(A Quiet) Civil War • Dictionary of War, Novi Sad edition, January 25–26, 2008

My concept is “civil war”— or rather, “a quiet (civil war).” Another variant might be: cold civil war. I will talk about how the (global) economy of war—hot war, cold war, civil war—is experienced by victims and bystanders in a place seemingly far from actual frontlines. In reality, the frontlines are everywhere—running down the middle of every street, crisscrossing hearts and minds. This permanent war is connected to the project that posits the presence of civil society in one part of the world, while also asserting the necessity of building civil society in other parts of the world where allegedly uncivil social, political, and economic arrangements have been or have to be abolished. The real effect of this high-minded engineering is the destruction of people, classes, and lifestyles whose continued survival in the new order is understood (but hardly ever stated) to be either problematic or unnecessary. The agents of this destruction are varied—from random street crime, assassinations, inflation, alcoholism, factory and institute closures, to pension and healthcare reform, the entertainment and news industry, and urban renovation. The place I will talk about is Russia and Saint Petersburg, where I have lived for much of the past fourteen years. My concept is intended as a memorial to a few victims and local eyewitnesses of this war—people I either know personally or came to know about through the stories of friends or other encounters. I will also sketch the tentative connections between that civil war and the troubles in this part of the world; and, very briefly, show how the victors in this war claim their spoils.

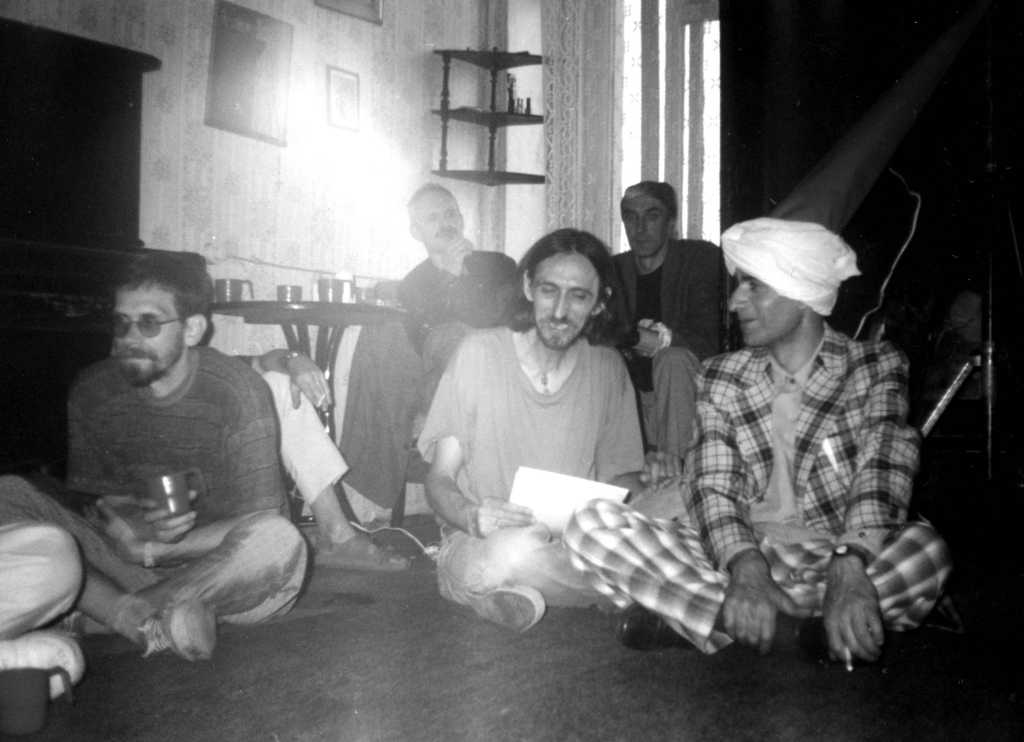

This term—(a quiet) civil war—was suggested to me by the Petersburg poet Alexander Skidan during a conversation we had last spring. I had been telling Alexander about the recent murder of my friend Alexei Viktorov. Alexei is fated to remain a mere footnote in Russian art history. I mean this literally: in a new book, Alexei is correctly identified as the schoolmate of the Diaghilev of Petersburg perestroika art, Timur Novikov, and the painter Oleg Kotelnikov. I met Alexei in 1996, when Oleg let me live in his overly hospitable studio in the famous artists squat at Pushkinskaya-10. Alexei showed up a few weeks later. He had spent the summer in the woods, living off mushrooms and whatever edibles he could find. In his youth, he had acquired the nickname Труп (Corpse). With his gaunt features and skinny frame, he certainly looked the part. As I would soon discover, he was one of the gentlest men on earth. He was also a terrific blues guitarist. And he was the first Hare Krishna in Leningrad and, perhaps, the entire Soviet Union—which was quite a feat, considering that his conversion took place in the dark ages of the seventies.

