Tajikistan has condemned what it called an “ethnic hatred” attack in Russia after a 10-year-old boy from a Tajik family was stabbed to death at a school near Moscow, in a rare public rebuke aimed at a key partner for labor migration and security ties. The killing happened on December 16 in the village of Gorki-2 in the Odintsovo district of the Moscow region, according to Russia’s Investigative Committee, which said a minor attacked people at an educational institution, killing one child and injuring a school security guard.

A video of the attack circulated on Russian social media after the incident. According to reporting by Asia-Plus, footage published by the Telegram channel Mash shows the teenage assailant approaching a group of students while holding a knife and asking them about their nationality. The video then shows a school security guard attempting to intervene before the attacker sprays him with pepper spray and stabs him. The assailant subsequently turns the knife on the children, fatally wounding the 10-year-old boy.

A statement released by Tajikistan’s interior ministry said it feared the case could “serve as a pretext for incitement and provocation by certain radical nationalist groups to commit similar crimes.” Tajikistan’s response also drew attention after the foreign ministry said the attack was “motivated by ethnic hatred.” Dushanbe subsequently summoned the Russian ambassador to protest the attack, handing him a missive “demanding that Russia conduct an immediate, objective, and impartial investigation into this tragic incident.”

The condemnation is particularly notable as Tajikistan rarely issues public criticism of Russia, which remains its main destination for migrant labor and a key security partner.

According to Russian media, the attacker, who has admitted their guilt, subscribed to neo-Nazi channels and had sent his classmates a racist manifesto entitled “My Rage,” in which he expressed hostility toward Jews, Muslims, anti-fascists, and liberals, a few days before the incident.

Tajik migrants form one of the largest foreign labor communities in Russia and across Central Asia. Millions of Tajik citizens work abroad each year, most of them in Russia, sending remittances that are a critical source of income for families at home. According to the World Bank, remittances account for roughly half of Tajikistan’s gross domestic product in some years, making labor migration a cornerstone of the country’s economy. Many Tajik migrants work in construction, services, and transport, often in precarious conditions and with limited legal protections. The killing comes as Central Asian migrants in Russia face growing pressure to enlist in the war in Ukraine, with coercion through detention, deportation threats, and promises of legal status having been reported.

The killing has also renewed scrutiny of rising xenophobia in Russia, particularly toward migrants from Central Asia. The Times of Central Asia has previously reported an increase in hate speech, harassment, and violent attacks targeting migrants, especially following major security incidents. Human Rights Watch has warned that Central Asian migrants in Russia face growing discrimination, arbitrary police checks, and racially motivated abuse, trends that have intensified in recent years amid heightened nationalist rhetoric.

Source: Stephen M. Bland, “Tajikistan Condemns Fatal Stabbing of Boy in Russia Citing Ethnic Hatred,” Times of Central Asia, 17 December 2025

It’s curious. I looked through some of the [social media] pages of Russia’s [most prominent] political émigrés—[Ilya] Yashin, [Vladimir] Kara-Murza, [Ekaterina] Schulmann, [Leonid] Volkov, [Elena] Lukyanova, [Dmitry] Bykov, [Marat] Gelman, [Boris] Zimin, [Boris] Akunin—but I couldn’t find a word about the violent death of a Tajik boy in a school near Moscow. They have expressed no sympathy, voiced no criticism of racism and xenophobia. It seemingly should be their direct obligation to speak out on this issue. But for some reason, mum’s the word. I also looked at the Telegram channels of the leading official anthropologists, and there is a mysterious muteness among them too. Surely it is their professional duty not to remain silent on such a matter. They even published a book called Tajiks and themselves speak everywhere of interethnic harmony. But in this case, it’s as if they’ve dummied up.

Source: S.A. (Facebook), 18 December 2025. Translated by the Russian Reader

As FB is reminding, there were times I believed I could protect my non-Slavic looking friends, lovers, relatives, foreign students and migrant workers from the nazis marching in the streets, from the nazis working as policemen, from the general xenophobia and unsensibility by magic tricks of art.

