Ivan Astashin in prison. Photo by Maxim Pivovarov. Courtesy of RFE/RL

Ivan Astashin in prison. Photo by Maxim Pivovarov. Courtesy of RFE/RL

“The FSB Are the Main Terrorists”: The Political Biography of Ivan Astashin

Dmitry Volchek

Radio Svoboda

October 3, 2020

On the night of December 20, 2009, the eve of State Security Officers Day, a group of young people threw a Molotov cocktail into the FSB’s offices in Moscow’s Southwest District. No one was injured, and the room was slightly damaged: a windowsill and several chairs were burned. A video of the protest soon appeared on the internet, entitled “Happy Chekists Day, Bastards!” The author of the video was 17-year-old Ivan Astashin.

The arson sparked a large-scale, trumped-up criminal case against the so-called Autonomous Combat Terrorist Organization (ABTO), which was headed, according to investigators, by Astashin. Initially, the alleged members of ABTO were charged with property damage, but soon they were also accused of disorderly conduct. The Investigative Committee later decided that the defendants in the case had wanted to impact state policy, so they should be tried for “terrorism”(as punishable under Article 205 of the criminal code). They were tortured into confessing.

Ten young people were involved in the ABTO Case. In 2012, they were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment. Astashin received the longest sentence—13 years in a high-security penal colony, which was later reduced to 9 years and 9 months. Astashin was first sent to Krasnoyarsk Correctional Colony No. 17, but in 2014 he was transferred to Norilsk Correctional Colony No. 15. Lawyers and human rights activists argued that the case was political, pointing out that ABTO did not exist, and the members of the alleged “terrorist organization” did not even know each other.

“In Ivan’s case, the FSB took revenge on teenagers who dared to throw a bottle of petrol through their window. The case was a bellwether. It showed how the security forces had degenerated: why should they stake out real criminals and document their every move, if they could torture children until they lose consciousness, forcing them to sign a horseshit ‘confession’ that will then be called ‘evidence’ in the verdict?” said lawyer Igor Popovsky, who argued Astashin’s case before the Russian Supreme Court.

In recent years, Astashin has become known as an op-ed writer, penning articles about prison mores. On September 1, 2019, Radio Svoboda published his letter “Breaking Convicts Under the Law’s Cover,” which detailed the injustices at Krasnoyarsk CC 17, about the differences among castes of prisoners, their collaboration with wardens, and the psychological coercion employed on prisoners by correctional officers. We soon received a response from the penal colony’s wardens that Astashin had not written the letter and that no violations of the law were permitted in the colony. Although we knew that the letter had been written by Astashin, we took down the article, fearing for his safety.

On September 21, 2020, Astashin completed his sentence and was released. He is currently working on a book about his prison experience. He told Radio Svoboda about what happened to him on the outside and in prison.

Your comrade Alexei Makarov said that he became a revolutionary when he was 15 years old. When did you get interested in politics?

When I was about 14 years old. And it all started with a nationalist agenda. There were violent clashes between [ethnic] Russians and Caucasians in Kondopoga [in 2006]. I looked for information and in early 2007 I joined the Movement Against Illegal Immigration (DPNI).

When they called you a nationalist in court, were they right?

At first I was a nationalist, then my views expanded. I left DPNI and in 2009 joined The Other Russia coalition, which at that time was led by Eduard Limonov, Mikhail Kasyanov, and Garry Kasparov, and it included nationalists, liberals, communists, and anyone else you can think of. In the same year, 2009, I visited Ukraine, where I got acquainted with the movement of autonomous nationalists, and I thought that we should do something like it. At that time, there was a split in The Other Russia coalition, everything there came to a grinding halt. My radicalization occurred because there were no people organizing above ground. Then there was the movement of autonomists in Russia, both nationalists and left-wing anarchists. Direct action against the police began: police departments and police cars were torched. I also thought that we should do something like this. At that time, I felt like a revolutionary. I was 17 years old, and we decided to hold a protest action against the FSB.