Last winter, friends chipped in on a plane ticket, and Alexei was able to fulfill a lifelong dream and travel to India. When he and his companions arrived at the Krishna temple, Alexei was greeted by the community as a conquering hero. Since Alexei’s life had been quite miserable of late back home, his friends insisted that he stay behind in India. Instead, he decided to return to Petersburg. A few days after his arrival home he was walking from the subway in the northern Lakes district of the city to the house of a friend. Along the way he was attacked—the police say by a gang of teenagers. The teenagers beat Alexei within an inch of his life and pushed him into a ravine. The police investigator guessed that Alexei had lain unconscious for some time. When he came to, he had apparently struggled to raise his battered body up and clamber out of the ravine; in his struggle, he had for some reason started tearing off his clothes, perhaps because his rib cage and chest were so badly crushed that he was suffocating. His body was discovered a couple days later. The police held it for another few days while they completed their investigation, which led to no arrests. Alexei’s funeral was held a few days afterwards at the Smolensk Cemetery on Vasilievsky Island. He was buried a few hundred meters from the grave of his schoolmate Timur Novikov, who died in 2002.

It was this story that prompted Alexander Skidan’s remark to me: “A quiet civil war has been going on here.” What did Alexander have in mind? What could the random albeit violent murder of a single human being have in common with the explicitly political and massively violent struggles that have taken place here in the former Yugoslavia and such parts of the former Soviet Union as Abkhazia, Southern Ossetia, Tajikistan, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Chechnya? How could Alexei—who, as the Russian saying has it, lived “quieter than the water, lower than the grass”—be viewed as an enemy combatant in such a war? Can we really compare his unknown assailants to representatives of the opposite warring party? Given what they did to him, it is clear that they viewed Alexei as their enemy—an enemy subject to sudden, violent execution when encountered in the proper (hidden, invisible) setting.

I anticipate serious objections to my line of argumentation. One such objection I have already heard in the person of my friend Igor. Igor, whose father is Ossetian, and whose mother is Ukrainian, grew up in Dushanbe, which was then the capital of the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic. I have never been to Dushanbe, but I have heard Igor describe it so many times in such glowing terms that I have come to think of it as heaven on earth. While I am sure that much of the paradisiacal tone in Igor’s recollections has to do with temporal and physical distance, it really does seem that the Dushanbe of the sixties and seventies was a kind of cosmopolitan oasis—a place where all sorts of forced or voluntary exiles from all imaginable Soviet ethnic communities and other cities ended up living in something like harmony.

This harmony bore the name “Soviet Union,” and Igor himself has often seemed to me the ideal homo soveticus (in the positive, internationalist sense of that term), a person to whom the refrain of the popular song—“My address isn’t a street or a building, my address is the Soviet Union”—fits perfectly. Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Igor was the country’s leading expert on the seismic stability of electrical substations. From the onset of the Tajik civil war, in the early nineties, Igor was unable to return to Dushanbe. This had to do with the fact that in his internal Soviet passport, his place of birth was identified as Khorog, the capital of the Pamir region, which is where some of the “anti-government” forces had their power base. If Igor had returned to Dushanbe, he could easily have been stopped by soldiers during a documents check and executed on the spot. This is what happened to a number of his friends and schoolmates.

After the war was over, Igor’s father was able to reclaim the family home near Vladikavkaz, in Northern Ossetia, which had been confiscated by the authorities when Igor’s grandfather had been executed as an enemy of the people in the thirties. Northern Ossetia was a relative oasis during the nineties, despite the fact that Chechnya and Ingushetia were just over the mountains and neighboring Southern Ossetia had broken away from Georgia. This relative calm came to an abrupt end in September 2004, when terrorists besieged the school in neighboring Beslan. During the siege, members of Igor’s extended family were killed.

