Source: “25 Best Russian Literature Blogs and Websites,” FeedSpot, 4 May 2024

News and views of the other Russia(n)s

Source: “25 Best Russian Literature Blogs and Websites,” FeedSpot, 4 May 2024

Henry Slesar was born in Brooklyn, New York City. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Ukraine, and he had two sisters named Doris and Lillian. After graduating from the School of Industrial Art, he found he had a talent for ad copy and design, which launched his twenty-year career as a copywriter at the age of 17. He was hired right out of school to work for the prominent advertising agency Young & Rubicam.

It has been claimed that the term “coffee break” was coined by Slesar and that he was also the person behind McGraw-Hill’s massively popular “The Man in the Chair” advertising campaign.

Source: “Henry Slesar” (Wikipedia)

The colossal immersive 3D show The Grinch and the New Year Factory

Palma Mansion (18 Pirogov Lane)

Dates: 2.01.2024, 3.01.2024, 4.01.2024, 5.01.2024, 7.01.2024

Time: 11:00, 14:00, 17:00 (daily)

We recommend arriving 30 minutes before the start of the event.

New Year is a magical time of miracles and fairy tales! StageMagic Agency has produced a colossal immersive 3D show, The Grinch and the New Year’s Factory, that will entertain children of all ages and even adults! The show can be seen only from January 2 to 7 in the old Palma Mansion!

This New Year’s week will be full of magic, and even the walls of the mansion will come to life as if by magic! No, no, we’re not kidding! Thanks to cutting-edge 3D mapping technologies we will create a Petersburg Disneyland in an old mansion featuring enchanting sets, an incredibly colorful light show, and an exciting performance, including musical numbers performed by the city’s best artists!

Little viewers can look forward to becoming full-fledged participants in a exciting journey through Cartoonland and along with their favorite Disney characters saving the New Year from the insidious Grinch, who decided to spoil the children’s holiday and stole all the gifts from the elves’ magic factory! Elsa, Jack Sparrow, a wizard on a real magic carpet, and many more will come to the aid of the good elves! Will the cartoon characters manage to save the New Year? Will goodness prevail? Come and find out at the main New Year’s celebration in Petersburg, The Grinch and the New Year Factory.

Before the show starts, children will enjoy an exciting welcome program including interactive games with their favorite cartoon characters, a TikTok show, a beauty bar, a magician’s show, and even a photo shoot with adorable husky dogs.

But that’s not all! Every child will receive a 3D gift from Santa Claus, and every adult will receive a welcome cocktail from the owner of the mansion!

All categories of children’s tickets entitle them to receive a gift.

RECOMMENDED FOR CHILDREN BETWEEN 4 AND 10 YEARS OLD

ADMISSION WITH PARENTS

CHILDREN ARE SEATED IN THE FRONT ROWS BY AGE (YOUNGER CHILDREN IN THE FRONT ROWS, OLDER CHILDREN BEHIND THEM, AND PARENTS BEHIND ALL THE CHILDREN)

There is no such thing as too much magic, StageMagic knows that for sure! See you in the fairy tale!

Duration: 1 hour and 20 minutes

We recommend bringing a change of shoes.

Source: Bileter.ru. Translated by the Russian Reader

Dima Zitser, the well-known educator, writer, and presenter of the weekly program Love Cannot Be Educated, gave a lecture in Berlin in mid-December. Before his “pedagogical standup routine,” as he himself dubs his encounters with audiences, Zitser granted an interview to DW. With Russian schools becoming obedient tools of propaganda, the renowned educator increasingly has to explain to worried parents how to protect their children from the monstrous influence of the government’s lies and manipulation. Zitser told DW how to talk to children about the war, how to teach them to resist propaganda, and how to help them adapt to a new country when they have been forced to move.

DW: Russian parents today often do not know how to talk to their children about the war. They want to protect their children from trauma, but prefer to create an information bubble for them and pretend that nothing is happening. How do you feel about this stance?

Dima Zitser: You cannot avoid talking about the war with your child. You’re forbidden not to talk about it! First of all, it’s tantamount to deception: children are always aware of and know much more about the world around them than we would like them to. If Mom doesn’t talk to it, the child will take its questions to everyone else but Mom. It won’t want to traumatize its mom. It will imagine that this is a painful topic for Mom, that it is not the done thing to talk about it in adult society.

Russian children live in a country that has unleashed a bloodbath. Clearly, we must protect children, and we must choose our words carefully when we talk to them about the subject. But we cannot conceal from them the kind of world they live in. Imagine the level of disenchantment that awaits it when a child bumps its head on this reality. There are no secrets that don’t surface in the end. What do we want our child to grow up to be? A person who doesn’t care about the troubles happening in its midst? It is vital for a person to experience emotional strife.

— Sometimes a child has a hard time coping with the war and even feels ashamed because he or she is Russian. What can parents do in such cases?

You have to explain that it has nothing to do with a people or a nation. Tell your child about the history of Germany, say, which went through its own horror. Tell it about Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht, about people who found the strength to stand out. It was hard for them, but if they hadn’t done what they did, the German people would have been finished.

My eldest daughter lives in New York. She does a lot of projects, including ones on behalf of Ukrainians. Her son Yasha is nine years old. [Ukrainians] refused to speak Russian with them in one place. So Yasha asked, “If this language is so hated and it has to do with this war, why do we even speak it?” There is no short answer in this case. Your conversation with your child should start with the fact that the feelings and emotions of people from Ukraine who cannot stand to hear Russian are understandable.

A close friend of mine from Kyiv refused to communicated me after the Russian invasion started, even though I’ve never been a Russian citizen. But later I wrote to her in Ukrainian (my mom and dad are from Ukraine), and we had the most painful conversation for an hour and a half. We met in Europe a month and a half after the war started, and she explained to me that she couldn’t bear to hear Russian being spoke. Although my friend understands that Russian-speaking people may have nothing to do with the war, she feels physically sick and her body hurts when she hears Russian.

I think we need to talk about it. This is what is meant by empathy. We try to understand, albeit incompletely, what is going on with other people.

— Suppose a child goes to a Russian school where there is aggressive ideological training, where the war is glorified in “Lessons About What Matters.” Is it enough for the family to talk to the child about what is going on?

I take a very rigid stance in this sense. If people who read DW have these things going on at their child’s school, they have to get the child out of there. There is no other option. If we’re talking about a person around six or seven years old, it believes what adults say without a second thought. It has no sense whatsoever that adults could want to harm it. This, by the way, is the basis of many crimes. The impact of school, propaganda, and indoctrination on this person is enormous! There are absolutely horrible studies on this subject in connection with the Second World War and Nazism.

Get the child out of there! In the Russian law on education, there are different forms of education—for example, homeschooling. Right off the bat tomorrow morning, any family can take their child out of school and start homeschooling it. After that, the technical stuff starts. It will be difficult, but did these people assume that they could live during a war and pretend that there was no war? That they could say things to their child at home, and the child would go to its quasi-Nazi school and everything would be fine? It won’t be fine. It’s a war, guys! It’s a matter of saving our loved ones!

We can’t live in a time of war as if it isn’t happening. We have to make decisions. For example, we can form a study group: parents agree amongst themselves, pool their money, and hire a teacher. This is legal, and there is such a trend in Russia.

If a person is fifteen or sixteen years old, it’s no big deal. Well, they will live amidst doublethink, just as we did when we were growing up. True, it did us no good. There is such an argument amongst adults: “We survived after all.” Like hell we survived! We learned to lie, to be mistrustful, to look for a hidden agenda in everything, to expect the worst. I would prefer to live in a world where people are open and frank.

— Suppose a child has been removed from a Russian school, but other sources of aggressive propaganda continue to harass it. Should children be taught to recognize and combat propaganda?

This is like asking whether a person should be taught critical thinking. Yes, of course they should! We should teach them to seek out alternative sources of information and ask follow-up questions. If someone speaks on behalf of the state, one should immediately question what they say. We must teach children that the phrases “everyone knows,” “anyone would say,” and “there is no doubt” are forms of manipulation.

— In addition to children who have remained in the Motherland, there are thousands of children who have left Russia with their parents. The problems faced by emigrants are often discussed, but what happens to the children is forgotten. How should parents behave so that emigration is less painful for their children?

The most common mistake is to try to maintain the routine you had in place before you left the country. Did you study music? You’ll go to music school here too! Were you studying English? You’ll keep learning English! We played chess on Tuesdays? We’ll do the same thing here!