You made a video of the action. It is still accessible on the internet, and there is a slogan “Russian action.” So, this was a nationalist protest?

Yes.

Do you regret it or recall it with pleasure?

Neither one nor the other. I don’t regret anything: what’s done is done. At the same time, I now believe that it was ineffective: the protest’s efficiency rating was negative. We had wanted to draw attention to the dictatorship of the Chekists, but [the video had] ten thousand views, which is a drop in the ocean. It did not spark a public discussion, it was all a big waste of time. Meanwhile, the people involved in the protest received long prison sentences. Of course, these were ineffective actions.

You were also accused of trying to blow up a Lexus. Whose car was it?

That was a stupid story. As a chemist, I experimented, I was interested in pyrotechnic devices and explosives. I built this thing and decided to test it. I found a Lexus: I thought it was probably insured. That’s another social subtext.

Attack the rich?

Yeah.

The investigators claimed that you were the leader of an organization that consisted of about ten people. Who were these people?

Guys I knew, but not all of them. They also carried out direct actions: seven arson attacks. The only thing we had in common was that we were acquainted. We were tortured into confessing that we had collaborated. If you read the verdict carefully, there are many inconsistencies. They write that the guys saw a police department and decided to torch it. But why do they then write that I was in charge of the action? Nevertheless, we were tried as an organized criminal group: everything those guys did I was charged with as well, and I was convicted as the organizer.

But did you know of ABTO’s existence? And did the organization even exist?

It was during the investigation that I found out that I was the head of the organization. And I saw the videos that they posted on the internet. Neither they nor we had any organization. The person who posted the videos just decided that it would be more interesting if he wrote that it was some kind of organization. It was four people going round setting fires.

Are the Network and New Greatness cases similar to what happened in the ABTO Case, or have the methods of the Chekists changed over the last ten years?

They are very similar, only worse. We were arrested for real actions. There was no terrorism in our case, but there were actions: they can be qualified as property damage or disorderly conduct. In the Network and New Greatness cases, there were no actions at all, that is, they were tried simply for belonging to mythical organizations. The laws that are now used to judge the defendants in those cases simply did not exist in our time. If we were tried now, we would probably be given twenty years in prison. All those articles [in the criminal code] are getting tougher and tougher, and the cases are now tried by special military courts. In addition, now there is the Rosfinmonitoring list [a financial stop list of “extremists” and “terrorists”], plus probation until your conviction has been expunged from your record. It’s easier for [the security services] to work in this way, because they don’t have to wait for someone to set something on fire, they can just take some guys who behave the wrong way, talk about the wrong things, or look the wrong way, and whip up a nice terrorism case, and get awards and promotions.

Ivan Astashin and comrades holding a rally on Chekists Day, on December 20, 2009, on Triumfalnaya Square in Moscow. Their banner reads, “The FSB are enemies of the people.” Courtesy of Ivan Astashin and RFE/RL

Ivan Astashin and comrades holding a rally on Chekists Day, on December 20, 2009, on Triumfalnaya Square in Moscow. Their banner reads, “The FSB are enemies of the people.” Courtesy of Ivan Astashin and RFE/RL

I read the article in which you write that the FSB are the only terrorists in Russia.

Yes, I wrote that, because terrorism is defined in the criminal code as various actions (not necessarily explosions and arson) intended to frighten and intimidate the populace. And who is intimidating the populace now, other than the FSB? We have other security services, but they are also dependent on the FSB. You know, when I carried out the action against the FSB, I really didn’t fully understand what kind of an organization it was. I understood that they had a lot of power, that the country was actually a Chekist dictatorship, but I had no idea how big it was. Even ordinary cops shake in their boots when FSBniks show up. The doors to all government institutions are open to the Chekists. All civil servants, judges, and MPs obey them unquestioningly. That’s why I called the FSB the main terrorists.

Did FSB officers visit you in the prison camp and threaten you?

