Russian businessman, owner of the Concord Group of companies, “Putin’s chef” and confidant of the president, founder of a media empire and the Wagner Group, and one of the most famous people in Russia, Yevgeny Prigozhin now faces criminal charges of organizing an armed rebellion.

Prigozhin was born in Leningrad on 1 June 1961. We know that his mother, Violetta, worked at a hospital, his father died early, and his stepfather Samuel Zharkoy raised the future “Kremlin chef.” Zharkoy also encouraged Prigozhin to ski: his stepson graduated from Athletics Boarding School No. 62, where the swimmer Vladimir Salnikov and the gymnast Alexander Dityatin were his classmates. Prigozhin then enrolled at the Leningrad Chemical and Pharmaceutical Institute, but, according to his own account, he did not finish his degree there.

In 1979, the entrepreneur was given a suspended sentence on robbery charges. According to media reports, in 1981 he was sentenced by the Zhdanov District Court to twelve years in prison for a number of crimes at once, but in 1988 he was pardoned, and in 1990 he was released from prison early.

Beginnings

As Prigozhin himself recounted in an interview, his first business, founded in 1990, was selling hot dogs at the Apraksin Dvor market, the first such outlet in the city. “The mustard was mixed in my apartment, in the kitchen. My mother also tallied the proceeds there. I earned $1,000 a month, and that amounted to piles of rubles,” the businessman said.

In the 1990s, Prigozhin managed Kontrast, a chain of private grocery stores. He launched his future restaurant business in 1995 by opening Wine Club, a bar and shop on Vasilyevsky Island. In late 1996, after meeting the Briton Tony Gere, Prigozhin opened the Old Customs House, which is considered one of the first elite restaurants in Petersburg. According to some reports, his partner in this business venture was Mikhail Mirilashvili, a well-known Petersburg entrepreneur who years later cofounded the VKontakte social media network.

Prigozhin later opened three more establishments: Seven Forty, Stroganov Yard, and Russian Kitsch. In 1998, he opened the restaurant New Island on the used passenger ship Moscow-177, purchased for fifty thousand dollars, which became a popular spot in Petersburg. When Prime Minister Sergei Stepashin and IMF managing director Michel Camdessus visited the city in June 1999, New Island was the only decent place to wine and dine the high-ranking guests.

In 2001, Vladimir Putin dined there with Jacques Chirac, and a year later with George Bush. In 2003, according to media reports, the Russian president celebrated his birthday there. Since the businessman personally served dishes to the president, he was dubbed “Putin’s chef” and “the Kremlin’s chef.”

By that time, Prigozhin had already moved into the catering business, founding Concord Catering in 1995. In 2002, he launched the Damn!Donalds chain of fast food restaurants: the businessman came up with the name himself. The chain was shuttered ten years later, however.

As the businessman recounted in an interview about the success of his catering business, by 2005 he owned “the largest catering company in Russia for ten years running.” “We did all the G8s and the summits,” Prigozhin recalled. From information available in open sources, it follows that the businessman actually did organize a number of banquets for high-ranking guests, including meals at the Russian Federal House of Government.

Buoyed by this success, Prigozhin decided to enter the school meals market. “I decided to try my hand at it and chose a couple of schools on Vasilyevsky Island — No. 10 and No. 18. Of course, it wasn’t a business. I began feeding the schoolchildren airtight-packaged box meals. I set up modern compact kitchens right in the schools — everything fit in a six-square-meter space. At the same time, I carefully researched the topic.”

In the 2000s, Prigozhin went into the construction business. In particular, he built Northern Versailles, a gated mansion community, in Petersburg’s Lakhta district. In 2016, a company belonging to the businessman built the Lahta Plaza [apartment and hotel] complex next to St. Petersburg Tricentennial Park.

In 2016, it transpired that a Prigozhin-affiliated company bought the premises of the Shop of Merchants Yeliseyev, which he had occupied on lease since 2010, after making expensive renovations. By 2015, Prigozhin’s companies had become the largest supplier of food to the Defense Ministry.

In 2018, Vladimir Putin said in an interview with western media, “He is not my friend. I know such a person, but he is not on my list of friends.”

