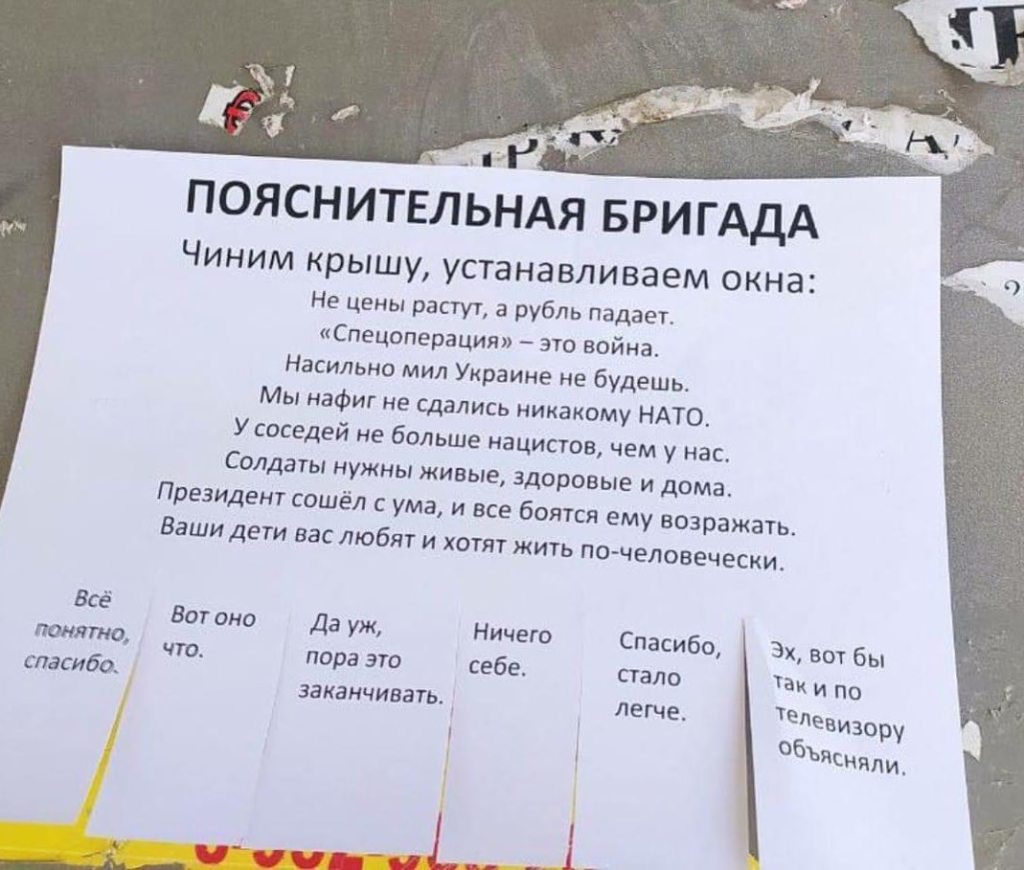

EXPLANATORY TEAM

Fixing the roof, installing windows:

It’s not the prices that are rising — it’s the ruble that is falling.

The “special operation” is a war.

You can’t force Ukraine to like you.

We haven’t surrendered to NATO.

The neighbors have no more Nazis than we do.

Soldiers should be alive, healthy, and at home.

The president has gone mad, and everyone is afraid to contradict him.

Your children love you and want to live like human beings.

That’s it, thank you.

So that’s how it is.

Yeah, it’s time to end it.

Wow.

Thanks, I feel relieved.

Oh, would that they would explain it that way on TV.

Source: Oleg Berezovsky (Facebook), 26 February 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader. Thanks to Nikolai Boyarshinov for the heads-up.

The war has made us take a look around. In whose midst do we live? Do our fellow citizens think the same way we do? Public Sociology Lab (PS Lab) is a research team that studies politics and society in Russia. In 2022, it launched a project to study the attitudes of Russians to the war.

How do people explain the conflict’s causes to themselves? How does their attitude to politics affect their personal interactions and self-perception? Do they have a political position at all? We talked about this with researchers at PS Lab. Svetlana Erpyleva works at the Center for Eastern European Studies at the University of Bremen, while Maxim Alyukov, a political sociologist, works at the Institute for Russian Studies at King’s College London.

How is your research on the attitude of Russians to the war with Ukraine set up?

Svetlana Erpyleva: Qualitative methods are the main difference between our team and the other teams doing systematic research on perceptions of the war. We have long conversations with our informants and try to find out not only their attitude to the war directly, but also many other things related to it — what sources of information they trust, how they interact with loved ones, their fears and hopes, and so on.