Source: Olga Jitlina (Facebook), 18 December 2025

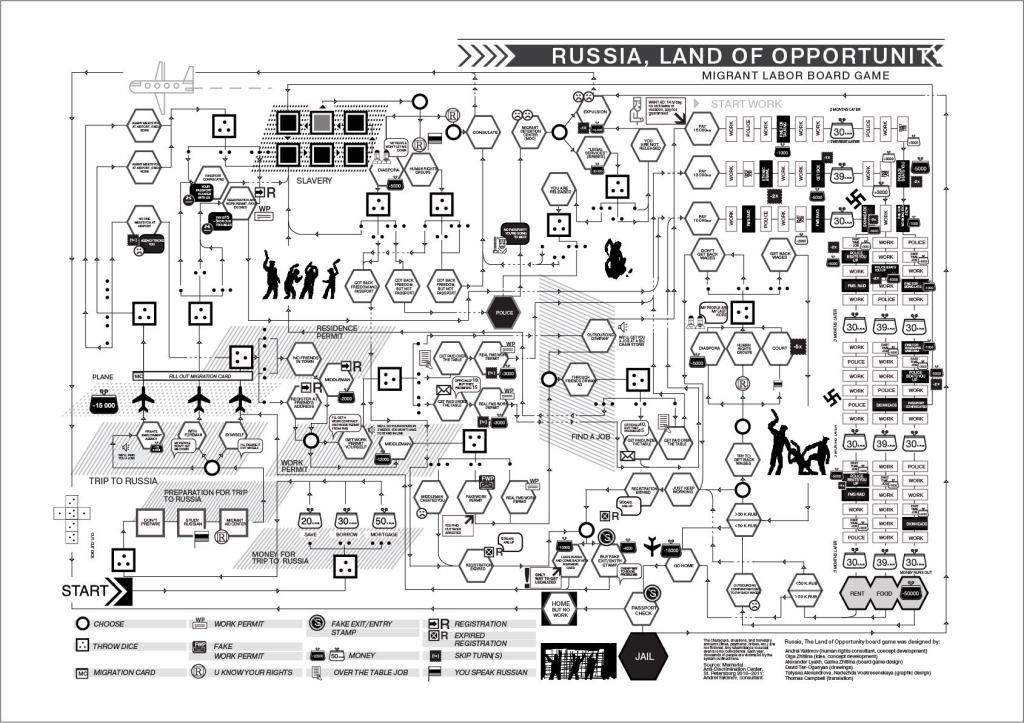

Thomas Campbell just translated our migrant labor board game Russia – The Land of Opportunity!!!

Russia – The Land of Opportunity board game is a means of talking about the possible ways that the destinies of the millions of immigrants who come annually to the Russian Federation from the former Soviet Central Asian republics to earn money play out.

Our goal is to give players the chance to live in the shoes of a foreign worker, to feel all the risks and opportunities, to understand the play between luck and personal responsibility, and thus answer the accusatory questions often addressed to immigrants – for example, “Why do they work illegally? Why do they agree to such conditions?”

On the other hand, only by describing the labyrinth of rules, deceptions, bureaucratic obstacles and traps that constitute immigration in today’s Russia can we get an overall picture of how one can operate within this scheme and what in it needs to be changed. We would like most of all for this game to become a historical document.

Source: Olga Jitlina (Facebook), 17 December 2011

Life for migrant workers is Russia is becoming increasingly difficult after stringent new controls introduced over the past year. These include a registry of “illegal” migrants, restrictions on enrolling migrant children in schools, new police powers to deport people without a court order, and a compulsory app for all new migrants in Moscow and the surrounding region to track their movements.

Working in Russia was already less appealing because of the war in Ukraine and the weakening rouble. Now, with these new restrictions, a growing number of young people from Central Asia are starting to look elsewhere — including to countries in Europe — in search of better opportunities.

Dreaming of Europe in Moscow

Like 89% of young Kyrgyzstanis, 25-year-old Bilal* had always dreamed of working abroad.

Young people in Kyrgyzstan grow up in an environment where leaving the country to find work is common, widespread, economically essential, and socially accepted — and where the domestic economy still cannot offer comparable opportunities.

