Photo: Yulia Morozova/Reuters via the New York Times

It seems that one of the consequences of this tragedy [i.e., the terrorist attack on the concert hall in suburban Moscow] has been the legalization, or legitimization, of torture. Torture existed before, but it was concealed and formally condemned. Now torture is openly praised and flaunted, and state institutions, including courts, do not react in any way. Another step towards fascization.

Source: Sergey Abashin (Facebook), 25 March 2024. Translated by the Russian Reader

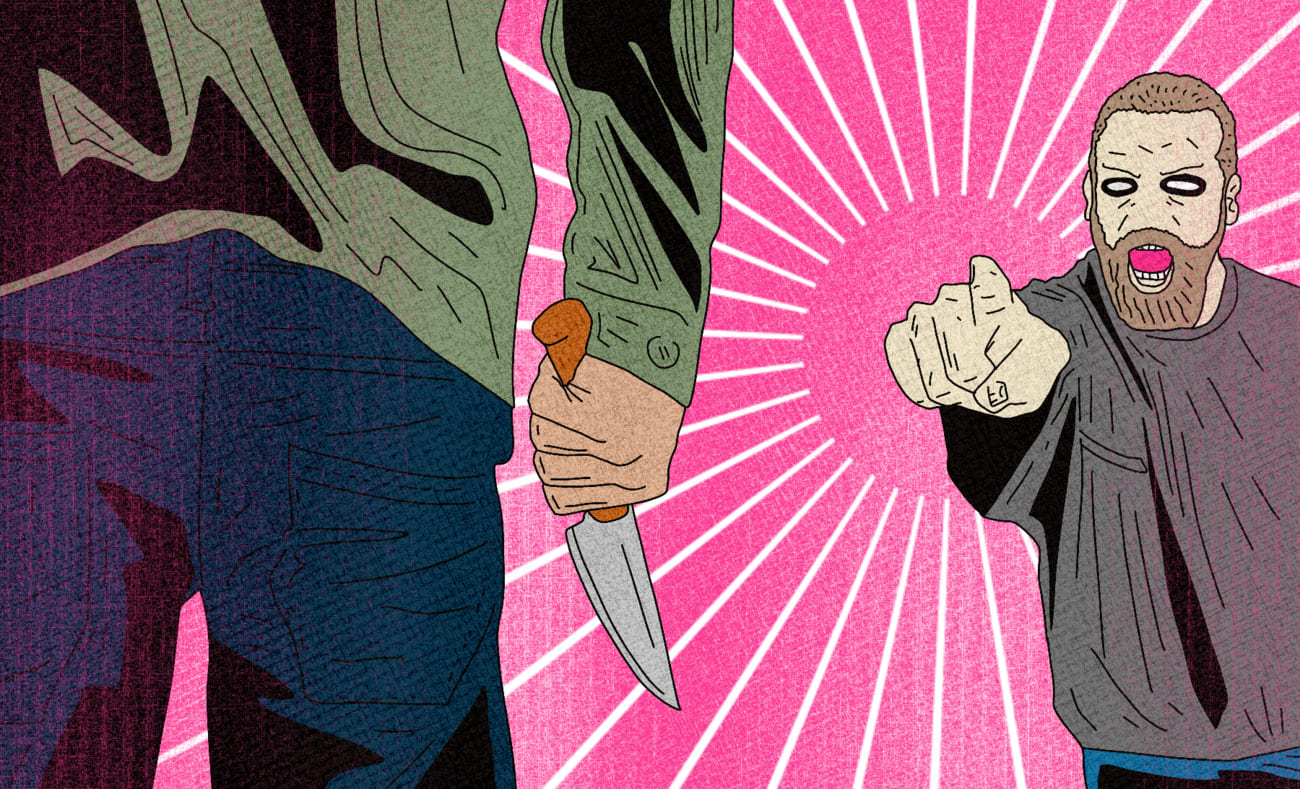

Warning: this newsletter contains numerous descriptions of violence and torture.

People are tortured every day in Russia. For a long time we have been hearing about torture in penal colonies and police departments from victims and human rights activists. Mops and electric shockers have been mentioned in reports in the independent media and in the accounts of people who were subjected to violence, but the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) and the police themselves have usually denied the accusations. Even in today’s Russia, however, the courts have periodically tried to imprison law enforcers who have tortured people, such as those implicated in the Karelian penal colony case, the Yaroslavl case, and the Saratov prison hospital case.

The terrorist attack in suburban Moscow has changed everything.

On 22 March, gunmen killed at least 137 people at the Crocus City Hall concert venue outside Moscow. They set fire to the building and left before the police arrived. Law enforcers have already detained suspects, and the Z bloggers have been salivating over the photos and videos of their abuse at the hands of the authorities. Never before have we had such flagrant acknowledgement of torture.

“The law enforcers have often covered their tracks by sweeping stories of torture under the rug, and we were told that there was no torture, that the reports were nonsense,” Sergei Babinets, head of the Crew Against Torture, said in an interview with Mediazona. “But since yesterday it seems as if there is a path to making torture a little more public.”

Dalerdzhon Mirzoyev (whom propagandist Margarita Simonyan dubbed the “ringleader” of the terrorists) was brought to his arraignment hearing with bruises on his face and remnants of a bag around his neck. He had no bruises at the time of his arrest, and the bag could have been used by law enforcers to strangle Mirzoyev. When the judge announced the pretrial restraint measures (Mirzoyev was remanded in custody to a pretrial detention center) Mirzoyev could not stand up. Instead, he leaned against the wall of the “fish tank” in the courtroom.