Not even the best parents are immune to this mistake. They instinctively try to maintain stability at such moments, but they are accomplishing just the opposite. The frame of reference has changed! You can’t live in Berlin as if you were still living in Ryazan! People here are different—they speak differently, look different, behave differently. When we try to stop time, we keep the child from growing.

When we keep a child “packed and ready to go,” it has no chance to grow into the country in which it has arrived. What should it do, pretend it’s in Moscow? Not start speaking a new language? Not make new friends? Not go to the German theater? We are suggesting that these years be excised from its life. It’s a grave mistake.

Children are quite protective of adults, often more protective than adults are of them. They understand that Mom has it rough, and Dad has it rough, so I’ll try not to whine. I’m not very good at it—I get prickly and rude—but I try. Adults are really tempted to say, “What do you know about trauma? You’re only nine years old! What we [adults] are going through, now that’s trauma!” But for all its short nine years, it had lived its little life in familiar conditions, from which it was yanked at the snap of someone’s fingers.

You have to find things to keep yourselves afloat. You have to give yourselves the opportunity to learn things, to be interested in things, to like things. There is a beautiful tree here, a comfortable bench here, a nice store here. You have to establish a new routine: going out to eat delicious ice cream after school, inventing new traditions, having new conversations. Yes, it’s going to be hard, and that’s okay. But we’re together, we’re having lots of experiences, we’re recreating our family bonds. If mom (or dad) doesn’t tell the child that she (or he) is having a hard time, then the child is sure that it doesn’t have the right to say that it is having a hard time either. This is an important point! Sometimes, you have to hug each other and cry on each other’s shoulders. This doesn’t lead to neurosis. It’s a way for the child to realize: I’m normal.

Source: Maria Konstantinova, “Dima Zitser: You cannot avoid talking about the war with your child,” Deutsche Welle Russian Service, 20 December 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader

Today, everyone at Samokat is talking about only one thing.

Samokat has been notified that we are being evicted from our little home on Monchegorsk Street in Petersburg. While everyone else is busy with pleasant pre-New Year’s chores, we are being kicked out on the street along with our favorite books and holiday plans. We have just one day to move: tomorrow.

![]() First of all, we appeal to the leadership of St. Petersburg and the Committee for City Property Management. And we hope that the cultural capital is not indifferent to the plight of one of the best bookstores in the city by one of the primary independent children’s publishers in Russia.

First of all, we appeal to the leadership of St. Petersburg and the Committee for City Property Management. And we hope that the cultural capital is not indifferent to the plight of one of the best bookstores in the city by one of the primary independent children’s publishers in Russia.

Just yesterday we shared a Christmas greeting from Natasha, celebrated our publishing house’s anniversary, showed off our cozy annex, and invited you to our New Year’s workshops. Yes, we share all the news with you. Today, unfortunately, there will be no good news.

Samokat’s annex has become a magnet for our dear readers, a place chockablock with warmth and coziness, and we believe that this warmth amounts to much more than four walls (even if they are the four walls dearest to our hearts). Now we need your help very much.

![]() Tomorrow, our little home at Monchegorsk 8B will be open from 9:00 a.m., and we will be giving away all our books at a thirty-percent discount. Now we basically have nowhere to move the books, and any purchases you make will be a huge support to us. Also, if possible, please pick up confirmed internet orders.

Tomorrow, our little home at Monchegorsk 8B will be open from 9:00 a.m., and we will be giving away all our books at a thirty-percent discount. Now we basically have nowhere to move the books, and any purchases you make will be a huge support to us. Also, if possible, please pick up confirmed internet orders.

![]() We are looking for volunteers to help us get our little home ready to move. There are only two young women taking care of our little home, Natasha and Polina, and we are confident that you will not leave them in the lurch. If you are willing to help, come to Monchegorsk from 1:00 p.m.

We are looking for volunteers to help us get our little home ready to move. There are only two young women taking care of our little home, Natasha and Polina, and we are confident that you will not leave them in the lurch. If you are willing to help, come to Monchegorsk from 1:00 p.m.

![]() We are urgently looking for a suitable storage facility to temporarily store our books, we have somewhere around 250 boxes of books, furniture and equipment.

We are urgently looking for a suitable storage facility to temporarily store our books, we have somewhere around 250 boxes of books, furniture and equipment.

![]() And of course, we are looking for a new shelter for our books. We need upwards of 25 square meters for retail space and book events, plus a utility room, in the historical/cultural center of Petersburg.

And of course, we are looking for a new shelter for our books. We need upwards of 25 square meters for retail space and book events, plus a utility room, in the historical/cultural center of Petersburg.

![]() If you have suggestions and options, please write via Telegram at +7 (921) 809-8519, and Natasha and Polina will be in touch.

If you have suggestions and options, please write via Telegram at +7 (921) 809-8519, and Natasha and Polina will be in touch.

Source: Samokat Publishing House (Facebook), 26 December 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader. Thanks to Natalia Vvedenskaya for the heads-up.

1

Since the second phase of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine began on 24 February 2022, there have been heated debates in the press and social media about the extent to which Russian culture—not Soviet culture, but precisely classic Russian culture, starting with the nineteenth century (if not earlier)—is culpable for what has been happening. The accusers say, for example, that all of Russian culture and its leading figures have invariably been infected by the imperialist spirit and the oppression of other countries and cultures. The objections raised against this view can be grouped into several lines of argument. Some opponents say that we shouldn’t ascribe today’s problems to classic writers, while others argue that an entire culture cannot be blamed for this aggression, even if it is supported by the political elite and a considerable portion of society. A third group claims that the Russian officers hurling missiles at civilian settlements or the Russian soldiers looting occupied villages have hardly been immediately influenced by any books whatsoever, so the question of culture’s culpability is entirely irrelevant. Some of the people who object to the notion of a “single and unified” Russian culture hold that those who allege its unity are unwittingly playing into the hands of Kremlin propaganda, which also asserts that Russian culture in its entirety is founded on a “code” and immutable “values,” which the state is supposedly taking great care to uphold by bombing neighboring countries and arresting all dissenters.

I would argue that these debates about culture’s culpability are a psychological trap that takes us back to the early twentieth century, when the humanities were dominated by essentialism—that is, a view of society founded on the absolute certainty that, for example, women and men, or sexual minorities (see Vasily Rozanov’s People of the Moonlight, 1911), or different nations and religions have an immutable essence that predetermines the behavior of individual members of these groups. In the early twentieth century, essentialism was used as an argument in favor of inequality: the “innate characteristics” of women were supposedly such that women should not be allowed to vote, and the “innate characteristics” of colonized peoples were such that they did not deserve the right to self-governance. It is no accident that the twentieth century witnessed the unfolding of two deeply interlinked processes: one social—the fight for the civil and political rights of marginalized groups (feminism, anti-colonialism, queer emancipation), and one in the humanities and sciences that sought to overcome essentialism and affirm the view that the self-consciousness of men and women, the self-consciousness of large cultural or racialized groups, etc., is internally variable and always the result of a long process of historical evolution. Today, we seem to be plunging back down the ladder onto an older rung. As cultural studies scholar Jan Levchenko has astutely noted, Putin’s hostility toward modernity and his rejection of the idea of the future has unleashed an archaization of consciousness in several countries. It is important to resist this process.

A distressing example of the new essentialism can be found in a column published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on 8 September 2023 by the Berlin journalist Nikolai Klimeniouk, titled “Sie wollen, dass wir sie ‘lieben’” (“They want us to ‘love’ them”).[1] Klimeniouk claims that contemporary Russian culture (or all Russian culture? his article does not make this clear) is supposedly founded on the idea of a non-consensual love that does not respect personal boundaries and demands reciprocal “consent” from those nations who were subjected first to Soviet and now to Russian aggression. This belief in the unimportance of other people’s boundaries, Klimeniouk argues, is shared by the intellectuals of Russian descent who defended Andrei Desnitsky, the biblical scholar who was recently fired from Vilnius University following a heated public campaign in the Lithuanian media. The organizers of that campaign took Desnitsky to task for publishing an article in 2012 about the 1940s Soviet occupation of Baltic countries in which he made statements that, in spite of all his caveats at the time, have been read in today’s context as an expression of sympathy for the occupiers.