We searched for respondents using social networks, ads, and the “snowball” method (that is, when an informant helps us set up a conversation with their ow friends). It was a big help in contacting people who do not often reflect on politics.

Some people responded enthusiastically to the ads we placed about finding informants — they wanted to talk to us themselves. Moreover, these are not only people who have a clear stance for or against the war and are willing to share it, but also those who feel that their opinion is not represented in public discussion. Such people do not see other people who think like them on social networks or in the media and want to put themselves on the map.

For example, during the the second stage of our research, in the autumn of 2022, we realized that dividing people into “supporters of the war,” “opponents,” and “doubters” (as we had done in the spring) was no longer warranted. Our sources support some decisions by the authorities, but not others. They regard the war as necessary in some ways, but some things about it terrify them, while other things cause them to doubt. Our interviews, which last about an hour (sometimes longer), have in fact enabled us to understand the peculiarities of how the war is regarded by Russians, with all their contradictions and complications.

Our other goal is to study the dynamics of how the war is regarded. We conducted the first series of interviews in the spring of 2022. We did the second series between October and December 2022. It is important to note here that in the autumn we spoke only with “non-opponents of the war,” that is, with those whom in the spring we had provisionally labeled “supporters” and “doubters.”

Maxim Alyukov: I would also make another important clarification. When people talk about studying perceptions of the war, they often have in mind representative surveys. Using them, we can indeed more or less accurately describe the range of opinions around the country. But polls cannot show how opinions about the war are shaped, or what emotions people experience. We are going deep rather than wide. Yes, we cannot draw large-scale conclusions about public opinion in general, but, unlike the polling projects, it is easier for us to talk about specific mechanisms — what emotions tend to shape certain positions, how different types of media consumption affect perceptions of the war, and so on.

What is the difference between how people regarded the war in the spring and the autumn?

SE: On the one hand, we see from the autumn interviews that perceptions of the war had not changed radically. Almost none of the people with whom we had repeat conversations had changed their attitude to the war from “plus” to “minus” and vice versa. Of course, there have been small shifts in this regard. For example, some of the springtime convinced supporters remained “optimists,” while others had become “pessimists.” The former believe that the “special operation” is going in the right direction, despite all the shortcomings, while the latter criticize the chaos in the army, the chaos during the mobilization, retreats by Russian troops, and so on.

But we shouldn’t deceive ourselves: the pessimists have not stopped supporting the war. Rather, they want Russia to act tougher and more effectively, and ultimately win.

In the first series of interviews in the spring, we identified a group of so-called doubters. But it is clear that even back then different informants in this group were closer to one or the other pole of opinion. Some doubted, but were inclined to support the war, while others were against it. In the autumn, there were fewer informants who were completely unsure of their position. Those who had been closer to the supporters of the war had often begun to support the war a little more. The same thing happened to those who had been more against the war than not: many of them had become a little more strongly opposed to the war (without turning into unambiguous opponents).

On the other hand, the ways people have for justifying the war have changed. Some of the old methods are losing popularity, while others are emerging.

For example, one of the new justifications for war involves imagining it as a natural disaster. We feel sorry, of course, for those who perish in a flood. We cannot regard this other than negatively. But it is impossible for us to oppose it. The same thing has happened with the war.

From the viewpoint of the informants who have resorted to this excuse, the war just happened. It is a terrible reality that we can only accept.

Another new way of rationalizing the war involves turning its consequences into its alleged causes, as when our informants say, “Ukraine has been bombing our border cities, so we need to continue the war,” or, “The war has shown that we are fighting not with Ukraine, but with the collective West. We are fighting not with a fraternal people, but with our perennial enemy, so it is right that we started this war.” The second statement had also come up in the spring, but it has become much more popular. The rationale behind such justifications involves arguing that events that happened after the war started seemingly reveal the enemy’s true identity.

MA: Attitudes towards sources of information have also changed. There are two trends: polarization and stabilization. At the war’s outset, people tried to seek out information, including information from the “opposite camp.” For example, those who supported the war sometimes read opposition and Ukrainian media, because they understood that the Russian state media are propagandistic. Now, on the contrary, many people are so weary that they have not only reduced their consumption of information in general, but also have stopped following sources that reflect the opposite opinion.

At the beginning of the war, the following idea was often discussed: information about the destruction, civilian casualties, and losses among Russian soldiers would gradually undermine the effect of propaganda. Now we see that, over time, the simultaneous consumption of information from pro-government and opposition sources, which paint radically different pictures of the world, has had the opposite effect. It causes discomfort, which leads to the fact that people who are less involved try to shield themselves from information about the war in general, while more involved people consume propaganda and stop paying attention to alternative sources. This is a conscious choice: they realize that they are consuming propaganda. I remember the words of one informant: “There are different points of view, but the brain tends to stick to one theory. I’m inclined to choose the theory of my country, of the state media, so that my brain follows it.”

