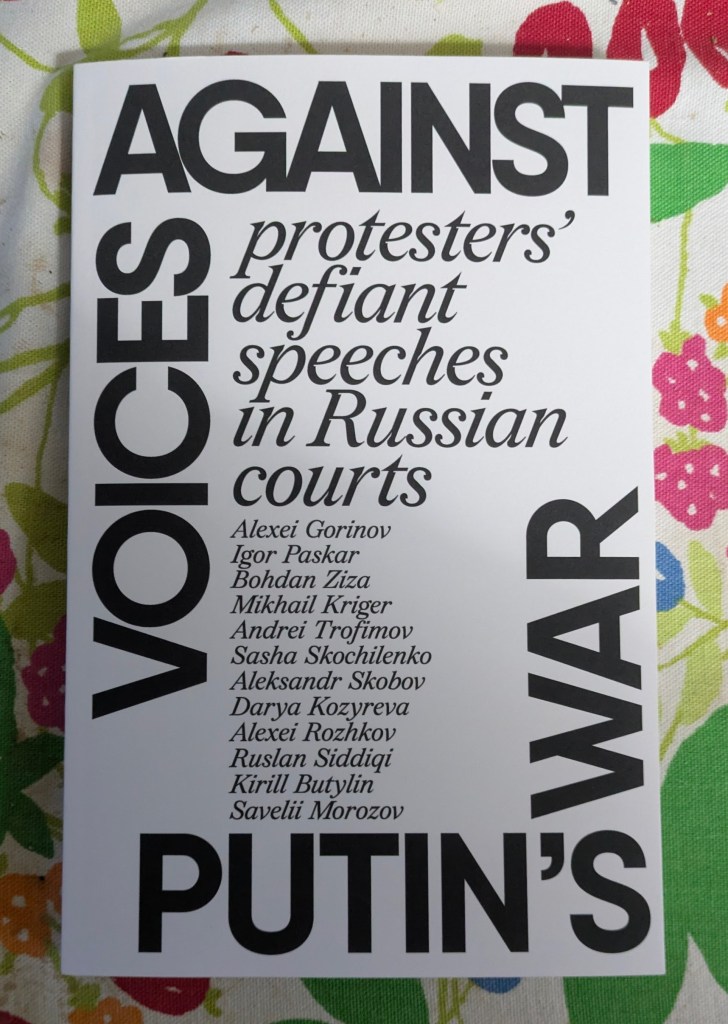

Thursday 20 November, 7:00 p.m. UK time: TRY ME FOR TREASON – Readings from anti-war protesters’ speeches in Russian courts, and book launch for Voices Against Putin’s War.

You are welcome to attend in person at Pelican House, 144 Cambridge Heath Road, London E1. Or watch the livestream here on Facebook, or on Youtube.

Source: Ukraine Information Group (Facebook), 18 November 2025

What can courtroom speeches by imprisoned protesters tell us about the breadth of anti-war resistance in Russia? British historian Simon Pirani discusses his new book Voices Against Putin’s War with independent Russian journalist Ivan Rechnoy.

Simon Pirani is a British researcher and author who has written about energy and ecology, the history of the Russian Revolution, the labor movement, and post-Soviet Russia. His recent book Voices Against Putin’s War: Protesters’ Defiant Speeches in Russian Courts compiles and analyzes the courtroom speeches of twelve prisoners who were sentenced for resisting Russian aggression in Ukraine.

— Today in Russia, hundreds of people are serving prison sentences for criticizing the invasion of Ukraine. Twelve of those people are the subjects of your book. How did you select them?

— We wanted to show that opposition to Putin’s war is widespread. What is striking about these people is their diversity. They come from different generations, have different life experiences, and hold different political views. This diversity demonstrates that, despite the absence of public demonstrations and the lack of any real possibility of organizing an open anti-war movement in Russia, an anti-war movement does exist there. It encompasses a very broad spectrum of Russian society as well as people from the occupied territories. For example, the book features the courtroom speech of Bohdan Ziza from Crimea.