This is how Igor puts it: “Civil war is when the bus you’re on is stopped by soldiers and some of the passengers are taken off to be shot. And you sit there in the bus listening to the sound of gunfire and waiting for it to be over so that you can continue on your way. That’s civil war. What you’re talking about is not civil war.” Igor is certainly right.

He is also wrong in another sense. The quiet civil war I am describing here—among whose victims, I claim, was our friend Alexei—draws its energy and some of its methods from the real civil wars that have been fought in the hinterlands that are literally unthinkable to folks in such seemingly safe, prosperous places as Petersburg and Moscow. An immediate consequence of the siege in Beslan was that President Putin abolished gubernatorial elections in the Russian Federation’s eighty-four regions and federal cities. This, it was argued, would strengthen Moscow’s control—its so-called power vertical—over local officials whose incompetence and corruption had led, supposedly, to guerrillas infiltrating Beslan and capturing the school with such ease. Meanwhile, the civil wars and socioeconomic collapse in places like Tajikistan have led to a flood of refugees and migrant workers into Central Russia and its two capitals. The booming building trade in Moscow and Petersburg to a great degree now depends on the abundant, cheap supply of workers from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Moldova, and other former Soviet republics.

These workers are literally visible everywhere nowadays: with the oil economy fueling a tidal wave of consumerism whose major players have now turned to real estate as an outlet for investing their wealth, the capitals have become gigantic construction sites. And yet the conditions of their work and their lives are just as literally invisible. For example, Tajik workers and other darker-skinned Central Asians and Caucasians are subjected to frequent, unnecessary documents checks in public places such as subway stations. This is something that every Petersburger and Muscovite has seen ten thousand times, but it is also something they pretend not to see, judging by the lack of public reaction to the practice. Even less reaction is generated by neo-Nazi attacks on such workers, other foreigners, members of Russia’s ethnic minorities, and anti-fascist activists, which have become more and more common in the past several years.

I want to paint one more, brief verbal portrait of another victim in this quiet civil war. This portrait is connected with the violence inflicted on this city and other parts of Serbia during the NATO bombing campaign of 1999. The official and popular reaction in Russia to this violence was quite harsh. There were massive demonstrations outside the US embassy in Moscow; unknown assailants even fired a grenade into an empty office at the embassy. What surprised me were the more spontaneous reactions to the bombings. One day, a young American artist and I were standing in the courtyard of the squat at Pushkinskaya-10 chatting with a local artist. Two acquaintances of ours—members of a well-regarded alternative theater troupe—entered the courtyard. When they saw us, they shouted, “Don’t talk to those Americans! They’re bombing our Serbian brothers!” Since they said all this with a smile, it was hard to know to what extent we were supposed to take their warning as a “joke.”

It occurred to me then that a fundamental shift was occurring in the consciousness of Russians who had been, both in practical and philosophical terms, “westernizers” and “liberals” not long before. That this shift was also extending into the “masses” was confirmed for me a few days later. Late one night, I suddenly heard a drunken-sounding young man yelling up to an apartment across the street: “Masha! Goddammit, come downstairs and let me in!” Since repeated requests had no apparent effect on the silent, invisible Masha, the young man became more explicit in declaring his unhappiness with Masha’s thwarting of his affections. “Masha, you fucking bitch, come down and let me in! You’re breaking my fucking heart!” The turn the man’s soliloquy took next, however, signaled to me that we all were living in a new world. “Masha, go fuck yourself! NATO, go fuck yourselves!” (Маша, пошла ты в жопу! Блок НАТО, пошли вы в жопу!) This effusive condemnation of Masha and NATO continued for some time, after which the thwarted lover fell silent or fell over drunk.

If I had known that I would be invited to speak at this conference nine years later, I would have recorded the whole performance. Instead of speaking to you now, I would have played back the recording in full. Not in order to make fun of the young man whose heart had been broken in two by the combined forces of Masha and NATO, but so that you could hear what the quiet civil war I am trying to talk about sounds like. This is what I meant when I said, at the beginning of my remarks, that the frontlines in this new kind of war cross through hearts and minds and run down the middle of streets. This is not what happens when civil society breaks down; it is what happens when “civil society” is a code word (pronounced and enacted in tandem with other code words such as “democracy” and “liberal economy”) used to camouflage the incursion into the city of invading forces. The new regime they have come to establish can in reality do quite happily without “civil society,” democracy, and liberalism. But these words and the real actions taken and deals made behind their smokescreen are quite effective in destroying the historic and imaginary forms of solidarity that might have given folks like our unhappy young lover the means to defend themselves somehow. Instead, we end up with the muddle in our heads that lets us imagine that Masha and NATO are allied against us. Or that NATO is bringing democracy and security to Afghanistan. Or that, instead, to thwart NATO’s expansion to the east we have to round up Georgian restaurant workers and deport them back to Georgia—which, paradoxically, used to be nearly every Russian’s favorite place on earth.

