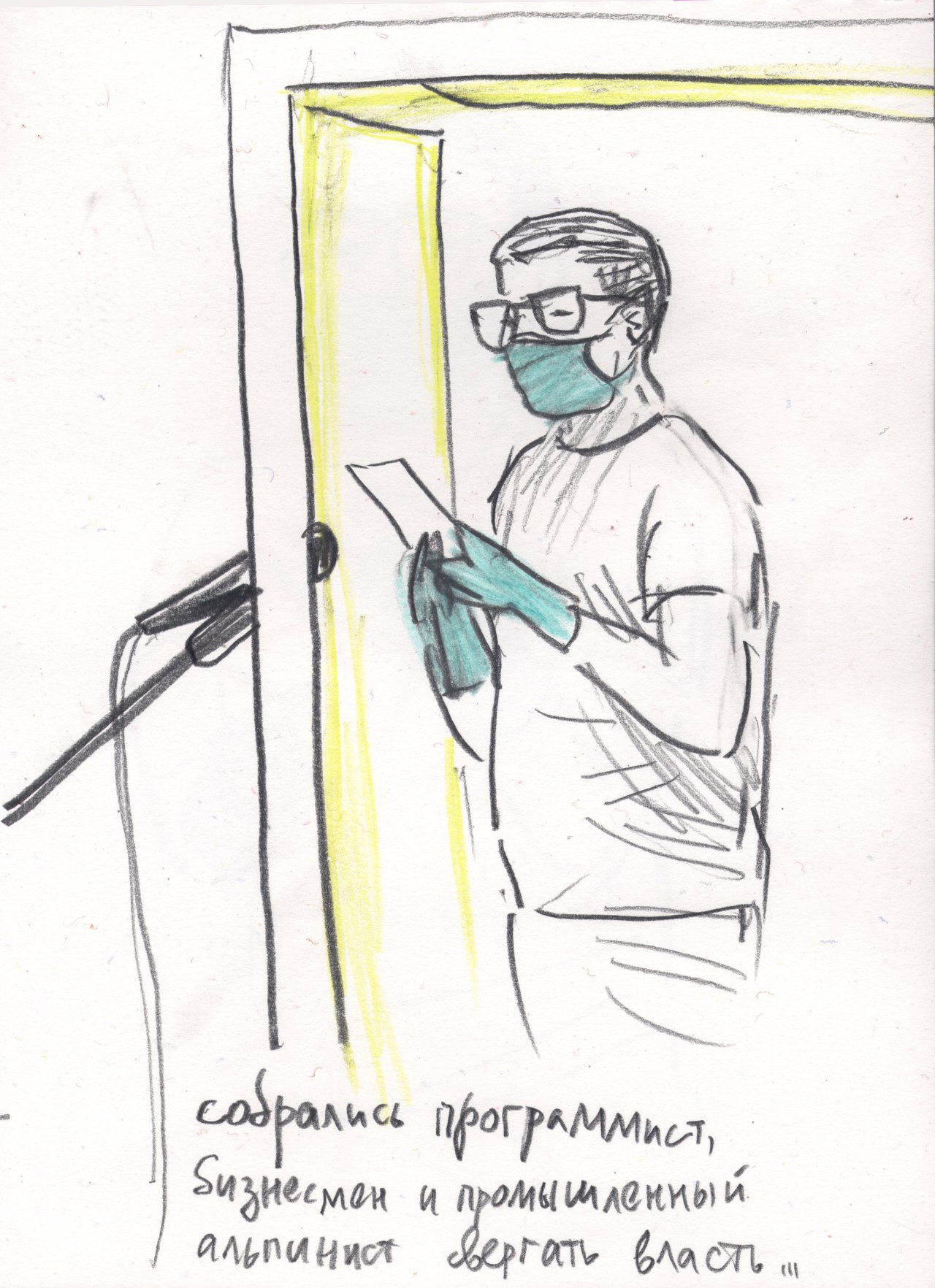

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

משנכנס אדר – מרבים בשמחה

When Adar begins, joy multiplies.