Yes, that was in 2015. As usual, they did not introduce themselves, but only mentioned that they had flow in from Moscow: I was serving my sentence in Norilsk at the time. They were interested in what I was going to do after my release. I said that there were five more years until the end of my sentence, and I didn’t know yet what I would do after my release. They told me something to the effect that I shouldn’t get it into my head to engage in any political activity. Not that they directly threatened me, but they mentioned that even if I went abroad and mad trouble for them there, they would still get to me.

How did ordinary prisoners perceive you? As a hero or as a weirdo whose motives were impossible to understand?

Differently. There really were convicts who would say, Well done, cool, they need to be burned. There were also who thought it was odd: you’ve been sent down for ten years, what was the point?

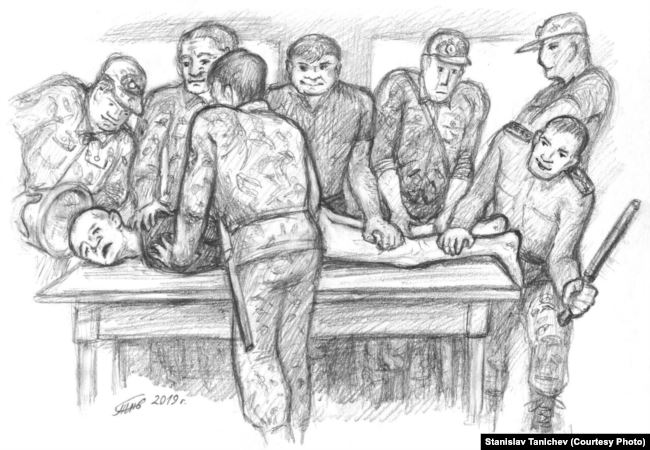

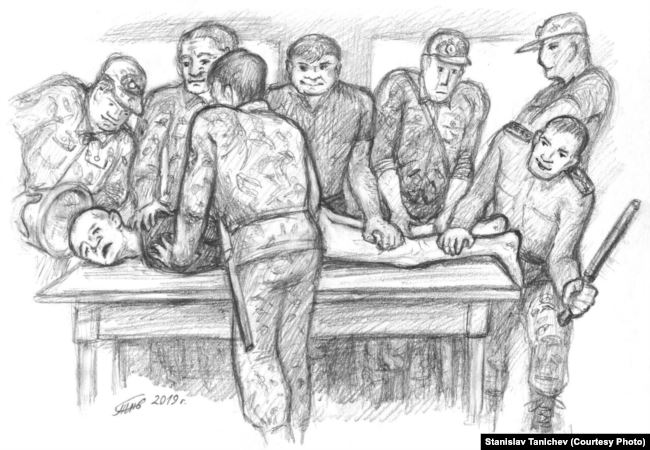

Drawing by Stanislav Tanichev. Courtesy of RFE/RL

Drawing by Stanislav Tanichev. Courtesy of RFE/RL

You said in an interview that you saw all of Russia in the Siberian prison camps. What have you learned about Russia? Is it ready for the revolution you dreamed of?

Many people living in Moscow have no idea what is happening beyond the Moscow Ring Road, how people survive on a salary of 5-10 thousand rubles [a month; meaning between 55 and 110 euros, approximately]. They often live on the outside according to the same concepts as they do in prison. As for whether they are ready for revolution, that is a difficult question. Many people just can’t imagine that things could be different. There is the famous question: who [will be president], if not Putin? Indeed, many people have this notion in their heads.

Did you meet Putin fans even in the camps?

Yes.

Were they outliers or were there many of them?

The ardent Putin supporters were outliers, of course, but I would often hear people say that Putin was doing a great job: he’d lifted up the economy, whereas in the nineties there had been nothing to eat at all. But now the situation is moving away from Putin. Meaning that, whereas in 2014 everyone got behind “Crimea is ours” and Novorossiya, and sometimes a couple of prisoners would argue with several dozen [Putin supporters], but now they mostly chew out Putin’s policies.