In his discussion of Desnitsky, Klimeniouk makes an unexpected logical leap. First, he rehashes the viewpoint of the scholar’s supporters:

“The journalist [who wrote about Desnitsky – I.K.] was [not a journalist but] a denouncer. The decision was undemocratic. Desnitsky is an important scholar who brought renown to the university. This would never happen in a civilized country. In Lithuania, they punish you for expressing your opinion, and Russians are hated everywhere.

“This framing is frighteningly similar to a discussion of significance to contemporary Russian culture, which began in 1985 on the pages of the New York Times Book Review, and, it appears, was never concluded.”

Klimeniouk then summarizes two essays which appeared in The New York Times Book Review at that time: “An Introduction to a Variation,” by Milan Kundera, and “Why Milan Kundera is Wrong about Dostoyevsky,” a response by Joseph Brodsky. The turn to this older polemic is symptomatic: Klimeniouk believes that it is possible nowadays to make arguments of the same sort that these two writers exchanged almost forty years ago—although, truth be told, these arguments already sounded quite outmoded even at the time. That’s why it is worth going over these essays in more detail than Klimeniouk provides, since his column revives a debate that already proved unfruitful once.

Milan Kundera’s essay begins with the tale of how, in 1968, a Soviet military patrol stopped him—expelled from all Czechoslovak institutions, his books banned—as he was driving from Prague to Budějovice. The officer in charge tells Kundera, “It’s all a big misunderstanding, but it will straighten itself out. You must realize we love the Czechs. We love you!” This strange declaration of love by an officer of the occupying army makes Kundera recall Dostoyevsky, with his irrationalism and fetishization of strong emotions, as well as Solzhenitsyn, whose Harvard commencement speech criticized the spirit of the European Renaissance. In his essay, Kundera positions himself as a defender of the European cultural values that emerged during the Renaissance: self-consciousness, rationalism, irony, and playfulness.

Joseph Brodsky, already famous in the States but not yet а Nobel Prize winner (that would happen a year after the events described here), took it upon himself to defend Dostoevsky against Kundera on the pages of the New York Times Book Review. However, he also resorted to the same kind of essentialist rhetoric—perhaps to an even greater degree—as his opponent, and to top it off, he also tried to humiliate Kundera, possibly out of sheer irascibility. “[Kundera’s] fear and disgust [toward the occupiers] are understandable, but soldiers never represent culture, let alone a literature – they carry guns, not books. […] Mr. Kundera is a Continental, a European man. These people are seldom capable of seeing themselves from the outside.”

These are more or less the kind of thoughts, according to Klimeniouk, that can be found in the minds of today’s Russian émigré intellectuals, which is why they defend Desnitsky and refuse to entertain the idea of a connection between Russian culture and Russian aggression—they don’t see a link between “guns” and “books” either.

Klimeniouk devotes the rest of his column to a discussion of statements made by Russian writer Maria Golovanivskaya on the topic of love (in an interview with Lev Oborin on the website Polka) and a now-deleted Facebook post by Tatyana Tolstaya (rather unconscionable musings about the rapes of German women by Soviet soldiers). Finally, he quotes a new history textbook for the eleventh grade, written by [former Russian culture minister] Vladimir Medinsky and Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO) rector Anatoly Torkunov, before concluding, “[In contemporary Russia,] high culture has once again lost the battle with state repression.”

This conclusion seems to me both illogical and, perhaps, formulaic: it seems to follow from a different argument than the entire preceding column. In order for culture to “once again [lose] the battle” with the state, there must be a conflict between the two, and Klimeniouk had so far tried to show that there was no conflict whatsoever between Russian culture and the Russian government. What is more, Klimeniouk ascribes to Russian culture “perennial” motifs that can be expressed with equal success using quotes from Brodsky, Golovanivskaya, or Tolstaya. These same “perennial” motifs underlie, in his view, the connection between Russian culture and today’s war of aggression.

It’s not clear whether one should argue with Klimeniouk. This is a scathing newspaper column, published, albeit, in one of Europe’s most influential papers. As for Klimeniouk’s attack on Desnitsky, the composer Boris Filanovsky has already offered an excellent response on his Facebook page. Is there anything we must add to his objections?

I think that we should analyze the psychological stance underlying Klimeniouk’s article. These days, this approach threatens to spread much farther than a single newspaper article, and not just in the media, but also in scholarship. This is precisely why I think that what matters now is not whether Klimeniouk is interpreting Brodsky correctly, or even what all this has to do with Andrei Desnitsky getting fired. What matters is methodology. How can we contextualize and explain this rhetoric of “love” that Klimeniouk apparently considers something akin to an incurable (or, at any rate, intractable) disease of Russian culture?

2

A newspaper column certainly has its own generic rules: it is meant to quickly convince readers that the author is right. Nevertheless, even taking these rules into account, it is surprising that Klimeniouk does not bring in several rather obvious nineteenth-century texts in which the “love” rhetoric he describes is most effectively expressed. Looking at these texts, however, makes it clear that this rhetoric is an expression of a specific historical-evolutionary line that can be traced to the mid-nineteenth century, rather than reflecting universally shared qualities of Russian culture. This line could be called expansionist universalism. The texts created within its framework became a crucial intellectual resource that facilitated the emergence of the Russian state’s current rhetoric of war—but not as texts per se, but because this rhetoric was later substantially reworked by late-Soviet Russian nationalists.[2]

The first example is Fyodor Tyutchev’s poem “Two Unities” [“Dva edinstva,” September 1870). Addressed to the “Slavic world” (the same sort of ideological construct as the “Russian world” is in our time), with its famous second stanza pointing to Otto von Bismarck as the “oracle of our day”:

«Единство, — возвестил оракул наших дней, —

Быть может спаяно железом лишь и кровью…»

Но мы попробуем спаять его любовью, —

А там увидим, что прочней…

“Unity,” declared the oracle of our day,

“Can be forged solely through iron and blood.”

But we shall bond our unity through love,

And then we shall see which of the bonds gives way.

Tyutchev called for the creation of a Slavic federation led by Russia, which was to be founded on “love.” The famous Czech poet and journalist Karel Havlíček Borovský (1821–1856) once wrote about this “love”: “Russians call everything Russian Slavic in order to later call everything Slavic Russian.” But Havlíček did not mean all Russians when he said “Russians”; he meant the Slavophiles, who were unwittingly playing along with their government. And, while Havlíček criticized the Slavophiles and the Russian state’s autocracy, he also translated Gogol and Lermontov into Czech.

The second example is Dostoyevsky’s “Pushkin Speech,” delivered in 1880. It declares love as the basis of the Russian people’s “world-scale kind-heartedness”:

«…Мы [русские] разом устремились <…> к самому жизненному воссоединению, к единению всечеловеческому! Мы не враждебно (как, казалось, должно бы было случиться), а дружественно, с полною любовию приняли в душу нашу гении чужих наций, всех вместе, не делая преимущественных племенных различий, умея инстинктом, почти с самого первого шагу различать, снимать противоречия, извинять и примирять различия, и тем уже выказали готовность и наклонность нашу, нам самим только что объявившуюся и сказавшуюся, ко всеобщему общечеловеческому воссоединению со всеми племенами великого арийского рода…»

“Indeed, we [Russians] then impetuously applied ourselves to the most vital universal pan-humanist fellowship! Not in a spirit of enmity (as one might have expected) but in friendliness and perfect love, we received into our soul the genius of foreign nations, all equally, without preference of race, able by instinct from almost the very first step to discern, to discount distinctions, to excuse and reconcile them. Therein we already showed what had only just become manifest to us—our readiness and inclination for a common and universal union with all the races of the great Aryan family.”

The third example is Alexander Blok’s poem “The Scythians” (1918), which literary scholars have noted was directly influenced by the “Pushkin Speech”:

Да, так любить, как любит наша кровь,

Никто из вас давно не любит!

Забыли вы, что в мире есть любовь,

Которая и жжет, и губит!

Мы любим все — и жар холодных числ,

И дар божественных видений,

Нам внятно все — и острый галльский смысл,

И сумрачный германский гений…

Yes, to love the way that our blood loves,

None of you has loved in countless years!

You have forgotten that there is a love

That burns and wrecks and wakens fears!

We love it all—the sear of ice-cold numbers,

The gift of divine illuminations,

We grasp it all—the sharp-edged Gallic wit,

The gloomy genius of the Germans.