We decided not to include some of the most well-known opponents of the war in the book — people who made brave and principled speeches in court, like Ilya Yashin, for example. Their statements had already been widely publicized in the media here. Instead our goal was to draw the attention of English-speaking readers to lesser-known figures.

On the one hand, there are those who simply said something or posted statements on social media. For example, Darya Kozyreva, the youngest person featured in the book, was arrested for laying flowers at the Taras Shevchenko monument in Saint Petersburg. On the other hand, these are those who did something, such as throwing firebombs — not with the intention of hurting anyone, but to draw attention to the injustice of the war. Igor Paskar and Alexei Rozhkov are among them. These are people who live in smaller towns far from Moscow or Saint Petersburg, where young men are much more likely to receive draft notices from the conscription service.

We also included the statement by Ruslan Siddiqi, who sabotaged a railway line to stop munitions from reaching Ukraine.

The texts for the book were put together by a group of friends who, since the February 2022 invasion, had been translating the courtroom statements and some of the posts from the media or social networks. When we were already well into that process, a lot of new material appeared on the website Poslednee Slovo [author’s note: the project’s name translates as “the final statement”]. It’s a terrific project that does an excellent job of collecting and publishing a much broader range of cases than we could cover.

We limited ourselves to people who have made explicit anti-war statements about the war in Ukraine. However, as you know, there are many other political prisoners who have appeared in court since the 2022 invasion, as well as many more from before that, especially among the Crimean Tatar political prisoners. They are all represented on the Poslednee Slovo website. Another remarkable thing about the website is that it goes back all the way to the Soviet period. They’ve included the 1966 speeches by Andrei Sinyavsky and Yulii Daniel, perhaps the first examples since Stalin’s time of people using the right for a final statement in court as a form of propaganda.

Our book includes a chapter that lists seventeen additional cases of people who delivered anti-war speeches, beyond the twelve protagonists whose complete statements we published. We hope that either I or my colleagues will eventually translate all of those speeches as well.

Unfortunately, the final courtroom speech has become something like a literary genre in its own right. This tells us a lot about the difficult and fearful times we are living through.

— How do you envision the audience for this book? Are they people in the West and elsewhere who already have some understanding of the situation in Russia and want to learn more? Or are they readers to whom you want to convey a political message — perhaps even to persuade them of something?

— The book is in English and is therefore intended for English-speaking readers rather than Russian-speaking readers. Only a small percentage of people in the UK, the US, and Europe can read Russian. Since 2022, many of us have been aware of the fate of the anti-war movement in Russia. As you know, it began with large demonstrations, but protesting soon became difficult and then almost impossible. Next came the firebomb attacks on military recruitment centers — actions not meant to harm people, but to draw attention to the anti-war cause. We then started reading, in Russia’s opposition media, the final statements of opposition figures — the courtroom having become, in effect, the last public forum in Russia where protest is still possible.

However, I think that many people in English-speaking countries remain unaware of all this.

So, to answer your question, our aim is to reach a wider audience in Western societies: not only those who have closely followed Russia’s attack on Ukraine and its consequences, but also those whose understanding of it comes only from what they have picked up incidentally through the media.

— One of the central figures in your book is Alexander Skobov. One might say he bridges two eras. He was a dissident in the Soviet Union and is once again among the persecuted today. There is another similar example that is not included in the book: Boris Kagarlitsky. How do people in the West perceive the difference between current repressions and the dissident movement during the Cold War? Also, how do they see the difference between the Russian and Western situations now?

— First, I would like to say a few words about Skobov. As someone who regularly travelled to Russia between 1990 and 2019, I was deeply affected by these courtroom speeches. The first one I came across was by Igor Paskar. I thought, “My God, these are such young people — not the youngest, but still much younger than me — who have entered this fight.” Alexander Skobov’s speech also affected me emotionally, perhaps because he is about my age — a year or two younger — and, as you said, he bridges two eras.