The average monthly salary in the country is about 42,000 soms (around $480), while in Russia, for example, wages in manufacturing can reach 150,000 rubles (nearly $2,000). Unlike most of his peers, Bilal never planned to work in Russia. “Because many of our people face racism there,” he explains.

Europe was his dream, but without connections getting a job offer from an EU employer seemed nearly impossible. So Bilal turned to “intermediaries” — fellow Kyrgyzstanis who had established ties with European companies that were constantly seeking workers. They advised him to travel to St. Petersburg, where, they said, it would be easier to prepare the paperwork and apply for a visa.

But it was the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many Schengen countries had stopped issuing visas and temporarily shuttered their consulates. Bilal didn’t want to return home empty-handed, so he decided to stay in Russia — “not by choice,” as he puts it.

“At first I worked illegally at a ski resort. Mostly we chopped firewood and cleared snow around the cabins. They paid us in cash,” he says.

Two months later, Bilal moved to Moscow and obtained a patent — the work permit that allows citizens of visa-free countries to be legally employed in Russia. He found a job as a courier for Yandex.

Bilal speaks excellent Russian — something he says explains why, unlike many of his friends, he didn’t encounter xenophobia all that often. But conflicts still happened. “You’d run into people who’d say, ‘Migrants, coming here in droves…’ Especially when a customer had put down the wrong address and the delivery got messed up — somehow it was always the migrant’s fault.”

Bilal left Russia two months before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. “Back then it wasn’t like it is now,” he recalls. “Yes, the police would stop you on the street, but they’d take some money and let you go. Now my friends talk about Amina (a Russian mobile app for monitoring migrants), about police rounding people up, and about being sent to the war.”

He decided to set his sights on Europe instead.

Watched and bullied

In Russia, the path to legal employment for migrant workers runs through a processing centre known as Sakharovo — located about 60 kilometres from Moscow and notorious for its massive queues, where people often wait for hours. The perimeter is guarded by armed security forces, and inside migrants undergo procedures such as blood and urine tests to screen for “socially significant diseases”. Those who manage to obtain their documents can work legally, but that doesn’t protect them from future problems.

Russians often refuse to rent apartments to migrants. Schools and kindergartens decline to accept migrant children, citing “lack of space,” while the adults themselves face workplace “raids” or frequent “document checks” on the street or on public transport. Even Russia’s war in Ukraine has become a tool for pressuring them: many migrants are pushed to join the military in exchange for various “bonuses,” such as fast-tracked citizenship.

After the attack on Crocus City Hall — which authorities say was carried out by four Tajik citizens —the security services launched large-scale raids. Tajikistan’s government, fearing a surge in xenophobic incidents, even advised its citizens not to leave their homes.

Lawmakers soon joined in. Over the past year, they have restricted the ability to obtain residency through marriage, granted the Interior Ministry the power to deport migrants without a court ruling, required migrant children to pass a Russian-language exam before being admitted to school, and created the Registry of Monitored Persons — a database of foreign nationals who supposedly lack legal grounds to stay in Russia. There are already known cases of people being added to the list by mistake, and effectively losing the right to move freely around the country after their bank accounts were frozen, and their driving permits revoked.

Officials have justified all these measures as necessary to fight illegal migration and prevent crime. In July, the Interior Ministry reported a rise in crimes committed by migrants, but migrants still make up only a small fraction of overall crime statistics. A study by the “To Be Exact” project found that adult Russian men are statistically more likely to commit crimes than migrant workers.

On September 1, a new pilot project went into effect: migrants from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Moldova, and Ukraine who are living in Moscow or the Moscow region must install a mobile app called “Amina.” Authorities openly acknowledge that the app’s main purpose is to continuously track users’ locations.

The app that doesn’t work

If a phone fails to transmit location data to Amina for more than three working days, the participant is automatically removed from the system. If the migrant cannot fix the issue quickly, they risk being added to the “monitored persons” registry — which can lead to frozen bank accounts, job loss, or even expulsion from university.