The version of universalism on which Tyutchev, Dostoyevsky, and Blok insisted assumed that practitioners of Russian culture, who had arrived late to the dialogue of European culture(s), could occupy a central place in that dialogue because they (speaking as it were on behalf of “Russians”) could allegedly understand everything, and this ability to understand was underpinned by the unique Russian capacity for “love.” Mastering a foreign culture, as based on this universal “love,” becomes a form of self-affirmation for the “lover.” This rhetoric was a means of alleviating and masking the constant tension between two images of Russia produced in the press and in government publications, a tension felt ever more strongly over the course of the nineteenth century: Russia as the nation-state of Russians and Russia as a multi-ethnic empire. But this task of “all-conquering love” was not declared on behalf of the government, but rather on behalf of society. While the “we” in Tyutchev’s poem could still encompass the and society, in Dostoyevsky’s speech and Blok’s poem the “we” points first and foremost to a society that was ready, in their opinion, to bring about cultural expansion in place of the state.

Some of their contemporaries sharply criticized this rhetoric. For example, the well-known critic Nikolai Mikhailovsky noted very soon after the publication of the “Pushkin Speech” that Dostoyevsky’s calls for a “united Aryan tribe” had anti-Semitic undertones.

If we examine the examples given by Klimeniouk with a view to older history, it becomes clear that the Russian intelligentsia’s universalism has not always and across the board had an expansionist character. There have been at least two variations. The first is westernizing, which assumes that Russian culture is too archaic and that it can and must be renewed with the help of transfers of Western European culture into Russia. This thinking was, for instance, foundational for the translation strategy of the Russian Symbolists, who were able in the 1900s and 1910s to “catch up” to French poetry, which was developing rapidly at the time. This westernizing conception influenced the program of the World Literature publishing house, founded by Maxim Gorky in 1919. At a different historical stage, westernizing universalism manifested itself in a passion for Polish culture (jazz, poetry, fashion magazines) among the nonconformist intelligentsia in the 1950s-1960s; Brodsky himself was a Polonophile in his youth. Of course, Thaw-era Soviet Polonomania was rarely marked by a deep interest in the other; it was often just the urge to imagine an alternative, better life for oneself, but cultural transfers often occur in exactly this fashion.

The second, rarer variation is philanthropic, whereby the popularization of different cultures in Russia served to express sympathy and moral support for the bearers of said culture(s). In 1916, immediately following the Armenian (and Assyrian) genocide in the Ottoman Empire, an enormous book of translations entitled The Poetry of Armenia from Ancient Times to the Present Day was published under the editorship of the prominent poet and critic Valery Briusov. The translators included other well-known poets such as Jurgis Baltrušaitis, Konstantin Balmont, Ivan Bunin, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Vladislav Khodasevich—and even Alexander Blok, author of “The Scythians.” The anthology did not have colonial or expansionist intentions, however; instead, it voiced Russian civil society’s solidarity with a people subjected to genocide (even though that word didn’t even exist yet). Briusov took on direction of the project only after he gave himself a crash course in basic Armenian and read several books about the history of Armenian literature.

The anthology was the first in a series of translated compendiums of ethnic minority literatures of the Russian Empire, for whom the catastrophes of the First World War were particularly hard. These anthologies were of major philanthropic significance and were edited by Briusov, Maxim Gorky, and several other Russian writers. They included An Anthology of Armenian Literature (Sbornik armianskoi literatury, Petrograd: Parus, 1916, edited by Gorky); An Anthology of Latvian Literature (Sbornik latyshskoi literatury, Petrograd: Parus, 1916, edited by Briusov and Gorky); and An Anthology of Finnish Literature (Sbornik finliandskoi literatury, Petrograd: Parus, 1917, edited by Briusov and Gorky). Adjoining them is an anthology of translations from then-contemporary Hebrew poetry, The Jewish Anthology, published in 1918 by the Moscow publishing house Safrut, and edited by Khodasevich and Leib Yaffe.

In the Soviet context, beginning in the mid-1930s when Stalin veered into isolationism and “Russocentrism” (David Brandenberger’s term), universalism became a stealth-oppositional attitude. It expressed—to use Osip Mandelstam’s coinage—a longing for the world culture beyond the “iron curtain,” and was a way of resisting the notion of Russian culture as something absolute, self-important, and completely adapted to Soviet conditions. There was a reason why in late Stalinism any attempts to study the influence of Western literary traditions on Russian literature were subject to persecution. Research of this sort was stigmatized as “cosmopolitanism” and “kowtowing to the West.”

In the late Soviet period, there was an official universalism in which the rhetoric of “love” à la Tyutchev or Dostoyevsky was invoked only rarely, but which reproduced a construction typical of their texts: “the primacy of the one who loves.” The Russian people were to be understood as an “elder brother” implicitly united with the Soviet state (“The unbreakable Union of free republics / was bound all together by Great Rus,” as the first line of the Soviet national anthem declared).[3] This Soviet official universalism appears to be exactly what the officer whom Kundera encountered was relaying: “we” love “you,” the Czech people, and this is exactly why we saved you from the Prague Spring, from the “pernicious” desire to live as you wish. And this paternalistic, protective, colonialist universalism, ramped up into a sort of cargo cult (“we will repeat what was said then—and it will be as it was then”) is replicated by Margarita Simonyan in one of her tweets (13 July 2023), in which she writes:

“What did you not like about living with us? What was so bad about it? Most of you have us to thank for statehood, you got culture thanks to us. Who was oppressing you? Who messed with you?”

This Soviet version of universalism is exactly what today’s stylistics of “re-enactment” has been replicating, and it is one of the intellectual resources driving Russia’s war against Ukraine. The people who have written and write in this tradition can certainly be held responsible for what is happening today. But there are other forms of universalism that have been preserved and survive in Russian culture. Understanding universalism as a complex, evolving discursive system containing many variations makes it possible to look at Russian culture not as a single, unified, and timeless whole invested with a unified, singular culpability, but as a space open to polemics in which different ideas grapple with each other.

3

Let me move on from the discussion of the varieties of universalism to more general thoughts on the methodology of the contemporary humanities and social sciences. They might seem trivial to my colleagues in history, but over the last year and a half these basic tenets of the profession have seemingly been overshadowed, and it would behoove us to recall them.

A historian is not required to forgive or rehabilitate the figures they write about, but it is important to understand these figures within the context of their own time—what they could or could not think about, what concepts they used, what kind of knowledge or resources were available to their characters, or to whose questions they were responding. This paradigm of historical knowledge was established by the French historians of the Annales school and further developed by the intellectual historians of the Cambridge school—e.g., John Pocock and Quentin Skinner.

Proponents of historicism are sometimes accused of enabling relativism: general rules do not exist; each era has its own norms. Still, the example of late-Soviet humanities scholars—of figures such as Sergei Averintsev, Aron Gurevich, and Mikhail Gasparov—shows that they did not think of historicism as a branch of relativism but as a tool for understanding people from different eras and cultures, and this work of understanding (especially for Gasparov) enabled them to grasp the limitations of the cultural conventions of their own time. They developed their concepts of historicizing interpretation as a tool for understanding over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, and this approach was one of the most significant advances in the late-Soviet humanities and social sciences in terms of both its scholarly and existential utility.

This interpretative sequence—understanding the other so as to better understand one’s own situation and, by reflecting on one’s own situation, gaining an even more accurate understanding of the other—was laid out by proponents of the philosophical school of hermeneutics. Yet neither the hermeneutic philosophers (Paul Ricœur and Hans-Georg Gadamеr) nor the unofficial Soviet humanities scholars directly inquired into the consciousness of an interpreter belonging to a repressed or silenced societal group (even though unofficial humanities scholars in the USSR certainly belonged to such a group), or to one identifying their own sense of self with those in an unprivileged position. (Yuri Lotman’s persistent discussion of the history of the Russian intelligentsia as a stigmatized and marginal group shows that he understood the position from which he was speaking quite well.) In hermeneutics, the interpreter of the world appears as a kind of “default subject” (implicitly, a white European man), so it may seem as if hermeneutics were at odds with critical theory and its closely affiliated approaches—feminism, postcolonial and decolonial theory, queer studies. But the current intellectual state of affairs shows that these approaches can be synthesized.

Critical theory teaches researchers to ask themselves questions—and not just about their own privilege (“check your privilege”), but also about the conceptual tools they are using. For example, I myself should consider whether my mind retains the traces, the discursive debris, of the expansionist universalism which I discussed earlier.