I. Equality

Joy multiplies in the month of Adar. Joy arrives in the month of Adar. Why, oh why die in March? Spring is just around the corner. The darkness and cold have almost retreated. The light, like water, comes every day. To get out, clamber out from under myself as from under falling debris and beams, to shed myself like old scales. To fly, race, and run away from this exploding ruin. It is the snow melting. It is me melting. Joy surges. Joy arrives.

A friend told me in passing that joy is multiplied in the month of Adar. (Who multiplies it? Why does she do it? How does she do it?) I had always felt this poignantly, you know. At the beginning of March, on the fault line between winter and early spring, Grandmother died. During a lecture, someone from the dean’s office came to get me. They said the ambulance brigade medics who took her to hospital had been looking for me. When I arrived, she was still conscious but shrieking in pain. She asked for a shot that would make her die more quickly. Her aorta had burst. We managed to talk. I said, “Hang on, Granny. If you want, I’ll give you great-grandsons, Granny.” But she said, “March, damn March.” Her aorta had swollen two years earlier. Then, on the dawn of March 23, the police had rung the doorbell and asked whether there were any men in the house. The bed was empty, and Grandmother had dashed to the door and fallen down in the hallway. I rushed downstairs.

Very slowly and instantly, very slowly and instantly. She lay in an unbuttoned black overcoat over white panties, her t-shirt hitched up, her skinny yellow hand strangely twisted. A dent on a car. She had hit something before crashing to the ground. There was almost no blood, only a small spot near her head, and two teeth knocked out. Mom.

A negative imprint on icy pavement. An instant plunge into the abyss of the Mariana Trench. Why did you dress up as blackbird? Where are you taking me, Mother Death?

The sky’s light light light light fills floods the whole world. The sky is coming, the sky flows in like the ocean’s tide, the sky is huge, immense, and all the houses, cars, the entire dusty city, the people come undone from the earth and float in the sky like tiny flakes of yesterday’s pain, which has negotiated winter’s afflictions. Blinded by the light, consciousness bursts open toward the future, surrenders to the whirlpool of happiness, omnipotent, ready to face life’s trials and challenges.

“If we turn the IV off, she’ll die at once. If we don’t, she will be conscious for several hours or days,” the doctor said.

“Turn it off,” I said. I was eighteen.

When I left the hospital, the sky was shining, and the wind blew all the sails towards the sunset’s golden-pink clouds. I asked them that, before I got home, Grandpa’s Parkinson’s would progress to the point he would not realize he and I were alone.

Tattered thoughts rush past, shreds of memories sweep past. I don’t have the time to write them down, connect them, grab them.

You drew the line. You established the border. You will not let me into your house, your family, your life. During days of universal joy, all I can do is sit glued to the screen in solitude, peering at social network timelines where photos of your warm family festivities light up. I am hungry with envy and sadness, a tramp standing outside Yuletide windows.

I have become your illegal alien. Everyone knows about me, but they try not to notice me. You forbade taking pictures of us together, and in conversation you hide my presence with the singular. I shouldn’t leave the house too much. I should be invisible, inaudible, and inconspicuous. It should be as if I didn’t exist. I shouldn’t exist.

Clouds like ragged threads sweep across the blinding sky.

In March, the city really reveals itself only to the drunk and the desperate, to people standing on death’s windowsill. Only through the inward tears produced by the splinters of an ice floe smashed to smithereens does it flash with a hallucinatory beauty for an instant, and the first person you meet passes through the hell of a bulging heart like a thread through the eye of a needle.

My gaze crashed into you as I measured the distance from the balcony to the pavement. You lay, your head nestled against the belly of another person, lying on their back, the whites of their eyes spinning in oblivion, under my balcony. You were trying to warm yourself in the other person’s warmth or just die together. I was afraid to touch your squashed fingers, dried blood, dusty clothes, and urine-stained clothes. I told you to get up on your own and, holding onto the wall, walk with me to the front door. When we got there, before you could tell me about your eight-year-old daughter Liza and your mother in Orenburg Region, whom you had managed to send five thousand rubles before, and before I could decide whether to invite you into the flat so we could jump together or remember how to call the ambulance and where to find the address of the homeless shelter, we sobbed for a long while on the dirty front stoop, random and nameless.