Imran, a 27-year-old Tajik citizen, is worried: “Location services on my phone are on, and Amina shows that everything is being transmitted, but several times a day I get notifications saying the app isn’t receiving my location. The app works terribly. And I have no idea what consequences this could have for me.”

Users report constant problems with Amina. Some can’t get past the first screen; others say the app won’t accept their photo; still others receive alerts that their data failed verification. But the most common issues are related to location tracking.

In comments on RuStore (Russia’s internal apps store), representatives of the developer respond that “specialists are constantly working to improve the app’s stability” and advise users to contact technical support. But migrants complain about waiting on the line for hours.

Anton Ignatov, the director of the Sakharovo centre, claims the programme will improve public safety and help “prevent violations by unscrupulous individuals”. He cites situations in which migrants buy a work patent — a permit to work — for a short period and then disappear “into the shadows,” “vanishing somewhere in the industrial zones of Moscow and the region”.

Such cases do happen, and the most obvious reason is money. Since January 1, the monthly payment for a work patent in Moscow and the Moscow region has been 8,900 roubles (about $115). For many migrants working in low-paid jobs — for example, in construction or warehouse work — this is a significant share of their income, pushing some into the informal economy.

Another factor is wage delays in the sectors where migrants from Central Asian countries most often work. Mukhammadjon from Uzbekistan, works on a construction site outside Moscow, hasn’t been paid in two and a half months. A month ago, he stopped paying for his patent — simply because he had no money left. He sees no tools to defend himself.

Employers, meanwhile, benefit from hiring such vulnerable workers: they can avoid paying social contributions, hand out wages in cash, and rely on employees who are willing to work overtime for low pay.

Getting a job is becoming harder

Kudaibergen, 32, from Kyrgyzstan, worked at a warehouse on the outskirts of Moscow — “to support my family”, he says. His employer provided hostel-style housing for migrant warehouse workers.

“OMON came to our building. They treated us like they were arresting dangerous terrorists. They showed up with batons and tasers, as if storming the place. They drove us all outside. We stood by the door with our hands behind our backs for about two hours while they checked everyone’s documents,” he recalls. “Some guys didn’t understand Russian well — it was very hard for them. If they didn’t understand something, they were beaten. […] Thank God, my documents were in order.”

Russian authorities typically insist that such inspections are carried out strictly within the law and that no unlawful actions are taken against migrants. As evidence, the Interior Ministry points out that migrants rarely file complaints with the police afterward.

As the new year approached — 2025 — the checks intensified, Kudaibergen says. Because of all the new rules and the overall treatment of migrants, he realized that working in Russia had become too difficult, so he returned home.

“But I still have to provide for my family,” he adds. “I’m thinking about Europe now. I ask friends and acquaintances how to leave. But I don’t know if it will work out. They say getting a visa is very hard.”

Gulnura, 35, a mother of three, had lived in Russia with her husband for more than ten years. In the spring of 2025, she flew with her children to her native Kyrgyzstan for a short break. Only after arriving did she learn about the new requirement obliging migrant children to pass a Russian-language exam in order to enroll in school. Her children speak Russian fluently, yet even before the rule change they hadn’t been admitted — schools said there were “no available places”.

“We originally planned to return to Moscow. But my friends who are still there complain that they can’t get their kids into school,” Gulnura says. “One friend has been collecting documents since April, but the school won’t accept them. Another managed to get her child to the test, but after the exam they sent a rejection: ‘Your child doesn’t know Russian well enough.’ Her daughter was born and raised in Moscow, speaks Russian fluently, went to kindergarten and prep classes, reads and writes.”

“Requiring language proficiency provides a pretext for an already widespread practice of arbitrarily refusing to admit migrant children to schools across Russia,” says Sainat Sultanaliyeva of Human Rights Watch. “By depriving migrant children of access to education, Russian authorities are effectively taking away the life opportunities schooling provides. Banning them from school undermines long-term social integration, increases the risk of harmful child labour, and heightens the danger of early marriage.”

Gulnura decided not to return to Russia with her children. “My husband is still in Moscow for now. He’ll come when everything is ready here, when he has work. But we — me and the kids — we’ve come back for good. It’s become impossible to live there.”