Today, when we talk about history as the result of human efforts with specific social, discursive, and conceptual parameters, feminist, queer, postcolonial and decolonial theory all help to focus our gaze more sharply. But these methods could also benefit from the acuity afforded by historicism, because the human conflicts and interactions they study have differed in different eras and took on a particular shape in each specific instance. Now, let’s turn to why this kind of synthesis is necessary.

In 2011, Stanislav Lvovsky wrote that, sooner or later, Russian culture would have to be reconstituted on new foundations. It is now obvious that he was right. When undertaking this project, it will be important to take stock of the resources available to сultural professionals in their fight against the tendencies that Russia’s leaders have let proliferate and become dominant—no matter how many states emerge out of the ruins of today’s regime at the end of the current political cycle. I think that if we examine the different versions of Russian universalism historically, using the methods developed by the Annales school, we will find that, alongside the passive-aggressive tradition observed by Kundera, Russian culture also has resources for resisting the state’s rhetoric of “paternalistic love.” These resources are primarily found in works of unofficial literature and unofficial scholarship.

I dearly hope that Ukraine wins this war, but a mere military victory would not be enough for me. At the end of the Second World War, scholars in different countries set to thinking up ways to undermine the intellectual foundations that gave rise to Nazism. (Many years after the war, Michel Foucault’s foreword to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus called the book “an introduction to non-fascist life.”) Today, people in many different countries also have reason to think about how they can subvert the intellectual foundations which are producing an aggressive right-wing populism that stigmatizes minorities. When right-wing populism is implemented by former security-service officers gripped by ressentiment, you get the nightmare that is playing out in Russia today.

I think that the future of humanity lies not in national but post-national states—societies organized as federations of different minorities. The methodology of the contemporary humanities and social sciences can function both as a common language that different minority groups can use for collective action, and as a crucial tool for understanding the other, and others.

Source: Ilya Kukulin, “Dostoyevsky, Kundera, and the culpability of Russian culture,” Colta.ru, 11 September 2023. Translated by Ainsley Morse and Maria Vassileva. I am grateful to them for their fine translation, and to Mr. Kukulin for his permission to publish it here. ||| TRR

[1] The excerpts from Klimeniouk’s article quoted here were first translated from the original German into Russian by the author himself, and then rendered in English by the translators.

[2] See, for instance, the uncensored version of Stanislav Kunyaev’s poem “Okinu vzgliadom Severo-Vostok,” [“I will cast a gaze at the North-East”], which was first published in 1986: “Let the Mansy salute Yermak, / And it is meet for the Uzbek to praise Skobelev, / for the fact that we now have gas and timber and cotton, / and have room for lots of missiles.”

[3] Text by Sergei Mikhalkov and Gabriel El-Registan.

I read on social media yesterday that Russian ebook giant LitRes had added a button on its website for readers who want to file a complaint against any of the books it offers for violating Russian laws. To see whether this was true, I punched up the most popular recent Russian book among readers of this website, Katerina Silvanova and Elena Malisova’s runaway LGBTQ+ romance bestseller A Summer in a Young Pioneer’s Tie.

Indeed, there is such a button, located below the book’s description and right next to a summary of its front matter. In the screenshot I took, above, I’ve drawn a black box around the button, which reads, “Does the book violate the law? Complain about the book.”

If you do the unthinkable and press the button, a window pops up:

“What do you want to complain about?” the prompt asks. The choices are “Promotion of narcotics,” “Promotion of suicide,” “Violence/extremism,” “Copyright violation,” and “Promotion of LGBT and/or Pedophilia.” You are then asked to “describe the violation” in 1,500 characters or less and dispatch your complaint to LitRes’s law-abiding overlords by hitting the big orange-red “Complain” button.

A quick scan of the 113 titles in my own “bookshelf” on LitRes and some of the book’s suggested to me by the service revealed, however, that readers cannot file a complaint against any book they wish. Anna Akhmatova’s Requiem, for example, is beyond suspicion, as you can see in the screenshot, below. ||| TRR

This is the fantasy:

At a pinch he could do the same in French, but French specialists were two a penny, and, in any case, Russian was his thing. He loved the Cyrillic alphabet, the byzantine grammar, the soporific, sensuous sound of the Russian language. And once, he had loved a Russian woman.

[…]

“Let’s get some sleep,” said Hyde. “Tomorrow… sorry, make that today, you need to be on top form. The briefing book is right here.” Hyde tapped the file on the table. “Are you up to speed on the current jargon? Post-truth and alternative facts and all of that? What’s fake news in Russian?”

“Feykoviye novosti,” Clive said without missing a beat. “But the purists are up in arms. Feykoviye is not a Russian word. It’s an anglicization. They think it should be lozhniye novosti. Lying news.”

[…]

Then he focused on the job in hand. The mental preparation was always the same, a limbering up of the mind, a rigorous testing of himself. He went through various linguistic exercises, tossing English words and phrases into the air like tennis balls, then hitting them across the net in Russian. It was natural, effortless; he felt completely at ease in either language.

[…]

“Clive was member of our Russian book club on the fourteenth floor of the UN,” Marina said, looking at Hyde.

“I was,” said Clive, looking straight at Marina and taking in every detail of a face he had done his best to forget for over a decade. He had also forgotten the particular musicality of her English, which gave her away as a foreigner. Now and then her “o” was slightly too long and her “r” was a little too hard, and sooner or later she would forget an article,* just as she had a moment ago. Her English was almost perfect. But not quite. It was all part of her infinite charm.

[…]

“Alexei had this thing about grammar. Said I had to speak clean Russian. Clean… That was his pet word. ‘Use the instrumental and not the fucking accusative.’”

[…]

After making love, they would lie in bed and smoke and talk about their favourite writers. They showed off to each other, Marina reciting Pushkin, Clive quoting Shakespeare, and then vice versa, switching effortlessly from English to Russian and back again. They chucked proverbs and abstruse words at each other until they dissolved in laughter.

Source: Harriet Crawley, The Translator (London: Bitter Lemon Press, 2023). Cover image courtesy of Bitter Lemon Press

* But check out the abuse and misuse of articles on display here, of all places:

HARRIET CRAWLEY, “THE TRANSLATOR”. IN CONVERSATION WITH SIR RODRIC BRAITHWAITE

- Tuesday, 2 May 2023, 7:00 pm —8:30 pm

- 5a Bloomsbury Square, London, WC1A 2TA, United Kingdom

Join us to hear Harriet Crawley discuss her latest novel, a love story and political thriller, with the former British ambassador to Russia, Sir Rodric Braithwaite. The Times has included The Translator in its list of “the best new thrillers”, and the reviews praise author’s descriptions of the everyday life in Moscow, her ability to create suspense, and the political relevance of the plot at the time when the Russian state has once again become a major geopolitical threat.

[…]

The Translator tells a story of two interpreters, one British and one Russian, who embark on a quest to protect vital communication infrastructure connecting the UK and the US from sabotage by Russian special operations forces.

Source: Pushkin House. The emphasis is mine. ||| TRR

While this is a bit closer to the often harsh reality:

Kill the Translator: A Song of Inadequacy

He’s the mad dog of letters, the scrivener of sin.

He stays up nights with dictionaries and gin.

He studies Icelandic with a six-fingered Finn.

He’s the translator.

He trampled your iambs, desecrated your prose.

He mangled your message and stepped on your toes.

His syntax is suspect, his Swahili a pose.

Maim the translator.

Your essay’s in tatters, your short story in ruins.

He rendered 'tomato' as 'the mating of loons'.

And tomorrow he’ll english your poem out of tune.

Harm the translator.

It matters quite little whether he’s stout, thin, or black,

Venetian, Guatemalan, or from Hackensack:

Send him Derrida by mail, and an ounce of crack.

Suicide the translator.

Stop the presses in Cape Town and summon the cops.

Make a pass at his mother, toss a spear at his pop.

And dare he protest, quote him Lacan till he drops.

Crush the translator.

Rip his Oxford to shreds, set his grammars on fire.

Break all his pencils, call Nabokov a liar.

Instead of advances, blow him curses by wire.

Unhinge the translator.

He’s a cheat and a fraud and the foe of good sense.

Promise him the heavens, but repay him in pence.

'Traduttore traditore,' they say, and hence:

Kill the translator.

Source: The Russian Reader, St. Petersburg, October 1996. The poem was inspired by an incident (one of dozens) in my early career when I was paid a pittance to translate the catalogue for a show of contemporary Russian art in Finland. A few months later, I got a notice from the Finnish tax authority which made it plain that, officially at least, I had been paid several times that amount by the host museum, but the Russian curators had pocketed the difference, thinking I would be none the wiser.