It transpires that the person understands perfectly well that they are consuming propaganda, and they consciously choose it amidst conflicting explanations that cause discomfort.

Do these changes produce any practical actions? Maybe people stop talking to certain people or get involved in charity?

SE: There are only a few volunteers among our informants.

People can have a positive view of charity, and worry about their country, but most of them do not take any action themselves.

And yet, volunteering that involves assistance to the mobilized is certainly seen positively by our informants (that is, by “non-opponents” with very different views of the war). Such volunteering is regarded not as involvement in the war, but as support for “our boys,” for “our country.” This is not surprising: there are always significantly fewer “activists” and volunteers than there are sympathizers. Only a few people are involved in protests, too.

Changes have also been taking place in the way people talk about the war with their loved ones. For example, many of our informants described the summer as a carefree time when the war had completely disappeared from their lives: they stopped discussing it. The mobilization was the “new February 24” for those informants (who were most often people remote from politics). The topic of war had returned to everyday conversations again. The informants were discussing the events even with strangers. For example, one of our sources told us that even at work meetings with her clients she had occasion to discuss the mobilization.

Do attitudes to specific events affect everyday practices? For example, the mobilization began and people decided to check whether their foreign travel passports were still valid.

SE: Unfortunately, we didn’t talk much about everyday practices in our interviews. Probably the most common reaction to the mobilization’s announcement was anxiety and, simultaneously, the absence of concrete action: “Whatever will be will be, but I hope that nothing bad happens.” Some of our informants who did not want to be sent to the front changed their places of work and residence, but we didn’t often encounter such people in our interviews. (It is important to understand that we were talking to “non-opponents” of the war.)

MA: It’s also worth recalling that a minority of Russians have the possibility of leaving the country. According to our research on social networks (this is another project that my colleagues and I are doing), the most common reaction to the mobilization has been evasion.

Is it possible, then, to talk about a desire for inner emigration among those who have remained in Russia? For example, a person says, “Actually, I have a lot more important and valuable things in my life [than the war], and I want to pursue them.”

SE: It was the presence of this desire among people in the spring of 2022 that made us single out the doubters as a separate group. All of them were typified by the notion that the “distant war” was secondary compared to more important values — work, loved ones, and family. But in the autumn, we saw that fewer and fewer of our informants were able to take a neutral stance, to completely distance themselves from assessing the war. Our informants talked about pressure: they seemed to feel that society demanded that they voice their opinion. In this sense, as Maxim has said, the polarization of views has been increasing.

But our informants assess [this polarization] in different ways. Many supporters of the war say that it is awesome because people are becoming more united, more interested in what is happening around them. The “anti-patriots” will leave the country, but patriotic Russians will remain. Others complain that it is hard for them to cope with the pressure. They would like to take a neutral position, but they cannot manage it. One of my sources described it this way (I’m quoting from memory, of course, but nearly verbatim): “I would like not to take a side, but my smart friends say that the war should be continued. And I understand that they are right, that one should support one’s country in such circumstances. I’m unable to take a back seat.” But a little later she said: “I’m afraid that time will pass and [people] will come and ask me, ‘Have you been reading Meduza? Have you been watching Channel One? Whose side are you on?’ And I won’t have any answer.” This situation even makes her think about emigrating. That is, on the one hand, she chooses to side with supporters of the war; on the other hand, she is afraid to make this choice.

MA: I would add that the desire for neutrality remains. One respondent put it this way: “There is war all round, but I try to maintain peace on my VKontakte page.” He moderates disputes there and shares links to articles about the importance of neutrality. For him, this is a way of creating a space for himself in which there is the possibility of remaining neutral, since he doesn’t have this possibility in other contexts. It is another matter that there are fewer and fewer opportunities for such neutrality.

You say that your respondents feel pressure. Where do they feel this pressure? In interactions with loved ones and colleagues, or somewhere else?

SE: It is often the pressure of their immediate environment. Many opponents of the war have left the country, and the doubters thus have fewer contacts with their viewpoint. They are surrounded, as a rule, more by supporters of the “special operation.” But the cause of such pressure may be an inner conflict. For example, our sources tell us that they were taught at school that when the country is in difficult straits, the worst stance is neutrality. But now they have found themselves in exactly this position. It is really difficult for them: they see the propaganda on both sides, but do not feel strong enough to resist it. This can be illustrated as follows: “Maybe Russia was right to attack, or maybe it was wrong to do so. Maybe Ukraine is the enemy, or maybe it isn’t the enemy. I don’t understand what’s going on at all. But how can I fail to take a stance?”