It takes two or three weeks for someone who ends up on the streets to turn irretrievably into a homeless person, the same amount of time depression becomes clinical.

You are afraid of letting me in, because you know that as soon as I cross the threshold, your home will be inundated with the stench of misery and insanity. You are afraid to defile the peace of your home and loved ones. You are afraid the walls will immediately crack, and the infection of homelessness will spread to everyone. You have marked out your domain.

The pink pill rolls around inside you. It smashes you into the pavement.

Bright pink clouds lashed the eyes and scalded the brain of the body on the bloodless balcony.

The balcony can fit exactly three people. It resembles a tiny boat, a cradle careening between streams of cars and the sky. I suggested we go live there, never going back under the roof. Three wise men in a tub. Bas Jan Ader in the midst of the Atlantic. Baron Munchausen, pulling himself from the water by his own hair to fling himself into the sky’s blinding abyss.

I searched for you up and down the area around Dostoevskaya subway station, in all the attics and cellars, in the unlocked entryways and the warm spaces between the doors into the subway. In your crevice between peeling moldings and the cast-iron curls of stairway railings, all that was left of you was rubbish: a bed fashioned from crumpled newspapers and the booklet with addresses of homeless shelters I got for you the other day. We were going to meet right after the weekend. I was going to bring you clean clothes and wet wipes so you would look decent when you went to get new papers and register with the social services.

When, a few weeks later, I accidentally stumbled upon you trying to bum a cigarette, you were either completely drunk or distant. I handed you a cigarette and tried to figure out where you had been sleeping and when we would go to the homeless shelter. You could not focus and mumbled, “What they call you, sweetie?” I realized I was too late. You had already sailed away. You were already out there, furrowing the waves of the ocean in search of the miraculous. Neither your daughter Liza nor your grandmother would ever see you again. You had left your grandmother and left your grandfather. You had sailed away from me, leaving me alone with my own salvation, you smarted-ass jerk, Slavka.

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

II. Fraternity

In moments of the most terrible despair, I imagine I have a twin brother. He is just like me, only a little different. He knows everything about me and understands me. He is the only person around whom I can cry, and to whom I am not ashamed to complain. I imagine he comes and comforts me.

We stretch our hands in the sun and laugh with joy. They are exactly the same, only slightly different colors. We have equally thin wrists and large palms with wide, seemingly broken joints and thin fingers. The hands of twins. We are different sexes, but we cannot help but find similarities in our absurd, adolescent-like bodies. Your hair is curly. Mine is straight. But we have an intangibly similar, perpetually disheveled look. My found brother.

“Sister,” said a guy sitting outside a shop and holding a dirty cap turned upside down, “Sister, some change, please.”

The noise of the lagoon gently beat against my eardrums. The sun shined, and almost without splashing the fullness of happiness, I walked by him schlepping full bags.

“I can’t go back. Everything is destroyed. I have burnt all my bridges. If you knew what it cost me to get here, what it cost me to live through this break-up—”

“Calm down. This no place to have a tantrum. Listen to me. You cannot stay. It’s impossible.”

“I laid down my whole life to get here. I scorched the past from my heart. I cut myself off from everyone.”

“It’s impossible. It’s written here in black and white. The decision on your application is negative. Where are you going to live? On the streets?”

“I’ll think of something. I have nowhere to go. I ask you to reconsider the decision.”

“You have gone through all your appeals. There is no room here for all of Africa. It’s an unbearable economic burden on our taxpayers. They cannot feed everyone.”

“I can work.”

“There’s been high unemployment here for many years.”

“I’m not afraid to do any job.”

“Even if that’s so, you’ll never really be accepted here. The culture is different.”