If you don’t want this website and its free, unique, eye-opening content to be maimed, harmed, crushed, suicided, killed, or unhinged, show your support today by liking, commenting, sharing, or donating (via Stripe or PayPal — you’ll find the forms and links in the sidebar). It’s vital for me to know that there are actual people out there who value my unpaid labor of love, which is now in the midst of its sixteenth year. I’ve received only $137 in donations so far this year, alas. That’s not enough financial support for me for to keep doing this much longer, considering that last year, for example, my overhead costs alone were $1,620 (for internet, hosting, and online subscriptions), against only $1,403 in donations for the entire year. ||| TRR

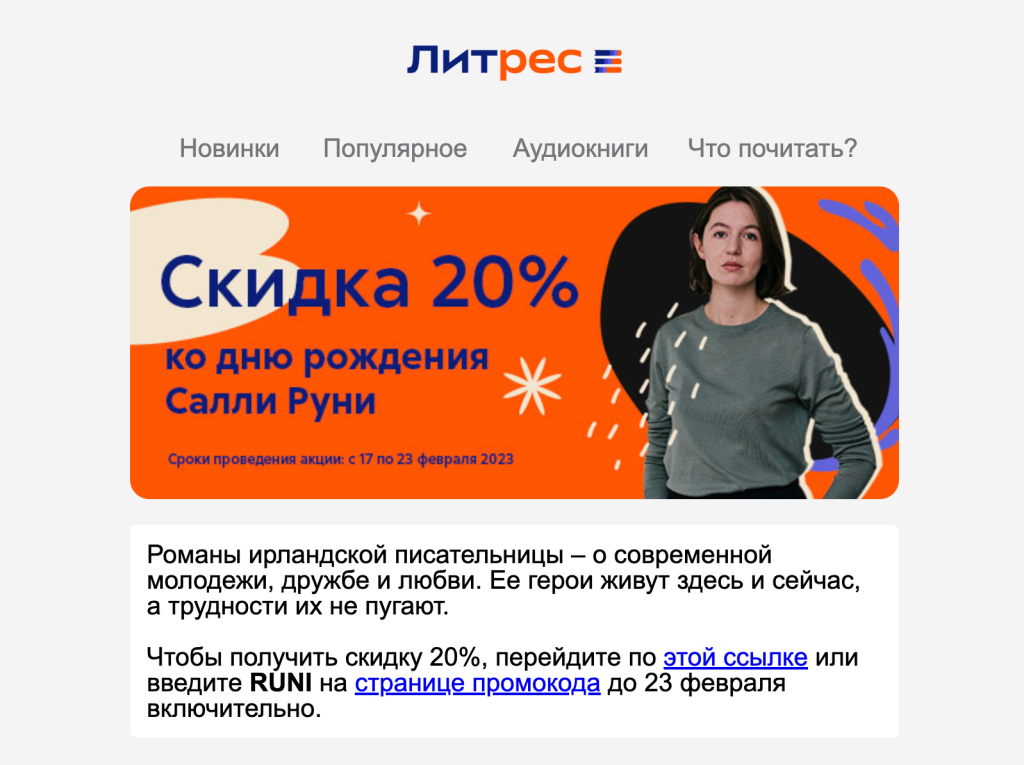

A 20% discount for Sally Rooney’s birthday.

The promotional campaign runs from 17 to 23 February 2023.

The novels of the Irish writer are about modern youth, friendship and love. Her characters live here and now, and difficulties do not frighten them.

To get a 20% discount, follow this link or enter RUNI on the promo code page by February 23.

Source: Litres newsletter, 20 February 2023. Translated by TRR

A city of contrasts. Moscow, 2023

Source: Igor Stomakhin (Facebook), 20 February 2023. Picture caption by TRR

“MANUSCRIPTS DON’T BURN” FUNDRAISING CAMPAIGN TO SUPPORT STUDENTS FROM UKRAINE, BELARUS, AND RUSSIA AFFECTED BY WAR OR PERSECUTION

Tamizdat Project Inc. is launching a two-month campaign “Manuscripts Don’t Burn” to support undergraduate students forced to leave their home countries due to Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine or persecution in Belarus and Russia for their anti-war stance.

“On the last day of 2022, as we all were getting ready to celebrate the arrival of the new year the Russian missile attack hit Kyiv, causing serious damage to the buildings and properties of the Kyiv University. … It had become the worst year for the higher education since the end of World War II. Any assistance we can provide for students of Ukraine will be greatly appreciated by the students in the universities under fire and the students-refugees in Ukraine and abroad.” — Serhii Plokhy, professor of Ukrainian history, Harvard University

“I am glad to take part in this project. After all, the auction that Tamizdat Project has put together is not just about rare books that make any library more precious and interesting. It is also part of the living history of free literature and thought, uninterrupted even today. These books, as dissidents used to say, are relics of the struggle ‘for our freedom and yours.’ They unite authors and readers, turning even those unfamiliar with each other into allies.” — Alexander Genis, author

Tamizdat Project is a not-for-profit public scholarship and charity initiative devoted to the study of banned books from the former Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War (“tamizdat” means literally “published over there,” that is, abroad). Today, these books remind us that freedom and education know no boundaries. We are a not-for-profit 501(c)3 organization with a tax-exempt status: donations and gifts are deductible to the extent allowable by the IRS.

Contact: Yasha Klots • Tamizdat Project Inc. • tamizdatproject@gmail.com

In One Hundred Years (A New Year’s Fantasy)

On the eve of the new year of 2023, the Great Worldwide Soviet Republic communicated by radio with the nearest republic on the planet of Mars, inviting delegates from the latter to a celebration and receiving, in turn, an invitation from the Martian Republic.

Earth assigned a total of 415,000 delegates from its five parts, while Mars assigned 630,000 delegates from its seven parts. The delegates boarded airplane trains and headed to the celebration.

The airplane trains took 19 hours and 17 minutes to travel between Earth and Mars.

Earth was lit up for the occasion by the electro-sun invented in 1994 by the electro-engineer Makov, a peasant from the current Kaluga Province in the Russian District. Besides lighting Earth, Makov’s electro-sun gave off heat, but not the intolerable kind, like the real sun did. The electro-sun’s heat was considerably milder, and its light also emitted an unusual aroma that combined all the world’s fragrances.

The Martian comrades were welcomed with music by the World Orchestra via a gramophone organ that transmitted melodies over any distance at the same volume, so the music was as audible on Mars and the other planets as it was on Earth.

After the neighboring planet’s delegation was welcomed, the festivities commenced.

________

On New Year’s Day 2023, the inhabitants of the two planets were to be dazzled by all the beautiful, magnificent and beyond marvelous things wrought by the collective mind and millions of hands of their creators.

The celebration on Earth was kicked off by a 137-year-old citizen of Petersburg, the worker Prokhorov, a contemporary of Lenin and Trotsky, the founders of the Russian Republic and of the Worldwide Republic that succeeded it. Despite his advanced age, this last Mohican of the RSFSR looked like a young man of 18 years since in that time old age was cured, so to speak, like a garden-variety headache. Thanks to Doctor Patokin’s pills, which had vanquished aging, the residents of Earth in the aforementioned era had the appearance of splendid, strapping youngsters. Death was a quite rare phenomenon: the newspapers reported as an intolerable circumstance that should have no place in the happy Republic.

When Prokhorov took the podium, which was surrounded by mirrors that broadcast the speaker’s reflection to all corners of Earth and Mars, he spoke into a loudspeaker of his own invention. It amplified the sound of the voice such that it could be heard over any distance. (Prokhorov had also invented the gramophone organ mentioned above.)

Prokhorov spoke in detail about the emergence of the First Soviet Socialist Republic, and his account was illustrated by a movie projector whose screen was the sky.

All the events between 1917 and 2023 passed before the eyes of the spectators.

One of them, a 14-year-old citizen, pointed to the moving images and asked his father, who was standing next to him:

“Dad, how tall were people then?”

“People your age were half your size, while adults, on average, would have come up to your shoulder, if they weren’t shorter,” his father replied.

“Poor things,” said the 14-year-old citizen with sincere pity. In terms of height and build, he resembled our undefeated wrestler [Ivan] Poddubny (although he had an ordinary figure for a boy in the year 2023).