Even in the Siberian camps in 2014, there was a patriotic upsurge and people were happy about the annexation of the Crimea?

Yes, but then the situation changed, and the whole upsurge fizzled out.

Last year, we published your letter about the situation at the Krasnoyarsk colony, and then the wardens demanded that it be removed: allegedly, you were not the author. We took it down so you wouldn’t get hurt. What happened to you then?

It was unexpected. It is clear that if you are institutionalized and you write something negative about the institution, then, of course, there will be a reaction. I was in Norilsk, describing the general practices that had developed in the prison system, and I mentioned the Krasnoyarsk camp as an example. And they got so upset! They made threats, very clear threats. In Krasnoyarsk Territory, there is Remand Prison No. 1, known for its torture cells. There is a regional tuberculosis hospital where convicts are absolutely illegally injected with the strongest psychotropic drugs. And when I was summoned for a chat about the matter by the head of the prevention and enforcement department [of the penal colony], he made it clear what could happen to me in the future. I know such stories about how a person wrote complaints about the wardens, and then he was taken to these places of torture, and then the person recanted his testimony while being videotaped. I knew that something similar could be done to me. I had to write the document that your editors received. Of course, when I wrote it, I really hoped that they would understand the situation.

Of course, we understood, but we were afraid for your safety and took down the article.

I was hoping they wouldn’t remove it. Both there and through the convicts, they tried to get to me, and for some time the email server was disabled, and the warden, when he went on rounds, made it clear that it was all because of me. Then I found out that I was to be transferred. Initially, there was information that I would be taken to that hospital in Krasnoyarsk. I had already been given to understand via the convicts that they could take me through the torture remand prisons there. Consequently, everything followed a completely different scenario: I was transferred to CC 17, which I had just been writing about. I was transported without any untoward happening to me. I arrived at the transit and transfer prison, and everything was cool: not a word was said about the situation. I was there for four days before arriving at CC 17, where the deputy warden said to me on my first day, “I know why you have been brought here. I don’t care about that article. Let’s put it this way: you are now going to quietly finish out your sentence, and you’re not going to create problems for me, and I’m not going to create problems for you.”

Did your other articles about life in the prison zones go unnoticed?

The others were also noticed, but there was a fairly calm reaction to them. At one time, there was a special field officer in charge of working with “extremists” and “terrorists,” and he sometimes called me in to say he’d read my articles.

I’m sure you met other prisoners convicted on similar charges.

Yes, there a lot of people convicted in high-profile cases in Krasnoyarsk and Norilsk. When I arrived at CC 15 in Norilsk, there were quite a lot of people who had been convicted under Article 205, but mostly they were people who had been involved in the fighting in the North Caucasus. When you read their verdicts you find mentions of [Chechen rebel commanders] Maskhadov, Khattab, and Shamil. And when I was transferred to CC 17 in Krasnoyarsk a year ago, I also saw quite a lot of people who had been involved in combat or attacks on security forces in the North Caucasus over the years.

Drawing by Stanislav Tanichev. Courtesy of RFE/RL

Drawing by Stanislav Tanichev. Courtesy of RFE/RL

You rubbed shoulders in the camps with people of different ethnic groups living in Russia. Have you reconsidered the beliefs that moved you to become a revolutionary at the age of seventeen?

Yes, my views have changed. When I joined DPNI, I saw migrants as the problem, but over time I began to see the state as the problem. Migrants are not to blame for anything: they come here out of desperation, because their home countries are even worse than here, just as many people are leaving Russia for Europe now. In other words, these processes are quite natural. People of different ethnic groups and faiths can easily get along with each other. We just need competent policy to avoid conflicts. All this xenophobia is largely groundless. While I was on the inside, I read Robert Sapolsky’s Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, which examines why people are often biased against those who belong to a different race or ethnic group. If you get to the root of the problem, there is no reason for it. We need to think about what unites us, not what divides us.