Media Empire

In 2013, it was reported that the Internet Research Agency, which was informally dubbed the “troll factory,” was located on Savushkin Street in Petersburg. Hundreds of people worked on the media holding’s websites. Prigozhin’s connection with the growing media empire was denied by Concord’s press service.

2019 saw the emergence of the Patriot Media Group, which included the Federal News Agency (FAN), Economy Today, Politics Today, and Nation News. Yevgeny Prigozhin headed its board of trustees, but the businessman’s financial involvement in the project was denied.

Western sanctions against Prigozhin were imposed for the first time over the involvement of his media outlets in the information campaign [sic] for the US presidential election.

Wagner

The Wagner Group, a private military company, was founded in 2014. Subsequently, Wagner soldiers were involved in fighting in eastern Ukraine and, later, in Syria. In 2017, the company was placed on the US sanctions list. But [Prigozhin] admitted his involvement in founding Wagner only in 2022. Western countries have claimed that Wagner mercenaries have also operated in Libya, the Central African Republic, Sudan, Mozambique, and Mali.

SMO

Since 24 February 2022 and the beginning of the SMO, Prigozhin gained worldwide fame in connection with the Wagner Group’s actions in Ukraine. Wagner’s troops have been heavily involved in the fighting. Mercenaries recruited among convicts have been actively joining the ranks of Wagner PMC. In March, the businessman claimed that over 5,000 ex-convicts had returned to Russia after participating in combat.

The conflict between the Defense Ministry and Prigozhin rapidly deteriorated in 2022, although friction between the two parties had essentially begun several years earlier.

A year later, in February 2023, Prigozhin publicly voiced dissatisfaction with the lack of ammunition during the battles for Bakhmut (Artemovsk). A campaign entitled #GiveWagnerShells gained momentum on the internet.

On May 10, the businessman, amid rumors of a “shell famine,” publicly announced his willingness to transfer Wagner’s positions in Bakhmut to Chechnya’s Akhmat Regiment at the suggestion of Chechen ruler Ramzan Kadyrov. On May 20, the businessman said that Wagner had taken Bakhmut, and once again made highly critical remarks about the Defense Ministry. Five days later, Prigozhin announced that he was withdrawing his units from the city.

In June 2023, the businessman asked Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu to release the Concord Group from its catering contract in the SMO zone after more than sixteen years of successful cooperation with the Russian military’s kitchens.

Moreover, Prigozhin said that an order that members of volunteer detachments must sign contracts with the Defense Ministry did not apply to the Wagner Group.

Then came June 23. Wagner’s founder made new public statements, triggering criminal charges against him. If convicted, Prigozhin faces up to twenty years in prison.

Source: Irina Kurbat, “Who is Yevgeny Prigozhin?” Fontanka.ru, 24 June 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader

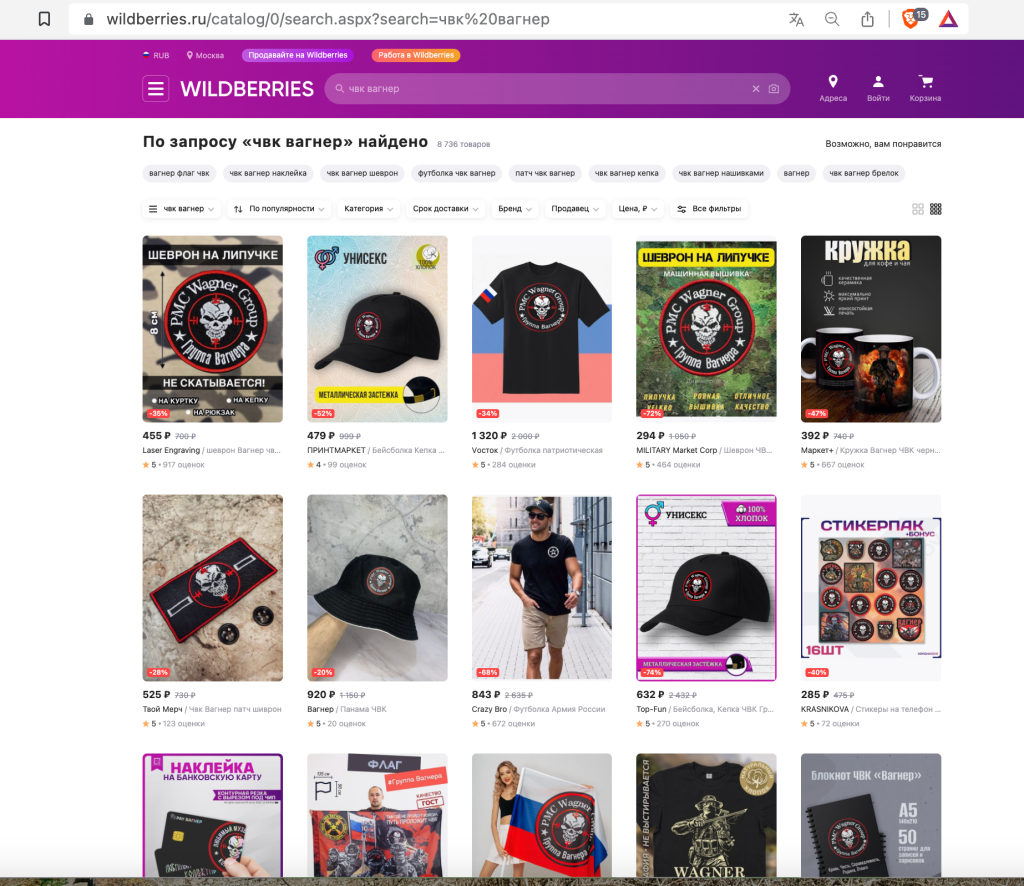

Goods bearing the emblems of the Wagner Group (including chevrons, flags, t-shirts, baseball caps, and sewn-on patches) have been brought back to the “counters” at Wildberries, as our correspondent verified on the evening of June 24.

In the first half of the day, a source at Wildberries told RIA Novosti that the online retailer had bearing removing goods bearing the [private military] company’s emblems and was going to remove them altogether. Later, such goods were hidden by Ozon, where they are still unavailable.

Source: “Wildberries brings back Wagner-branded goods,” Fontanka.ru, 24 June 2024. Translated by the Russian Reader

Zenit FC midfielder Wendel has decided not to return to Petersburg due to the situation with the Wagner PMC, reports Sport Express, citing the player’s agent Cesare Barbieri.

“This is definitely a very delicate situation. Wendel will stay in Brazil until the situation improves. The club has already been notified of this. Zenit has reacted understandingly to the situation,” the agent said.

In the 2022–2023 season, 25-year-old Wendel has played twenty-five matches for Zenit in the Russian Premier League, scoring eight goals.

Source: “Zenit football player Wendel afraid to return to Russia,” Fontanka.ru, 24 June 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader

Petersburg Governor Alexander Beglov (in mask, on right) visited the city’s Maternity Hospital No. 9 on May 3. Photo courtesy of

Petersburg Governor Alexander Beglov (in mask, on right) visited the city’s Maternity Hospital No. 9 on May 3. Photo courtesy of  Photo by Mikhail Ognev. Courtesy of Fontanka

Photo by Mikhail Ognev. Courtesy of Fontanka

Metropolitan Varsofonius and his crew. Photo by Andrei Petrov. Courtesy of the St. Petersburg Archdiocese of the Russian Orthodox Church and Fontanka.ru

Metropolitan Varsofonius and his crew. Photo by Andrei Petrov. Courtesy of the St. Petersburg Archdiocese of the Russian Orthodox Church and Fontanka.ru

The Lakhta Center skyscraper construction site in November 2018. Photo by the Russian Reader

The Lakhta Center skyscraper construction site in November 2018. Photo by the Russian Reader

Eve’s Ribs Festival organizer Leda Garina and a police officer. This photo was posted yesterday on

Eve’s Ribs Festival organizer Leda Garina and a police officer. This photo was posted yesterday on  Petersburg police muster at five in the morning on May 29 in the parking lot of the Soviet-era Sport and Concert Complex (SKK) in the southern part of the city before heading off to raid the homes and workplaces of Central Asian migrant workers. Photo courtesy of

Petersburg police muster at five in the morning on May 29 in the parking lot of the Soviet-era Sport and Concert Complex (SKK) in the southern part of the city before heading off to raid the homes and workplaces of Central Asian migrant workers. Photo courtesy of