The boy grew pensive and sighed deeply.

“Why were they so tiny and weak?” he asked mournfully.

“They had begun living the right way only in 1917 and, at first, only here in Russia. And they had a bad diet — they just ate bread and meat, I think.”

“But didn’t they have life wafers?” the son continued.

“No.”

“And they didn’t have strength and health extract either?”

“No, they didn’t have them either.”

The boy again felt sorry for them.

“Poor things,” he said, adding, “My school comrade Petya Kominternov told me that at the Antiquities Museum he once saw a men’s shoe from back then that he could get only three toes into, leaving half his foot uncovered. Only this one 5-year-old boy was barely able to put the shoe on. So it’s true?”

“It certainly is,” the father confirmed, adding, “But if it hadn’t been for those feeble-bodied but strong-willed tiny people, then we wouldn’t be so tall and strong, so free and happy, and you wouldn’t see the splendid things you’ll see today.”

________

After listening to Prokhorov’s reminiscences, the father and son headed to the fair, where an exhibition of various innovations had commenced. The unusual number of improvements and new inventions that were made each year was achieved through the free collective labor and creativity of the Great Worldwide Republic’s happy inhabitants.

You name it, it was there. In full view of the public, truck farmers grew various unusually delicious vegetables in five minutes using a newly developed fertilizer, while flower gardeners, as if they were fairytale wizards, cultivated tropical plants on the Square of the Victims of the Revolution in a matter of 15 to 20 minutes. The unceasing sounds of the Petersburger Prokhorov’s gramophone organ complemented an endless, dazzling New Year’s fireworks display, which depicted the events of 1917–1923 — congresses of Soviets, wars, and revolutions — in a series of fiery tableaux. The expositions of technological and mechanical marvels alternated with works of art. A women’s, men’s and children’s beauty pageant provoked merry laughter among participants and spectators alike, for there were no homely people and there was thus no one on whom the prize could be bestowed — all of them were extraordinarily beautiful.

But the highlight of the festivities was an experiment carried out by a group of scientists from Earth and Mars that consisted in mutually attracting the said planets by means of devices that the said scientists had invented. The devices released the appropriate gas from each of the planets, causing them to alter their orbits (their motion through the void of space) and bringing them quite close to each other.

The audience’s delight knew no bounds.

The 14-year-old citizen sat up pensively for a long while after going to bed that night.

“Why aren’t you sleeping, dear?” his father asked tenderly.

“Dad,” the boy said thoughtfully, “how good it would be if Comrade Lenin were alive now.”

“My dear son,” said the father, his voice trembling with tearful, tender emotion, “Lenin is alive. Lenin is immortal. He is part of everything you saw today. Sleep, my boy. Lenin is alive and will never die. Can dynamics or electrification die? No, they can’t. Isn’t Lenin the sum of all of those things? He is everything.”

The starry night quietly descended on January 2, 2023.

The 14-year-old citizen sleeps. He dreams of the Progenitor of worldwide happiness and freedom, the short, stout man in suit and cap, with intelligent, penetrating eyes and the good-natured, sly smile on his lips known to the entire universe.

The boy smiles in his sleep.

“Dear comrade Lenin. Dear Ilyich. Good Ilyich, kind… dear Ilyich…”

Vasily Andreyev

Source: Krasnaya Zvezda 254 (299), 31 December 1922–1 January 1923, p. 3. Thanks to Szarapow for unearthing and sharing this gem. Translated by the Russian Reader

Vasily Mikhailovich Andreyev (December 28 (January 9), 1889—October 1, 1942) was a Russian Soviet prose writer, playwright, journalist, and exponent of “ornamental” prose in literature. In the 1940s he was repressed.

He was born in St. Petersburg to the family of a bank teller. His mother was a homemaker. He graduated from a four-grade municipal school. In his youth, he was involved in the revolutionary movement. In 1910, he was convicted of murdering a gendarme (according to the writer’s daughter: “he was covering someone handing out revolutionary leaflets”). From 1910 to 1913 he was exiled in the Turukhansk Region, whence he fled. According to some reports, he helped arrange Stalin’s escape. He was amnestied in connection with the celebration of House of Romanov’s 300th anniversary.

He began publishing in 1916 in newspapers under the pseudonyms Andrei Sunny, Vaska the Newspaperman, Vaska the Editor, etc. Until 1917, he mainly lived in Ligovo, but after the October Revolution he returned to Petrograd and became a professional writer. In the late 1920s, in a letter to S.N. Sergeyev-Tsensky, Maxim Gorky spoke of Andreyev as a writer who was “not susceptible to Americanization.”

A talented writer on social themes who suffered from binge drinking and dearly loved his sickly daughter, there was nothing but a cot and an office desk in his room, and he carried in his empty, beat-up wallet a certificate stating that he had shot a policeman in such-and-such pre-revolutionary year.

[…]

On August 27, 1941, Andreyev left his house and did not return. As transpired later, in response to a query sent to the KGB by the literary critic Vladimir Bakhtin, Andreyev had been arrested by the Leningrad Regional NKVD. He was charged under Article 58-10 of the RSFSR Criminal Code (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda”). He was later transferred to the city of Mariinsk, Novosibirsk Region, where he died on October 1, 1942, of “cardiac arrest due to beriberi.”

He was exonerated on January 23, 2001.

[…]

Source: Wikipedia. Translated by TRR

More than 200 thousand copies have been sold — an absolute bestseller. Its authors, Katerina Silvanova and Elena Malisova, did not expect the novel to take off. In 2021, one of the readers of A Summer in a Young Pioneer’s Tie made a TikTok based on the book that went viral. “We had a wild number of views — it was surreal,” recalls Katya. A month after its publication, homophobes drew attention to the book: threats to imprison, rape, kill, burn, and drown the authors along with their novel rained down on social networks. By the end of this summer, the scandal around LVPG [as the novel is known to fans] had ballooned to calls to remove the book from stores, while politicians in the regions went so far as to burn copies of the book. Russia has now adopted the most scandalous law of recent years — a complete ban on LGBT propaganda [see below]. A Summer in a Young Pioneer’s Tie has again been cited by officials as the [negative] “gold standard”: this is what has been target by the state’s hatred.

Who are Katerina Silvanova and Elena Malisova? Where are they from? How did they become writers? How did they manage to write the year’s biggest book? Special to The Village, journalist Anya Kuznetsova traced their real-life stories from childhood to the present day.

In brief: what is the book itself about?

The plot centers around the relationship between two young men — Young Pioneer Yura and camp counselor Volodya. They meet at the Ukrainian summer camp Swallow in 1986, forming a friendship that eventually blossoms into a teenage romance. It is difficult for the characters to accept their homosexuality. Volodya suffers from internal homophobia and worries that he is “seducing” the Young Pioneer, while Yura does not understand what his lover feels and tries to conceal his affection.

The authors of the novel raise topics that are sticky in post-Soviet society: the stigmatization of LGBT people, the inability to openly build relationships, and the need to constantly ensure that they are not disclosed. This is clearly seen in the episode when one of the Young Pioneers, Masha, tries to report Yura and Volodya’s relationship to the authorities, which may threaten the counselor with expulsion from university.

Another feature of this text is a style typical of fan fiction. Using a simple, accessible language, Elena and Katerina have created a text unique in Russophone literature. Yes, the topic of same-sex love has been raised before — for example, by the poets Mikhail Kuzmin and Sofia Parnok — and critics have detected homoerotic motifs even in the fiction of Gogol and Tolstoy. But the authors of LVPG have been, perhaps, the first to succeed in producing a genuinely popular Russian-language text directly describing a romantic relationship between men — so much so that it has been banned.

A year later, in the midst of the hype around LVPG, Popcorn Books published a sequel to the novel, What the Swallow Won’t Say (aka OCHML). The events in the new novel unfold twenty years after Yura and Volodya parted: they never managed to meet again after their time at summer camp.

The characters are now adults, living their own lives. Volodya runs his father’s construction company and is in an abusive relationship with a married man, while Yura has moved to Germany and writes music. They accidentally meet again and try to build a relationship, but it’s not so simple. Yura suffers from writer’s block and alcoholism, while Volodya suffers from self-harm and controlling behavior.

Although OCHML continues the plot line started in LVPG, the book is anything but an easy read: the authors delve deeper into the stigmatization of the LGBT community, while simultaneously exploring addiction, abuse, violence, and conversion therapy. You can read more about the second part in Bolshoi Gorod.