In such circumstances, people turn to what seems certain to them — for example, to their Russian identity. You may not know who is right, but you have a native country and it must be supported.

MA: This feeling of pressure consists of two parts. The first is personal interaction, about which we have said our piece. The second is the influence of the media, in which you can constantly see appeals and reminders of the war. This background encourages a person to clearly articulate their position.

Is the official newspeak (“special operation”, “line of contact,” etc.) incorporated into the explanations given by the “non-opponents” of the war? Is the state discourse generally used to justify it?

MA: Yes and no. It does happen that our sources literally quote propaganda narratives. For example, they start saying on TV that there are fakes everywhere, and a person repeats this idea. But at the same time, an absolute minority of our sources trust state broadcasts, although there are such people among them. They have doubts and come up with their own hypotheses. But it is important to take into account that our informants live in large cities, so it is likely that, for example, in smaller cities far from the capitals, the ratio is different, that there are fewer people there who are like the majority of our respondents, and more people who trust propaganda.

SE: You also have to understand that there are different types of support for the war, and therefore different explanations for it. There are people who accept the explanations given by the state media. Most often these people are elderly: they regularly watch TV, and then rehash the rhetoric of the propagandists. But there are other kinds of people — for example, those whom we call “committed supporters.” Their attitude to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict was shaped back in 2014, or even in 2004. They can be quite critical of propaganda narratives and are fond of saying, “We have bad propaganda. It is incapable of explaining anything.” Such people are able to explain the war’s causes on their own. And there are, for example, people who are remote from politics, who might watch TV sometimes, but it doesn’t convince them. They can even rehash propaganda cliches, but they do not adopt them, they do not present them as their own words. For example, they say, “We were told that…” or “We are told that…”

Is it possible then to say that, despite propaganda, polarization, and state pressure, even those who are not against the war are in a gray area? In other words, there are no views that could unite people, and accordingly, that is why they cannot unite and make demands.

SE: Yes, that’s right. Unless “convinced supporters” could try to create some kind of association. But I’m sure they’re a minority. Most people are busy with their daily affairs: they are not interested in political positions and movements. We are currently preparing a second analytical report on the results of the autumn stage of our study, and there we even try to avoid the word “position.”

Most of our informants have no “position.” Their attitude to the war is a bundle of fears, doubts, hopes, and other feelings. Such people may want Russia to win, but sincerely worry about the victims of the shelling in Ukraine.

One of our informants said, “If I had been subject to the mobilization I would have been out of Russia in three minutes.” And yet she, for example, wants Russia to win.

MA: Especially since propaganda does not just attempt to impose a certain point of view. It also generates a multitude of contradictory narratives that simply confuse people. This is a paradox of authoritarian propaganda: the state needs this vital demobilizing effect to maintain control, but it also prevents it from generating broad support for the war.

You mentioned sympathy for the victims of the shelling. In your spring report, some of your sources say that they would tolerate a decline in the material standard of living, because for them what matters are spiritual values. Since they are so clearly aware of losses, can we say that Russians perceive themselves as victims?

SE: We rarely see people regarding themselves as victims directly. They say, “The situation has become worse in Russia as a whole, but everything is fine with me. Yes, people are being mobilized, and that’s scary, but my loved ones aren’t being mobilized. Prices have gone up, but we’re coping.” Our sources often regard Russia as a whole as a victim. They are offended on Russia’s behalf: it was forced into the conflict, and it is humiliated everywhere and considered an aggressor. That is, they don’t think “[international] brands have abandoned me,” but those brands have abandoned “poor Russia.”

MA: Ukrainians are also regarded as victims. “The poor residents of Ukraine are being used by NATO. Would that it were over as soon as possible.” In many ways, this is part of the propaganda narrative that Ukraine has become a firing range on which NATO and Russia are fighting using Ukrainians as proxies. But this is, rather, a propaganda cliche that people simply repeat without thinking through their own position on this issue.

It follows that “non-opponents” of the war do not regard it as part of their personal lives?

SE: This is a generalization, of course, but I would say that it is basically true. For the opponents of the war, on the contrary, the war has become an existential challenge. Sometimes they even make themselves experience it as such: “I cannot live an ordinary life. I must remember that there is a war going on.”

But isn’t there a contradiction here? The “non-opponents” of the war do not regard it as a personal matter, but we are saying that they feel pressure from their loved ones, are trying to find their own identity, and are grasping for rationalizations.