“I’ll learn the language. I’ll come to know your culture. I’ll become a different person.”

“Enough! Stop it! What use is any of this to us in the long run?”

I don’t know how much time has passed since I was dragged from the sea. I don’t remember being brought here. The days, weeks, and months have passed automatically, without feelings and sensations, leaving no memory of themselves, as if the cold tons of water that had squeezed me inside and outside had paralyzed my mind. As if a half-dead body had been pulled out, but what was alive in it and made it want to live had been too late to save.

I just up and went outside one morning. I walked down a street and found myself on the embankment of a wide channel or strait between islands. I felt the sun’s tender caress and smelled the seaweed. The green water picked through the shallow waves and, half asleep, smiled to no one and everyone all at once, and coral houses stood petrified and solemn along its rim. This beauty, these sounds, and the gentle warmth struck me with such force I couldn’t stand it. I fell, tensing my body, hiding my face, and closing my eyes. I suffered convulsions, and tears flooded my head. I remembered everything. Fear, hunger, a series of deaths and partings, no hope of meeting again, loneliness, despair, an endless trek, fear, fear. A mad hunted beast consumed in the depths of itself. Not everything was connected. Here and there, now and then were endlessly, unbearably separated. This could not be happening in one world; this could not be happening to one person. I had died. I was dead.

I tried to open my eyes again. On the other shore, half-turned towards me, a brick-red building with two candle-thin towers and a rounded dome floated, its white marble façade looking back at me. Four light figures—three above the forehead’s triangle and the fourth at the very top of the dome—soared from the building into the sky. Stunned by the building’s unprecedentedly simple shining grandeur, I again hid my face. Il Rendetore, Il Rendetore. Whether I had died or survived, I realized one thing: I was saved.

I don’t mind. They can work on construction sites, in closed facilities. As long they don’t plague us with their presence. I definitely don’t want my children to see them.

Why has it become so difficult? Why do I feel such horror when I imagine it? Is there something wrong with me? Can’t I leave the house like everyone else? Can’t I go where I want, like everyone else? How silly! What nonsense! I will come and say hello to everyone, as if nothing has happened. I’ll be cheerful. I’ll laugh, make jokes, and chat, hopping from topic to topic. I have been repeating this for many days. I smile to myself in the mirror. I turn on the most upbeat music. I walk along, my head lifted, a spring in my step. I’m like everyone. I’m like everyone. My heart beats harder. But here is the door. It’s not even locked: you just need to push it. No! No! It’s easier to plunge into the abyss. An ostrich in a cage, its head bumping against the ceiling. A lion cub’s severed head. Huge pumpkin halves floating in the water.

Meat carcasses. Everywhere there are meat carcasses and flies, flies, flies. If you do not come up to me first, if you are not by my side, everything will instantly fall silent, all gazes will pierce and immobilize me. Someone’s hand will pull on the end of my smiling turban, my cocoon—and I will be confronted by everyone, my face bare and frozen with animal fear.

“Can I ask you something? Do you have a boyfriend?”

“What does that have to do with anything?”

“I just like you.”

“Listen, I’m helping you defending your human rights, and you’re flirting with me?”

“No, no, I’m not flirting. I’m serious. I want to marry you. I sent my parents a photo of you and wrote to them you are a very good girl.”

“You’re serious? Serious is not receiving refugee status and getting sent back to a war zone. Or, at best, you stay here without papers. You’d better think about this seriously.”

“Yes, yes, I know you’re right. It’s very important. You have helped me so much. I thank you from the bottom of my heart. But everyone needs someone to be close to. Everyone needs a future in common with someone else.”

“It is natural for people to guard the borders of their house,” intoned a voice on the radio, and I could not come in to see you. Even if I had gone in, the door would simply have moved farther away and remained locked. Then my feet carried me down the stairs, flight after flight, into the courtyard, into the streets of the city to walk to the point of oblivion, until my senses were numbed, until I had lost the ability to speak, until I was anesthetized by the night’s cold.

