Network is now like a family. We’ve agreed that when this travesty of justice is over, we will definitely have a reunion with everyone. Everyone has become family. Viktor’s mom lives in Kazakhstan, and his wife had to escape, so when I take care packages to Yuli, I take packages for Viktor, too. I really want to meet all the boys. I’m worried sick about all of them. My wife sometimes reads an article about Dima Pchelintsev or Viktor, and she cries. We feel like they’re our children.

Yelena Strigina, Arman Sagynbayev’s mother, chief accountant

The first to get together were the people in Penza, the Pchelintsevs and the Chernovs. I joined along the way. The defense lawyers had to sign a nondisclosure agreement, so we had to go public with all our problems.

I live in Novosibirsk. We all stay in touch through a certain banned messenging site. When we were at the hearings in Penza, we made t-shirts emblazoned with the logo “Free [son’s surname].” It might look like a game to outsiders, but we have to stay afloat. It’s important to do something. And to publicize everything that happens.

Arman Sagynbayev and his niece. Screenshot from the website of the Best of Russia competition (left); photo of a billboard in Moscow (right)

Arman has a serious chronic illness. There was no point in torturing him. His first testimony was enough to send him down for ten years. He testified against himself more than he did against the others. He was extradited from Petersburg to Penza. Along the way, the men who were transporting him opened the doors when they were in the woods and dragged Arman out. They promised to bury him alive. That was at night. In the morning, he was taken to the investigator for questioning. When people are under that kind of pressure, they would say anything. I would say I’d attempted to invade Kazan and blow up chapels.

Arman Sagynbayev in childhood

I kept the story secret from friends and relatives. But after the film about the case on NTV, everyone called and started looking funny at me. The news even made it to the school that Arman’s little brother attends. Imagine: your brother is a terrorist. It was a good thing honest articles had been published at that point. I would send people links to them. Thanks to those articles, people read a different take on events, and we have been protected from a negative reaction from society.

Svetlana Pchelintsev, Dmitry Pchelintsev’s mother, cardiologist

The Parents Network has empowered us a hundredfold. By joining together, we are no longer each fighting for our own son, we are fighting for all the boys. We love kids we don’t know at all, kids who are complete strangers, as if they were our own kids. Our hearts ache for each of them. I think it’s wonderful. A whole team of parents fighting for all the boys. What can stop parents? Nothing can stop them.

What has happened is terrible. Whether we like or not, we have to go on living while also helping the children. So, when one mom has a moment of weakness, she can telephone another mom, who is feeling the opposite emotions. It’s vital when a person hears that support.

Dmitry Pchelintsev in childhood

Dmitry Pchelintsev, Dmitry Pchelintsev’s father, engineer

We are a committee of parents. What we do is support each other. We live in Moscow, but our son is jailed in Penza. The parents who live in Penza visit our son. Our kids, as it turns out, belong to all of us. We were in Penza and we gave all the children all their care packages at the same time. If we talk with the warden of the remand prison, we speak on behalf of all the kids.

This has helped us and helped our children. We get emotional support. It’s one thing when you sit alone in a closed room and don’t know what’s happening to your child. It’s another thing when all the parents meet and discuss everything. Tiny facts come together into a big picture, and you more or less understand what’s happening.

In my view, publicity is quite effective. This has been borne out by the actions of the case investigator, Tokarev. If it makes Tokarev uncomfortable, if it makes Tokarev angry, it’s a good thing. As he said, “You raised this ruckus in vain. They would have been in prison long ago.” So, what’s bad for him is good for me. I visited the offices of the Investigative Committee in Penza. They couldn’t believe it was possible the FSB would torture people in a remand prison.

Lena, Ilya Shakursky’s mom, said Tokarev always referred to us and the Chernovs as “uncooperative” parents. He complained that, if it weren’t for us, our kids would have been sentenced to two years each in prison and that would have been it. How can a person say such things? You put a man in jail for nothing, and then you sit and clap.

The FSB are Putin’s hellhounds. Putin loosened their leash a little, and they grabbed everyone they could before the presidential election and the World Cup. Now it’s all coming to an end, and he’ll again say, “Heel!” Let’s see where it leads. Perhaps the plug will be pulled, unfortunately.

All photos courtesy of the parents and relatives of the accused and OVD Info. Translated by the Russian Reader.

***************

What can you do to support the Penza and Petersburg antifascists and anarchists tortured and imprisoned by the FSB?

- Donate money to the Anarchist Black Cross via PayPal (abc-msk@riseup.net). Make sure to specify your donation is earmarked for “Rupression.”