I was particularly touched by the letter that he wrote to his partner, Olga Shcheglova. It was published in Novaya Gazeta Europe, and we also included it in the book. In the letter, Skobov explains that some of his friends and comrades urged him to leave Russia, but he refused. This made it inevitable that he would eventually face trial and imprisonment. In the letter, he explains that he wanted to communicate to the younger generation that the small group of dissidents he once belonged to — the socialist wing of the Soviet dissident movement — stands in solidarity with them in these difficult times. He wanted this message to be recorded in history.

I think that is a very important statement, and we all owe Alexander Skobov gratitude for linking these two historical periods through his sacrifice. I hope that including his statements in our book will help people in the West understand this continuity more clearly.

I will try to answer your question about how these movements are perceived. During the Soviet era, people in the West generally considered the dissident movement to be very small and marginal. Given how communication worked back then, it was very difficult for information to break through. Of course, there were large revolts against Soviet power, beginning with the Novocherkassk uprising in the 1960s and other violent revolts in the 1970s and 1980s. I have a friend in Ukraine who studied the major revolt that took place in Dniprodzerzhynsk. These movements were very short-lived, and we hardly knew about them in the West, even those of us who were interested in what was going on in the Soviet Union.

Today, Russians — and Ukrainians, of course — have a much greater opportunity to have real conversations with people in Western Europe. I think the powers of that time really succeeded in dividing Europe; there really was an iron curtain. But that’s gone now. Millions of Ukrainians and Russians live in Western Europe, the UK, and the US. People are learning to communicate with each other and work together in new ways.

We can already see examples of this in Germany, in the UK, and elsewhere. I think this conversation must continue — and our book, I think, is part of that ongoing dialogue.

Of course, it’s not easy to communicate with someone who is literally in a Russian prison. However, through the friends, comrades, and families of the central figures in our book, I hope this conversation will begin and continue over a long period of time.

— I wanted to ask specifically about the possibility of connecting the Russian-Ukrainian and Israeli-Palestinian agendas. We are, of course, impressed by the huge mobilization in support of Palestine. At the same time, many on the left are frustrated that active support for Ukraine — a country in a situation in some ways similar to that of Palestine — is far less widespread in Europe and the West. Have there been any positive developments in this regard recently?

— Since October 2023, we have all watched with horror as Israel’s assault on Gaza has unfolded. It has been widely recognized as a genocide, and we now see a larger and more enduring anti-war movement in Western countries than we have seen in decades — comparable perhaps only to the protests against the US-UK invasion of Iraq in 2003, or even the movement against the Vietnam War in the 1970s.

One of the reasons I felt it was important to translate these texts into English was to show Western audiences how much the Russian anti-war movement has in common with movements here. Of course, their enemies are different, standing on opposite sides of the geopolitical divide, and there are many other differences as well. Yet the similarities are striking — and deeply significant. The motivations of some of those who gave these courtroom speeches — whose statements we have translated — are very similar to those of activists in the UK who have been arrested for supporting Palestine Action, or of those who joined the flotilla recently stopped by Israeli forces as it attempted to reach Gaza.

I spent much of last year attending the large British demonstrations against Israel’s assault on Gaza and calling for a ceasefire. Together with friends, we carried a banner stating: “From Ukraine to Palestine, occupation is a crime.” Our group wanted to show our fellow demonstrators that Ukraine’s struggle for national self-determination and the Palestinians’ struggle for freedom from Israeli occupation share something essential — the right to decide their futures, free from foreign interference and military threats.