I noticed in your interview with the BBC a reference to Vladimir Sorokin. Did you find something in common in what he describes with what you saw in the camps?

Yes, I love Vladimir Sorokin. One of the things that clicked with me was the idea of the new Middle Ages, as described in his novel Tellurium. I can say for sure that the Russian penitentiary system is the new Middle Ages. Here, in each region, there is a special way of life, which is shaped both by prison officials and prisoners, despite the fact that the law seems to be the same, and the codes prisoners live by is the same everywhere. In some places, prisoners live free and easy, while in others the wardens set up a totalitarian regime in the camps through beatings and torture, as, for example, was the case in Omsk before the riot there in 2018. In yet other places, the wardens and the pseudo-kingpins from among the convicts converge. There are unwritten rules, procedures, and forms of interaction everywhere. It really is the new Middle Ages.

Ivan Astashin with the artist Stanislav Tanichev, who illustrated his articles. Courtesy of RFE/RL

Ivan Astashin with the artist Stanislav Tanichev, who illustrated his articles. Courtesy of RFE/RL

You have now been released, but you remain under probation?

Yes. The law on probation was adopted in 2011. I was arrested in 2010, but in 2017, changes were made to the law such that all those convicted of terrorist charges must be placed on probation until their criminal record is expunged, which in my case is eight years. No one cares about you behaved in prison. Whereas earlier, repeat offenders and those who were deemed repeat violators of prison rules were put on probation, now everyone convicted on terrorist charges is put on probation, too. No one cares that I went to prison long before the law was passed. Logically, according to the Russian Constitution and international norms, the law should not apply to me. However, it applies not only to me, but also to other people in this situation. Restrictions are imposed on us: we have to check in at a police department between one to four times a month. (I’m required to check in twice a month.) You cannot leave your home between ten at night and six in the morning. I have filed an appeal against my probation and plan to bring the case to the European Court of Human Rights, as I believe that this practice violates the European Convention on Human Rights. A complaint on similar grounds, filed by one of the defendants in the Bolotnaya Square Case, Sergei Udaltsov, has already been communicated to the European Court of Human Rights.

You don’t want to leave Russia?

I don’t. Everything is bad in Russia nowadays, but there are a lot of areas where you can do something and change things for the better. Nor am I talking about politics in the literal sense. For example, there is human rights advocacy. In any case, no matter what the circumstances, no matter where I am, I will still do something to change society for the better.

• • • • •

This translation is dedicated to Vladimir Akimenkov, a former Russian political prisoner and prisoner rights activist who over the years persuaded me to pay attention to Ivan Astashin’s remarkable story. If you have the means and the opportunity, please consider donating to Vladimir’s fund for Russian political prisoners. You will find the details below. || TRR

Ivan Astashin and Vladimir Akimenkov, October 11, 2020, Moscow. Courtesy of Vladimir Akimenkov’s Facebook page

Ivan Astashin and Vladimir Akimenkov, October 11, 2020, Moscow. Courtesy of Vladimir Akimenkov’s Facebook page

Vladimir Akimenkov

Facebook

June 7, 2020

My Annual Birthday Fundraising Event for Political Prisoners

On June 10, it will be eight years since I was arrested as part of the Bolotnaya Square Case. Every year on this date I hold a fundraiser in support of the political prisoners with whom I am currently working.

Every year we meet live on my birthday to help political prisoners. This year, for obvious reasons, we will not be able to meet on June 10. We will definitely do this later, when we can get together without the obvious threat of getting sick. (The live fundraising event will be announced later, via a separate post and an update to this post.)

In the meantime, I am launching a remote fundraising event. In recent years, we have managed to find over 16.8 million rubles [approx. 186,000 euros] for people who have been politically repressed. Please chip in. We need to raise a lot of money. I don’t want to be broken record, but such are realities of Russian society.