Part 1. Lena Malisova’s story: Childhood at a sawmill, abuse, and the death of her father

Kirov in the 1990s is where the future writer grew up. Lena’s parents owned a sawmill in the village of Suzum (Kirov Region) and took their daughter with them, says Malisova.

“The sawmill was in the forest, and I often walked through this forest at night. A stunning starry sky, snakes hiding in the grass. It seemed to me them that I only had to go outside and I would definitely encounter a goblin or a little mermaid.”

At first, Lena’s parents read to her, but later she read to herself. She read the tales of Hoffmann, the Brothers Grimm, and Andersen, Gerhart Hauptmann‘s novels Atlantis and The Whirlwind of Vocation and, later, Goethe’s The Sufferings of Young Werther.

As a teenager, Lena became interested in heavy music, and wore torn jeans and a bandana. Goths, metal heads and bikers emerged in Kirov. Lena listened to black metal, Lacrimosa, and Korol i Shut, and started hanging out with the “informals” who met at the Kalinka store to play guitar and discuss music. It was there that she met Vlad, her future boyfriend.

“He seemed nice and gallant to me, and paid me a lot of attention. He said he couldn’t live without me, and at the time I took those words seriously. Together we listened to music and watched music videos, and he copied magazine pages for me. At the time I believed that I was difficult to fall in love with, and his attentions won me over,” the writer says.

Over time, Vlad’s attitude towards Lena changed. According to her, the young man didn’t like her friends, calling them whores and asking her to stop hanging out with them. Vlad was jealous of Lena and tried to get her to develop complexes, calling her fat, and if she hung out with other guys, he said that she was a whore. It was then that Vlad hit her for the first time.

“When something bad happened to him, he projected his emotions onto me. For example, I wouldn’t ask how his day had been, or I’d talk to another guy, and he would light up, thinking I didn’t love him or was cheating on him. It was the whole circle of abuse: the outburst, the beating, the promise to improve, and the reconciliation, and after a while everything would repeat again. I understood I was in a bad relationship, but I couldn’t explain why. I thought that if I broke up with him, no one would want me. It was painful without him, but it was worse with him. I hid the bruises and deceived my loved ones,” Lena recalls.

Hanging out with peers helped Lena to get out of the relationship. A club was started at her school in which the kids involved organized celebrations and came up with contests. Hanging out with other teenagers, Lena realized that there was a life without humiliation and aggression, that there was friendship, support, and mutual assistance. Vlad noticed that she was moving away, and there were more quarrels and violence. When it had reached a critical point, they broke up.

“I am convinced that my desire to write texts about LGBT people is connected with the abusive relationships in my youth. I understand that victims of violence and LGBT people living in a homophobic environment are oppressed. They are in a terrible situation, they can’t do anything: they can’t help themselves and no one can help them. When I think about it, I remember my personal experience. And I want to support them emotionally, to say that they are not alone, here is my hand of support. I believe that literature can change the world,” the writer explains.

After leaving abusive relationships and going to high school, Lena met her future husband Ilya. They were also connected by music — Ilya played the guitar. When Lena turned eighteen, the couple decided to get married. The wedding was scheduled for December 2006. But a month before that, a tragedy occurred in the young woman’s family: her dad died in a fire at the sawmill.

“That night, during the fire, Dad was at the sawmill, and we did not completely believe that he had been there. A body was found in the morning. I couldn’t believe for a long time that my father was dead. He often went on business trips, so I thought that he had just gone away this time as well. We buried Dad in a closed coffin,” Lena recalls.

She says that she still could not acknowledge his death. When her father-in-law died, she cried for several days. This was her way of mourning her father.

Part 2. Katya Silvanova’s story: Childhood in Kharkiv and acceptance of her bisexuality

Katya is four years younger than Lena. She spent her childhood in Ukraine, in her hometown of Kharkiv. Currently, the Kharkiv region is being shelled by the Russian military. The lights are constantly turned off in the city for several hours at a time, and the metro comes to a standstill.

Remembering her Kharkiv childhood in the late 90s and early 2000s, Katya says that she was outside in the courtyard a lot. She hung out a lot with the neighborhood kids and constantly rescued animals.

“There was a cat Frosya on our street who suddenly began giving birth. My friend and I stole milk from the house, delivered the kittens, and got them on their feet. Then we picked up a dog that someone had thrown out of the car. We raised money and took it to the vet. And I often went to visit my grandmother in Kryvyi Rih, where I played with the chickens and goats.”

Katya was closest to her mother.

“She read a lot and watched auteur cinema. I always wanted to be with her and her friends. My relationship with my father didn’t work out — he drank and cheated on my mother,” says Katya.

Katya also became interested in reading thanks to her mother — she bought the girl Jules Verne’s In Search of the Castaways. It was followed by Tom Sawyer and, later, Harry Potter, Tanya Grotter, Night Watch, and fantasy novels. It was then that the future writer began inventing worlds, generating ideas from what she viewed and read, and developing characters.

Some readers have criticized LVPG for being written by two heterosexual women. It’s not like that: Katya is bisexual. She thought about her sexuality for the first time in the tenth grade.

“A new girl transferred to our school, and we became friends because we were interested in anime and read manga and fan fiction. I can’t say for sure why yaoi and yuri manga didn’t cause me any surprise. At the age of fifteen, I just accepted as a fact that this exists, that these people exist, and they are no different from us. And then my friend kissed me. That’s how I realized I was bisexual.”

It was not easy for Katya to accept her orientation.

“When people in my group of friends found out that I liked girls, they looked at me strange. When I tried to talk to my parents about LGBT people — not specifically about myself, but in general — their reaction was abrupt and negative.”

The reaction of those around her triggered internal homophobia: Katya began to think something was wrong with her.

Literary representations of her experience helped Katya to cope.

“There are now a lot of LGBT books, films and TV series. But back then I found representations in the yaoi and yuri fan fiction based on Naruto, the comedy manga series Gravitation, and the old anime series of Ai no Kusabi.”

Writing LVPG helped Katya reconcile her parents with her sexuality.

“I told my mom that I like women this year. It took me a long time to work up to it. She was influenced by LVPG — when she was reading the novel, she asked me to explain everything, and I worked on destroying her stereotypes for several years. But in the end, when I told her about myself, she wasn’t surprised. She boldly accepted everything.”

“I now relate to the LGBT community positively and even sympathetically. But it wasn’t always like that. My attitude and acceptance of this topic was completely shaped by Katya. When she was writing the book and I was reading it, we talked a lot, arguing and discussing things. It wasn’t easy to read at first: I was constantly tripped up by the idea that we were talking about two guys. But her talent won me over, and I read the second part of the book excitedly,” says Katya’s mother.

Katya’s maternal grandmother also read LVPG and easily accepted the book’s homoerotic relationships.

“So the lads love each other? Then let them love each other. What’s the big deal? It’s basically a wonderful book,” she argues.

When Katya turned twenty-two, the Euromaidan happened. Due to a fall in the value of the dollar, the trading business owned her by mother was threatened, and the family did not have enough money to buy new pants to replace torn ones. At the time, the future writer had been dating a guy from Nizhny Novgorod and decided to go and stay with him. She recalls the move as fraught with anxiety.

“People were condescending when they found out that I was from Ukraine. But it wasn’t sympathy — they considered me a refugee. It was not an equal relationship, in fact: they put themselves above me, saying that I was poor and unhappy, that I had come to seek shelter in Russia, because allegedly Ukraine was bombing us. Of course, not everyone was like that, but I often encountered a dismissively sympathetic attitude.”

Part 3. Ficbook: Meeting and Working on “Summer in a Young Pioneer’s Tie”

The young women met in 2016 thanks to Ficbook — a website where non-professional authors post their fan fiction, that is, new works based on famous works or characters that are not in any way approved by the authors of the originals. Both Katya and Lena found their way to Ficbook by reading LGBT literature: Katya was looking for representations of same-sex relationships, while Lena wanted to learn more about the lives of LGBT people.

“I was then working at a company where I made friends with a gay guy who was HIV positive. I was shocked and worried and wanted to find out how to help him. I was looking for information, for diaries of people with HIV, and eventually came across Ficbook,” says Lena.

Over time, the young women found the website’s “Originals” section, where authors publish works based not on existing works, but involving completely fictional worlds. Katya and Lena began posting their texts, and having stumbled upon each other’s work, they met on Skype call, during which the authors discussed their works.