We received a very interesting response from other marchers. Those familiar with the politics of the so-called left and socialist movements will recognize the reaction we encountered from a small minority, mostly older people, who said things like: “Why are you siding with Ukraine? Ukraine is just a plaything of the Western powers, a puppet of NATO. Why even talk about this issue?” Yet the overwhelming majority — more than ninety percent — of those who approached us said, “Ah, yes, we hadn’t thought about it that way before, but there really is something in common between these struggles.”

Another major obstacle to unity comes not only from the “campism” of certain leftists — those who focus exclusively on American and British imperialism while downplaying or excusing Russian imperialism — but also from the state, the mainstream press, and government propaganda. The official narrative is consistently supportive of Ukraine and entirely condemnatory of Palestinian resistance. Ordinary people sense this imbalance — the racism and discrimination directed at the Palestinian cause, alongside the establishment’s favoritism toward Ukraine. There is some truth in that: the propaganda machinery of our ruling class here is largely sympathetic to Ukraine. Working-class people in the UK and across Europe notice this and grow suspicious. However, I believe that is a suspicion we can overcome — and that has been our experience.

All of this is my personal opinion. The purpose of the book, however, is to bring to English-speaking readers the voices of our friends and comrades in Russia — those brave people who have found themselves in court and who, in some cases at the risk of additional years in prison, have chosen to exercise their constitutional right (though not always respected by judges) to deliver a final statement before the court. It is a remarkably courageous and difficult decision.

— I wanted to thank you for the book, and I also wanted to ask you, since you have been interested in this topic for a long time: how did your interest in it arise, and why has Russia become so important to you?

— My connection with Russia began through the labour movement. I first went to Russia in 1990 — to Prokopyevsk, in western Siberia, where the miners’ strikes of 1989 had first broken out. At that time, I was working as a journalist for the mineworkers’ trade union here in the UK. We saw an opportunity to develop links of solidarity between Soviet miners and British miners. And we had some success. Our friends in the British miners’ union established a very close relationship with the Independent Miners’ Union of Western Donbas, based in Pavlograd. This friendship continues even today.

In those days, I was a member of a Trotskyist organisation, and in August 1990, we organised a meeting in Moscow to mark the 40th anniversary of Trotsky’s assassination. This, too, was part of a conversation between Western socialists and people in Russia and Ukraine that had been practically impossible during the “Cold War.”

I continued to follow what’s going on in Russia and Ukraine, and to write about it, and between 2007 and 2021, I worked at a research institute, writing about the energy sectors of those countries.

Since the pandemic, I haven’t been back to Russia. On February 24th, 2022, when the invasion began, I was at home and was shocked. We were all shocked. The invasion has changed everything, both in Ukraine and Russia, for many years to come. Together with friends, we began translating these courtroom speeches and posting them online. Gradually, that work grew into the idea of making a book.

I hope your readers will read it. Later this year, we’re going to make the book freely available as a PDF, so that everyone can access it.

If we do make any money — and I should say it is a very cheap book — all proceeds will go to Memorial and political prisoners. Nobody is making a profit from this project. The whole point is to share these voices with a much wider audience.

Sale! £15.00 £12.00

VOICES AGAINST PUTIN’S WAR

Protesters’ defiant speeches in Russian courts

Speeches by Alexei Gorinov, Igor Paskar, Bohdan Ziza, Mikhail Kriger, Andrei Trofimov, Sasha Skochilenko, Aleksandr Skobov, Darya Kozyreva, Alexei Rozhkov, Ruslan Siddiqi, Kirill Butylin and Savelii Morozov.

Foreword by John McDonnell, Member of UK Parliament

Edited by Simon Pirani

ISBN: 978-1-872242-45-3 (paperback)

e-ISBN: 978-1-872242-47-7 (e-book)

RRP: £15 (pbk)

e-RRP: £7 (Ebook)

196 pages; 140x216mm.

Publication date: September 2025

The E-book can be purchased at the usual online retailers

Any profits will be donated to Memorial: Support for Political Prisoners https://memohrc.org/en

Source: Resistance Books