When I was told we could have no future, that my face must be deleted from all photographs, and my name must never be said aloud, all mentions of it must be effaced and it must be forgotten, when you repeated it, and everything was on the point of collapse, I decided to save our incredible love, our unlimited intimacy in the past. We set out deep into the past. We retreated farther and farther from life, reeling through generation after generation, descending ever deeper into the branched roots of our family trees. We explored each and every fork and knot, looking for a possible intermingling, for the dead man who would silently proclaim, “I now pronounce you brother and sister.”

I don’t know how long I wandered the streets, squares, back alleys, and filthy, luxurious building lobbies, but once, when I came to my senses, I realized I was in a completely different time and city. It was phantasmagorically beautiful, but quite different from my bitter city, where beauty is spread in a thin layer over a flat space, like butter on a perestroika-era sandwich, the neoclassical columns-cum-commissars dispense an equal dose to each, and only needle-like spires are permitted to pierce the sky’s blue vein. Here, on the contrary, beauty exuded from every crevice, clambered over its own head, shook its stone lace, and doubled in the canals, leaving the eyes with not a centimeter of peace. Incredible churches squeezed between beautiful buildings, tucking in their apses. On one of the tiny squares, two blinding, blocky marble façades suddenly rose over me. I watched them, transfixed. They seemed to grow against the black sky. Then they toppled down on me with all their luxury, all their unbridled splendor, and I cried out in amazement, horror, and resentment, mortally offended for all the dull bedroom communities, the settlements consisting only of Khrushchev-era blocks of flats, plopped down in the middle of swamps, the shanty towns, jury-rigged from planks of old plywood, tarpaper, and filthy quilts, where homeless people and Roma children took shelter, mortally offended that beauty was so unfairly, so unequally dispensed.

I rushed through the intersections of an endless latticework of streets, running into dead ends and stumbling over bridges until, finally, at dawn, the sun glanced between the houses. I came to a wide embankment. In the rays of the rising sun, over the surface of waters forced apart, a clear Palladian silhouette arose, turning slightly to greet the arriving joy. Something dripped, thawing from the inside, painfully easing the winter frostbite. I realized the month of Adar had passed, and I had been able to survive the year. The time and place came into focus. It was April, my mom’s birthday and, maybe, mine, and I was ten years younger than she was when she jumped from the balcony. I stood on the same embankment where, several centuries ago, during the plague, the incurably ill were dragged so that, for the last time before they headed to the cemetery, they would believe in salvation.

Pateh Sabally, a twenty-two-year-old Gambian man, tried to stay afloat in a canal while onlookers shot him on video, peppered him with racist remarks, and laughed. In one video, you can hear the onlookers screaming at him, “Go on, go back home.”

At least three life rings were thrown into the water, but Sabally did not try and reach them, which suggests he committed suicide.

No one jumped into the water to help Sabally, and he drowned.

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

III. Liberty

Remember, when we embraced for the first time, everything fell into place, everything was as it should have always been. The planets no longer had to orbit the sun. They finally had come home. They had found their safe haven. You wove me a cocoon of tenderness from kisses, words, and touches. It will protect me always and everywhere. And if you are with me when I die, I will die happy.

But only you and also you were blinded by pain at the same moment.

Dost thou remember, do you remember, how on that morning, when we awake together, embracing, and laugh at the joy of feeling each other, the happiest day will dawn? Everyone will share love with everyone else, and there will only be more love. Fear, jealousy, despair, barbed wire, and checkpoint politeness will be left behind. All the homeless, insane, undocumented, illegal and semi-legal, prostitutes, mistresses, and street urchins will stand straight up and solemnly along the sunny streets, and everyone else, giddy, will rush out to them, leaving their homes forever. Smiles will crack immured faces, and the age-old plaster of affliction will spill onto the ground and people’s clothes. The wind will waft the dust away. The buds of joy will burst open with a crash and sprout through every creature. And the joy keeps on coming and coming and coming. We multiply the joy.

Dost thou remember? And thou? Do you remember? Do we remember?