Saidakrami Murodali Rachabalizoda was brought to the hearing with his head bandaged. A law enforcer had cut off his ear when he was detained and tried to make him eat it. Neo-Nazi Yevgeny “TopaZ” Rasskazov of the nationalist subversive group Rusich announced an auction for the knife that was allegedly used to cut off Rachabalizoda’s ear.

The third detainee, Shamsidin Fariduni, was also apparently tortured. Telegram channels associated with law enforcement circulated a photo of Fariduni lying on the ground with his pants pulled down and law enforcement officers standing over him. There are wires from a field telephone attached to his groin. Such wires are used to electrocute detainees. (They have been used, for example, on detained Ukrainians in the occupied territories.) And someone is also stepping on Fariduni with a foot shod in an army tactical boot. Fariduni arrived in court with a swollen and beaten face.

Finally, the fourth detainee, Muhammadsobir Faizov, came to the court from the intensive care unit in a wheelchair. He could barely speak, and was hooked up to a catheter and a urinal. One of his eyes was injured. For the duration of the hearing, his doctors—two women in ambulance corps uniforms who had arrived with Faizov—were asked to leave the courtroom.

Why is this happening? Sergei Babinets argues that law enforcers could have been affected by the absence of major terrorist attacks in recent years.

“Many people were simply not ready for it—not ready emotionally, not ready psychologically, not ready on various fronts. And people may have started to lose their nerve due to this. That’s why there have been calls to reinstate the death penalty, to locate all the guilty parties and execute them, for example,” he said.

Аccording to Babinеts, Russian aggression in Ukraine has also played a role.

“The normalization of violence may have aggravated the situation with torture. We can see that law enforcement officers are really starting to let themselves go more,” he said.

Babinets adds, however, that there is no point to this violence.

“Torture most often leads to the torturer obtaining the information he wanted to obtain initially,” he said. “If they want a person to confess that they had been working, for example, for the Ukrainian army, they can be tortured until they confess. It is impossible to effectively investigate crimes in this way.”

Source: “Torture has gone public,” WTF? newsletter (Mediazona), 25 March 2024. Translated by the Russian Reader

It’s more than two decades since I read the late Stanley Cohen’s ground-breaking States of Denial: Knowing About Atrocities and Suffering (2001). In the introduction, Cohen recalls his own experiences growing up in apartheid South Africa, when he asked himself why his own outrage at the injustice he observed all around was not reflected in the society around him:

Why did others, even those raised in similar families, school and neighbourhoods, who read the same papers, walked the same streets, apparently not “see” what we saw. Could they be living in another perceptual universe — where the horrors of apartheid were invisible and the physical presence of black people often slipped from awareness? Or perhaps they saw exactly what we saw, but just didn’t care or didn’t see anything wrong.

Cohen went on to become a sociologist and a lifelong human rights activist. States of Denial was a valiant attempt to bring his discipline to bear on the subject of why people become become ‘everyday bystanders’ of atrocities who ‘block out, shut off or repress’ troubling or disturbing information to the point when they ‘react as if they do not know what they know.’

Some of these observations related to Israel, where Cohen moved in 1980. A Zionist in his youth, Cohen opposed the military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and became a strong critic of Israeli repression of the Palestinians. In his book, he describes his work with the Israeli human rights group B’Ttselem on the torture of Palestinian detainees and the obstacles it encountered:

Our evidence of the routine use of violent and illegal methods of interrogation was to be confirmed by numerous other sources. But we were immediately thrown into the politics of denial. The official and mainstream response was venomous: outright denial (it doesn’t happen); discrediting (the organization was biased, manipulated or gullible); renaming (yes, something does happen, but it is not torture); and justification (anyway ‘it’ was morally justified). Liberals were uneasy and concerned. Yet there was no outrage.

Cohen returned to the UK in 1996, and died in 2013, but were he alive today, I suspect he would have recognized the ongoing devastation of Gaza as a textbook example of the ‘politics of denial’. According to the latest figures from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the IDF has killed more than 31,988 people, most of whom are women and children, with another 7,000 buried in the rubble, and wounded 74,188. To put these figures in perspective, this February civilian casualties in Ukraine were estimated at 10,582 dead and 19,875 injured since the Russian invasion began on 24 February 2022.

So in just under six months, Israel has killed more civilians in Gaza than Russia has killed in two years. It has destroyed or damaged more than 60 percent of Gaza’s housing stock, 3 churches, 224 mosques, 155 health centres, 126 ambulances. Nearly 2.3 million Palestinians have been displaced, and 1.1 million people are facing ‘catastrophic levels of food insecurity,’ which threatens to become a famine.

All this has been done with the indirect support or direct collusion of the United States government, the European Union, and the British government. Despite the outpouring of rage and horror on the streets of so many cities across the world, liberal democracies that claim to uphold an international order based on human rights and universal moral norms have ‘known and not known’ what has been taking place in front of their eyes.

Many of these governments once railed against ‘dictators killing their own people’, and used atrocities and human rights abuses as a moral lubricant for liberal ‘interventions’ and ‘ humanitarian’ wars to prevent ‘massacres’ and ‘bloodbaths.’ Apart from a few tepid words of condemnation, when the obscenity of what is unfolding became too much to ignore, these same governments have enabled Israel to inflict incredible carnage on a mostly unarmed and defenceless population.

None of is taking place in secret. In February, Amnesty claimed that ‘Fresh evidence of deadly unlawful attacks in the occupied Gaza Strip…demonstrates how Israeli forces continue to flout international humanitarian law, obliterating entire families with total impunity.’ Israeli soldiers routinely post tweets and TikTok videos of themselves gleefully blowing up Palestinian homes, wearing Palestinian lingerie and women’s dresses, humiliating Palestinian prisoners made to strip down to their underwear, and generally exulting in the destruction.

[…]