- Spread the word about the Network Case aka the Penza-Petersburg “terrorism” case. You can find more information about the case and in-depth articles translated into English on this website (see below), rupression.com, and openDemocracyRussia.

- Organize solidarity events where you live to raise money and publicize the plight of the tortured Penza and Petersburg antifascists. Go to the website It’s Going Down to find printable posters and flyers you can download. You can also read more about the case there.

- If you have the time and means to design, produce, and sell solidarity merchandise, please write to rupression@protonmail.com.

- Write letters and postcards to the prisoners. Letters and postcards must be written in Russian or translated into Russian. You can find the addresses of the prisoners here.

- Design a solidarity postcard that can be printed and used by others to send messages of support to the prisoners. Send your ideas to rupression@protonmail.com.

- Write letters of support to the prisoners’ loved ones via rupression@protonmail.com.

- Translate the articles and information at rupression.com and this website into languages other than Russian and English, and publish your translations on social media and your own websites and blogs.

- If you know someone famous, ask them to record a solidarity video, write an op-ed piece for a mainstream newspaper or write letters to the prisoners.

- If you know someone who is a print, internet, TV or radio journalist, encourage them to write an article or broadcast a report about the case. Write to rupression@protonmail.com or the email listed on this website, and we will be happy to arrange interviews and provide additional information.

- It is extremely important this case break into the mainstream media both in Russia and abroad. Despite their apparent brashness, the FSB and their ilk do not like publicity. The more publicity the case receives, the safer our comrades will be in remand prison from violence at the hands of prison stooges and torture at the hands of the FSB, and the more likely the Russian authorities will be to drop the case altogether or release the defendants for time served if the case ever does go to trial.

- Why? Because the case is a complete frame-up, based on testimony obtained under torture and mental duress. When the complaints filed by the accused reach the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg and are examined by actual judges, the Russian government will again be forced to pay heavy fines for its cruel mockery of justice.

***************

If you have not been following the Penza-Petersburg “terrorism” case and other recent cases involving frame-ups, torture, and violent intimidation by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and other arms of the Russian police state, read and republish the recent articles the Russian Reader has posted on these subjects.

- “Network: Parents versus the FSB,” 2 August 2018

- “Is Maxim Shulgin an ‘Extremist’?” 26 July 2018

- “Moscow City Court Affirms Anna Pavlikova’s Remand in Custody,” 26 July 2018

- “Is Lydia Bainova an ‘Extremist’?” 24 July 2018

- “Anna Pavlikova: Enemy of the Putinist State?” 22 July 2018

- “A Funny Thing Happened in Pryamukhino,” 20 July 2018

- “Two More Suspects Detained in Network Case,” 6 July 2018

- “Petersburg Court Bailiffs Attack Reporter at Network Case Hearing,” 20 June 2018

- “Anna Tereshkina: At the Court Hearing,” 20 June 2018

- “Nikolai Boyarshinov: I Hope One Day We Can Say the FSB Has Been Banned,” 12 June 2018

- “Lemmy Kilmister vs. Vladimir Putin,” 19 May 2018

- “Brazil,” 18 May 2018

- “This Is What Antifascism Looks Like,” 13 May 2018

- “May Day in Petersburg: ‘Your Torture Won’t Kill Our Ideas,’” 2 May 2018

- “Riot Cops Raid Punk Rock in Barnaul: ‘Freaks, Not Patriots,” 29 April 2018

- “Hug Your Son and We’ll Open Fire,” 27 April 2018

- “Denis Lebedev’s Suicide Note,” 26 April 2018

- “‘Are You a Bitch Yet?’ FSB Makes New Threats to Framed and Tortured Antifascist Viktor Filinkov,” 26 April 2018

- “Suicide Invoice,” 25 April 2018

- “Zoya Svetova: Interview with Petersburg Public Monitoring Commission Members Yana Teplitskaya and Yekaterina Kosarevskaya,” 23 April 2018

- “TV Party Tonight!” 21 April 2018

- “Valery Pshenichny: Tortured, Then Murdered,” 19 April 2018

- “They Are Not Terrorists! The Terrorists at the FSB Torture People,” 16 April 2018

- “FSB and NTV Pressure Mother of Man Accused in ‘Terrorist’ Frame-Up,” 12 April 2018