Bank details:

— Yandex Money: https://money.yandex.ru/to/410012642526680

— Sberbank Visa Card: 4276 3801 0623 4433, Vladimir Georgievich Akimenkov

Bank details for ruble transfer:

Correspondence account 30101810400000000225

Bank BIC 044525225

Recipient’s account 40817810238050715588

Recipient’s Individual Tax Number 7707083893

Recipient’s full name AKIMENKOV VLADIMIR GEORGIEVICH

Bank details for foreign currency transfers:

SWIFT Code SABRRUMM

Recipient’s account 40817810238050715588

Recipient’s full name AKIMENKOV VLADIMIR GEORGIEVICH

You can send funds from one foreign currency account to another via the Western Union website.

If you send me a personal message, I can send you a final report on the funds collected.

Please share information about the fundraiser on different venues.

I’m worried about this fundraiser. But I believe in people.

Thanks.

Translated by the Russian Reader

Ivan Astashin in prison. Photo by Maxim Pivovarov. Courtesy of RFE/RL

Ivan Astashin in prison. Photo by Maxim Pivovarov. Courtesy of RFE/RL Ivan Astashin and comrades holding a rally on Chekists Day, on December 20, 2009, on Triumfalnaya Square in Moscow. Their banner reads, “The FSB are enemies of the people.” Courtesy of Ivan Astashin and RFE/RL

Ivan Astashin and comrades holding a rally on Chekists Day, on December 20, 2009, on Triumfalnaya Square in Moscow. Their banner reads, “The FSB are enemies of the people.” Courtesy of Ivan Astashin and RFE/RL Drawing by Stanislav Tanichev. Courtesy of RFE/RL

Drawing by Stanislav Tanichev. Courtesy of RFE/RL Drawing by Stanislav Tanichev. Courtesy of RFE/RL

Drawing by Stanislav Tanichev. Courtesy of RFE/RL Ivan Astashin with the artist Stanislav Tanichev, who illustrated his articles. Courtesy of RFE/RL

Ivan Astashin with the artist Stanislav Tanichev, who illustrated his articles. Courtesy of RFE/RL Ivan Astashin and Vladimir Akimenkov, October 11, 2020, Moscow. Courtesy of

Ivan Astashin and Vladimir Akimenkov, October 11, 2020, Moscow. Courtesy of  “Russia’s political prisoners: the jailed will sprout up as bayonets.” A banner hung over Nevsky Prospect in Petersburg by the Pyotr Alexeyev Resistance Movement (DSPA) in August 2012. Photo courtesy of

“Russia’s political prisoners: the jailed will sprout up as bayonets.” A banner hung over Nevsky Prospect in Petersburg by the Pyotr Alexeyev Resistance Movement (DSPA) in August 2012. Photo courtesy of

Vladimir Akimenkov. Courtesy of his Facebook page

Vladimir Akimenkov. Courtesy of his Facebook page Sergei Mokhnatkin. Photo courtesy of Julia Lorenz

Sergei Mokhnatkin. Photo courtesy of Julia Lorenz Maximum Security Correctional Colony No. 21 in Iksa, Arkhangelsk Region. Photo by Andrei Krekov. Courtesy of Julia Lorenz