Originally written as a personal letter by Olga Jitlina, although this text never achieved its aim, it was the basis of Fraternité, an audio walk round Venice in October 2017. Curated by Vera Kavaleuskaya and Alina Belishkina, the walk was part of Research Pavilion: Access to Utopia. Illustrations by Anna Tereshkina. Translation by Thomas Campbell. A huge thanks to Ms. Tereshkina and Ms. Jitlina for permission to reprint their work here.

Anna Tereshkina. Photo by Anastasia Makarenko. Courtesy of Ms. Tereshkina’s Facebook page

Anna Tereshkina. Photo by Anastasia Makarenko. Courtesy of Ms. Tereshkina’s Facebook page Anna Tereshkina, Self-Portrait. Courtesy of the artist

Anna Tereshkina, Self-Portrait. Courtesy of the artist

A scene from the courtroom in Petersburg: Yuli Boyarshinov’s lawyers are in the foreground.

A scene from the courtroom in Petersburg: Yuli Boyarshinov’s lawyers are in the foreground.

Defendant Yuli Boyarshinov’s closing statement was so short that artist Anna Tereshkina didn’t have time to finish her sketch.

Defendant Yuli Boyarshinov’s closing statement was so short that artist Anna Tereshkina didn’t have time to finish her sketch.

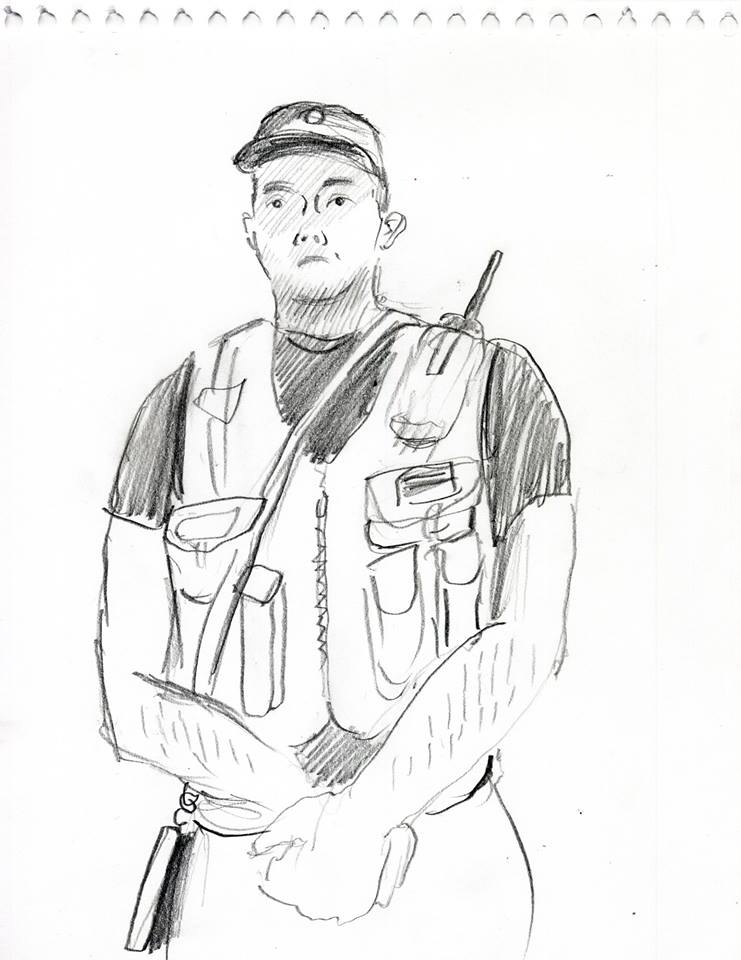

Viktor Filinkov’s defense team: Yevgenia Kulakov and Vitaly Cherkasov

Viktor Filinkov’s defense team: Yevgenia Kulakov and Vitaly Cherkasov

“I have every grounds!”

“I have every grounds!”

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018 Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018 Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018

Image © Anna Tereshkina, 2018