- “A New Face in Hell: Yuli Boyarshinov,” 12 April 2018

- “Wife of Tortured Antifascist Seeks Asylum in Finland,” 11 April 2018

- “The FSB’s Tall Tales,” 10 April 2018

- “Families of Penza-Petersburg Terrorists Form Committee,” 9 April 2018

- “Extremism Inside Out,” 30 March 2018

- “Search and Intimidate,” 29 March 2018

- “Solidarity? (The Case of the Penza and Petersburg Antifascists),” 24 March 2018

- “Anna Tereshkina: At Viktor Filinkov’s Remand Extension Hearing,” 23 March 2018

- “Ping, Ping, Ping: The Remand Extension Hearing of the Penza ‘Terrorists,’” 20 March 2018

- “Tortured Petersburg Antifascist Viktor Filinkov Transferred to Remand Prison in Leningrad Region,” 17 March 2018

- “Svyatoslav Rechkalov: ‘They Proceeded to Pull Down My Trousers, Threatening to Shock Me in the Groin,’” 15 March 2018

- “They Jump on Anything That Moves, Part 3: The Case of the New Greatness Movement,” 15 March 2018

- “The Horrorshow Continues: Svyatoslav Rechkalov Tortured in Moscow,” 15 March 2018

- “The Rowdies Have to Be Apprehended Legally, So We Can Have a Celebration in the City on March 18, not Bedlam,” 15 March 2018

- “Ilya Kapustin: ‘When the Stamp Thudded in My Passport, It Was Like a Huge Weight Had Been Lifted from My Shoulders,’” 13 March 2018

- “Your Husband Safely Made the Flight to Minsk after We Abducted Him in Petersburg,” 2 March 2018

- “‘FSB Officers Always Get Their Way!’” 28 February 2018

- ‘The Case of the Anarchists: Disappearances, Torture, Frame-Up (11 AM, February 15, 2018, Moscow),” 14 February 2018

- “The Strange Investigation of a Strange Subway Attack,” 12 February 2018

- “Arrested Penza Antifascists Talk about Torture in Remand Prison,” 10 February 2018

- “Solidarity with Persecuted Russian Antifascists and Anarchists in NYC and Minneapolis,” 7 February 2018

- “Ilya Kapustin: ‘They Said They Could Break My Legs and Dump Me in the Woods,’” 31 January 2018

- “The Penza ‘Terrorism’ Case,” 30 January 2018

- “Breaking Bad with the FSB,” 29 January 2018

- “How ‘Stability’ Has Really Been Achieved in Russia,” 29 January 2018

Yevgeny Kurakin. Courtesy of Facebook and

Yevgeny Kurakin. Courtesy of Facebook and  Members of the Parents Network. Photo courtesy of OVD Info

Members of the Parents Network. Photo courtesy of OVD Info Andrei Chernov’s family

Andrei Chernov’s family Yelena Bogatova and Ilya Shakursky

Yelena Bogatova and Ilya Shakursky Viktor Filinkov

Viktor Filinkov

Patriotic Russian diabetics treat their disease only with domestically produced insulin, such as Rosinsulin, pictured here. Photo courtesy of

Patriotic Russian diabetics treat their disease only with domestically produced insulin, such as Rosinsulin, pictured here. Photo courtesy of  Putinist youth activist Nikita Smirnov. Photo courtesy of Novaya Gazeta

Putinist youth activist Nikita Smirnov. Photo courtesy of Novaya Gazeta In Finland

In Finland Screen shot of the message posted about Viktor Filinkov’s arrest on the Telegram channel of the Joint Press Service of the St. Petersburg Courts, January 25, 2018

Screen shot of the message posted about Viktor Filinkov’s arrest on the Telegram channel of the Joint Press Service of the St. Petersburg Courts, January 25, 2018 If you’re a sucker for rigged elections and skewed opinion polls, like most western journalists, you would have to admit that Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov is Russia’s most popular politician, not Vladimir Putin. Photo courtesy of RFE/RL

If you’re a sucker for rigged elections and skewed opinion polls, like most western journalists, you would have to admit that Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov is Russia’s most popular politician, not Vladimir Putin. Photo courtesy of RFE/RL Poster: “March 18, 2018. Russian Presidential Election. Russian Central Election Commission.” || Graffiti: “This is not an election.” Dixie grocery store, Central District, Petersburg. Photo by the Russian Reader

Poster: “March 18, 2018. Russian Presidential Election. Russian Central Election Commission.” || Graffiti: “This is not an election.” Dixie grocery store, Central District, Petersburg. Photo by the Russian Reader

Rally by Alexei Navalny’s supporters in Novokuznetsk, Siberia. Photo courtesy of

Rally by Alexei Navalny’s supporters in Novokuznetsk, Siberia. Photo courtesy of