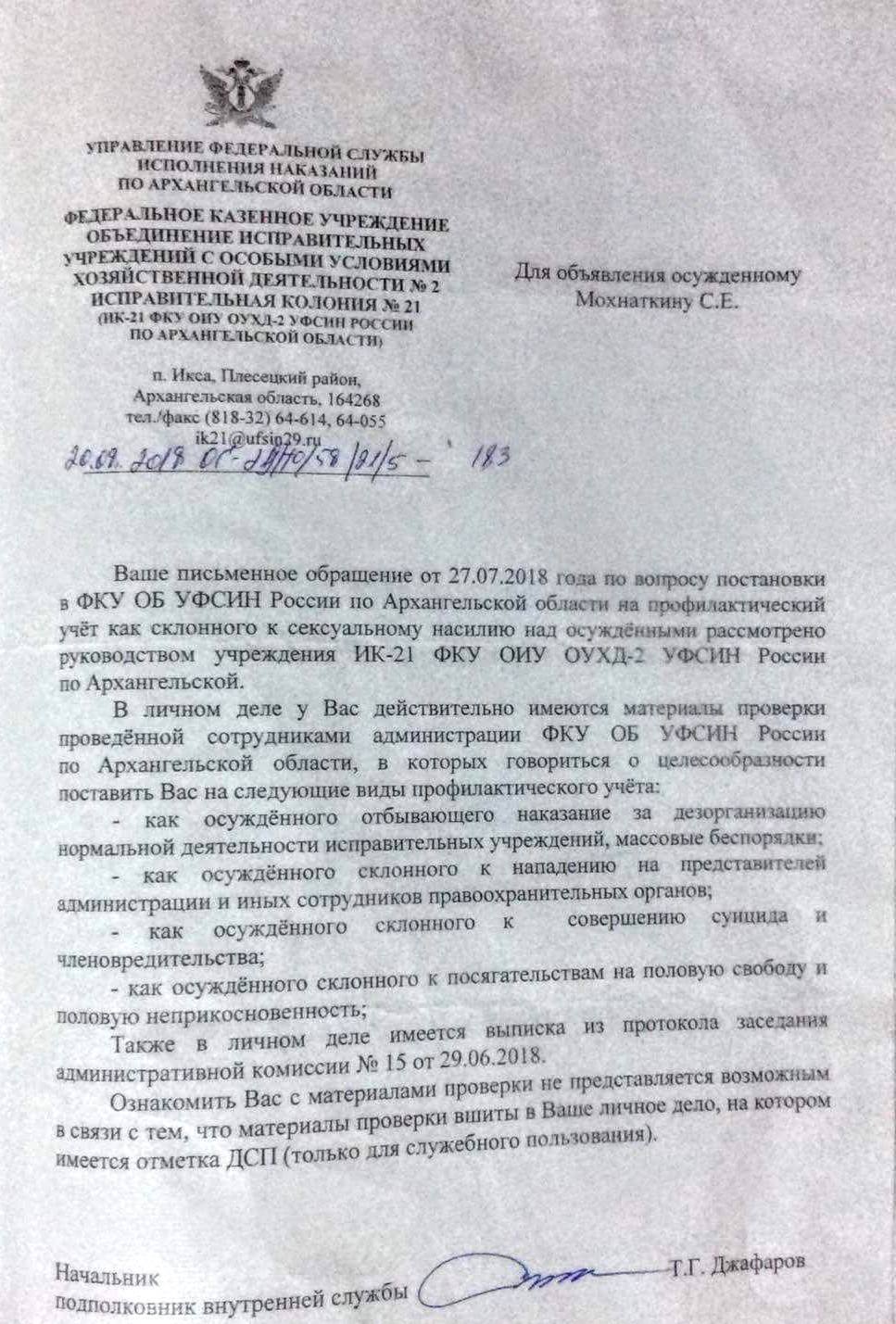

Maximum Security Correctional Colony No. 21 in Iksa, Arkhangelsk Region. Photo by Andrei Krekov. Courtesy of Julia Lorenz Letter from a prison official informing Sergei Mokhnatkin that he had been placed on “preventive watch.” Photo by Andrei Krekov. Courtesy of Julia Lorenz

Letter from a prison official informing Sergei Mokhnatkin that he had been placed on “preventive watch.” Photo by Andrei Krekov. Courtesy of Julia Lorenz Vladimir Akimenkov, raising money on behalf of Russian political prisoners. Photo courtesy of his Facebook page

Vladimir Akimenkov, raising money on behalf of Russian political prisoners. Photo courtesy of his Facebook page The room in the prison infirmary where Oleg Sentsov is kept.

The room in the prison infirmary where Oleg Sentsov is kept.