A chance to get into Europe

Despite numerous accounts of migrants becoming disillusioned with Russia, it’s impossible to say definitively whether labour migration has decreased in recent years: the available statistics are fragmented, and data from different government agencies often contradict one another.

The picture is further complicated by the Interior Ministry’s decision to stop publishing key data, as well as several changes to the methodology of migration accounting, which make year-to-year comparisons unreliable.

In 2024, researchers at the Higher School of Economics concluded that labour migration to Russia had fallen to its lowest level in a decade.

Since then, the number of entries into the country has grown, but the average annual presence of legal labour migrants has remained stable at around 3–3.5 million — noticeably lower than in previous years.

Rossiyskaya Gazeta writes that foreign workers are less willing to come to Russia for two reasons: tougher migration policies and declining incomes. With the rouble’s depreciation, earnings in dollar terms have fallen by roughly a third.

Yet Russia still remains the most popular destination for labour migrants from nearly all Central Asian countries.

In second place for migrants from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan is Kazakhstan, where most work in construction, wholesale and retail trade, and various service industries.

Third is Turkey, where Central Asian migrants are employed in manufacturing — especially textiles and clothing — as well as construction, hospitality, and seasonal agriculture.

South Korea recruits migrant labor for factories, agriculture, construction, and the fishing and seafood-processing industries.

But for many — like Bilal, who left Russia behind — the dream is still to secure a job offer in Europe. In the end, he managed to do so through the same intermediaries he had relied on earlier, paying them $2,000, he says. They helped arrange an invitation from a logistics company.

“If you don’t have work experience in Europe, it’s hard at first to get a job with a good trucking company. There are bad employers who take advantage of newcomers not knowing their rights. They might underpay you or force you to work overtime. At the same time, the police keep a very close eye on work-and-rest rules and can fine you, so nobody wants to break the law. By law, if your driving time is up, you have to stop and rest,” Bilal says, recalling his first job at a Slovak company.

After gaining some experience, he moved to another company, where he now earns around €2,500 a month.

According to the International Road Transport Union (IRU), more than half of European transport companies cannot expand their business because of a shortage of qualified drivers. Across the EU, Norway, and the UK, more than 233,000 truck drivers are currently required. The crisis is deepened by the fact that the profession is aging rapidly, and young people are not drawn to it, despite decent pay.

Ukrainian citizens once made up a significant share of long-haul drivers in the EU, but because of the war many had to return home for military service. In addition, some European employers terminated contracts with Russian and Belarusian citizens (or their visas weren’t renewed), forcing them to return home as well.

In Slovakia, where Bilal is officially employed, the shortage reached 12,000 drivers last year. As a result, the country simplified visa procedures for several nations — including Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Ukraine — for applicants willing to work in freight transport.

Poland actively issues work permits to citizens of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan; the Czech Republic attracts workers from Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan by fast-tracking work visas; Lithuania also issues visas to those seeking jobs as drivers.

In 2023, the number of first-time work permits issued in the EU to citizens of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan rose by 30%, 39%, 50%, and 63% respectively compared to the previous year.

But Bilal believes that even with the current labour shortages, getting into Europe from Central Asia is still far from easy. “If you don’t have people here who can recommend you to a company, it’s a difficult process for ordinary working people,” he says.

All the more so because public frustration over migration has been growing across Europe in recent years, pushing some governments to tighten rules for third-country nationals — even in sectors suffering from labour shortages.

Bilal likes living in Europe. He’s satisfied with the good pay and the way people treat him — especially Italians and the French.

He describes his job as demanding. “We spend more time away from home than at home. Years go by, and people hardly see their families,” he says.

Bilal himself doesn’t yet have a wife or children. In a few years, he’ll be eligible to apply for permanent residency in Slovakia, but he hasn’t decided whether he’s ready to spend his whole life driving long-haul trucks across Europe.

*The protagonist’s name has been changed at his request. With contributions from Almira Abidinova and Aisymbat Tokoeva. Read this story in Russian here. English version edited by Jenny Norton.