As Alexander Skidan himself told me, the NATO bombing campaign of 1999 really had destroyed the illusions that he and most everyone else he knew had both about the west and about the meaning of the radical transformation of Russian society that was carried out under the banner of a rapprochement with the west and a leap forward into liberal democracy and neoliberal capitalism. What Alexander and his friends saw as the west’s treachery in the Kosovo crisis had thrown a new retrospective light on a period they had until then been experiencing as a golden age for artists and ambitious young people like themselves—an age of unprecedented opportunity for self-expression at home and dizzying trips abroad. Why hadn’t the massive immiseration and unemployment of the post-Soviet population during the early nineties produced this same enlightenment? Or the violent disbanding of the Russian parliament, in 1993? Or the first war in Chechnya? Or the fact that, in Alexander’s case, his own father, a professor at the city’s shipbuilding institute, had gone in a matter of a year or two from being a respected member of his society to being an outmoded nobody who had to struggle to survive? Somehow, Alexander and his kind had noticed all this, of course, and not seen it. Or seen it and decided that these were the sort of temporary measures and necessary obstacles on the road to a better future. As he sees it now, the whole point of the Russian nineties was to decommission and eliminate whole sections of the population—teachers, doctors, factory workers, the poor, the aging, the less ambitious, and the more gullible. And this civil war, which continues to this day, paved the way to the quite logically illiberal current regime.

Which of course is wholly staffed by the victors in the quiet civil war of the nineties—not by the victims, whose victimhood is converted into ever-greater quantities of political, symbolic, and real capital by those same victors. Thus, the current favorite to win the Russian presidential elections in March announced the other day that his goal was to create a strong civil society where the freedoms and rights of all citizens would be cherished and protected.

This is one way to cash in your chips at the end of a successful quiet civil war. But our globalizing economy is such that you can even profit from someone else’s civil wars. My favorite new example of such capitalization is the American alternative band Beirut, the brainchild of 22-year-old Zach Condon, a native of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Overly sensitive types might wonder how you grow up in peaceful Santa Fe and end up calling your band Beirut—but as we Americans love to say, It’s a free country.[1] (In its article on the band’s “Balkan-inspired” debut album, Gulag Orkestar, Wikipedia helpfully explains that the “Gulag was a system of Russian [corrective labor camps] in Siberia.”)

It is too much to expect that alternative radio stations would play, instead of Beirut’s fake Balkan wedding music, the 1999 lament of Masha’s spurned lover. Besides, I didn’t have the good sense to record it and release it as an album.

[1] “One of the reasons I named the band after that city was the fact that it’s seen a lot of conflict. It’s not a political position. I worried about that from the beginning. But it was such a catchy name. I mean, if things go down that are truly horrible, I’ll change it. But not now. It’s still a good analogy for my music. I haven’t been to Beirut, but I imagine it as this chic urban city surrounded by the ancient Muslim world. The place where things collide.” Rachel Syme, “Beirut: The Band,” New York, 6 August 2006.

Dmitry Poletayev, Vyacheslav Kryukov, Ruslan Kostylenkov, and Pyotr Karamzin, defendants in the New Greatness trial, during a court hearing. Photo by Pyotr Kassin. Courtesy of Kommersant and Republic

Dmitry Poletayev, Vyacheslav Kryukov, Ruslan Kostylenkov, and Pyotr Karamzin, defendants in the New Greatness trial, during a court hearing. Photo by Pyotr Kassin. Courtesy of Kommersant and Republic Anastasia Shevchenko

Anastasia Shevchenko The Zenit Arena in Petersburg is the most expensive football stadium in history. And one of the ugliest. Photo by the Russian Reader

The Zenit Arena in Petersburg is the most expensive football stadium in history. And one of the ugliest. Photo by the Russian Reader