SE: This is a difficult question, but let’s try thinking about it. Compared to opponents, supporters and doubters are more likely to try to rid themselves of negative thoughts, to distance themselves from the war. And yet it regularly makes its presence felt. The latter is a new trend, and many of [our respondents] do not like it: they would prefer to live their lives without being reminded about the war. But it has become more difficult to do this.

MA: In our research on how the war is seen by Russians, we have been observing what I had observed in my pre-war research. People, if they are not politicized, rarely hold consistent positions at all. I will give an example from my research on Russian perceptions of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine prior to February 24. A person has a smorgasbord of different political ideas. He supports all the decisions made by the authorities, including the annexation of Crimea and military backing for the so-called DPR and LPR. And yet half an hour later he says, “Basically, it would be a good idea to withdraw the troops and leave Ukraine alone. It’s bad for us.” It’s just that he hadn’t needed to make connections between his disparate views on this issue before. This necessity emerged during our conversation.

We have been observing the same thing now. People are trying to push the war out of their lives. They need arguments in favor of the war — not because it is their political position, but because it is safer to live that way. For many of our respondents, the interview was like an exam in which they were forced for the first time to think about logical chains and formulate at least some kind of a clear opinion about the war, which they had not tried to formulate before.

Source: Vitaly Nikitin, “‘One of the new justifications for the war involves imagining it as a natural disaster: we can only regard it negatively, but it’s impossible to oppose it’: what goes on in the minds of Russians who support the invasion of Ukraine?” Republic, 24 February 2023

What goes on in your mind? I think that I am falling down. What goes on in your mind? I think that I am upside down. Lady, be good, and do what you should, you know it'll work alright. Lady, be good, do what you should, you know it'll be alright. I'm goin' up, and I'm goin' down. I'm gonna fly from side to side. See the bells, up in the sky, Somebody's cut the string in two. Lady, be good, and do what you should, you know it'll work alright. Lady, be good, do what you should, you know it'll be alright. One minute one, one minute two. One minute up and one minute down. What goes on here in your mind? I think that I am falling down. Lady, be good, and do what you should, you know it'll work alright. Lady, be good, do what you should, you know it'll be alright.

Source: The Velvet Underground (YouTube), 10 August 2018

Throughout Putin’s war on Ukraine, the attitudes of the Russian public toward the regime and the conflict have been the subject of much scrutiny. This talk addresses this question by analyzing data released by the Presidential Administration that summarizes monthly correspondence received from the public from January 2021 through December 2022. While the identity of these correspondents is not known, their decision to send non-anonymous appeals to the President suggests that they support or tolerate the Putin regime. The data demonstrate that after an initial period of uncertainty about the war’s economic impact, these concerns abated until the announcement of mobilization in September. Since then, the appeals depict a Russian public that is increasingly concerned about conditions of military service and the war’s impact on service members and their families. At the same time, the data indicate that the Kremlin’s strategy to shift the blame for mobilization from the President to regional authorities appears successful.

Source: Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, George Washington University

Pollsters argue over how many Russians support the Ukraine war

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, sociologists have grappled with the question of how many Russians support the Russian army in Ukraine. Both independent and state-run pollsters claim they are the majority, and these studies are frequently referenced in Western media. However, at the same time, a group of independent sociologists have pointed out that these polls may not be representative — many Russians are reluctant to speak freely about their thoughts on the conflict due to draconian wartime censorship laws.

- Independent researchers from the Khroniki project recently presented the findings from their latest survey, which suggest using a percentage of how many Russians support the war may not be a very meaningful statistic. In their view, this figure comprises a misleadingly wide spectrum of people: from those who volunteered to fight in Ukraine to those afraid of repression. Moreover, at least half of those who are opposed to the war are afraid to speak out, the Khroniki sociologists said.

- To identify the core pro- and anti-war groups in Russia, the pollsters devised a series of questions. The results of their survey suggests that the core support group represents 22% of the population, while the core opposition is 20.1%.

- Separately, researchers stress that “the fridge counters the effects of the TV,” and this effect is felt more and more with each passing month. The level of support for the war among TV viewers who are encountering economic pressures is falling. Among TV viewers who have encountered at least one economic problem, support for the war was down 11 percentage points in February.

- Other polls, however, show that a vast majority of Russians support the war. For example, according to state-run pollster VTsIOM, 68% of Russian residents welcomed the invasion of Ukraine and just 20% are opposed to it. And leading independent polling agency Levada Center published results in January that suggested 75% of Russians support the war — to varying degrees.

Why the world should care:

It’s not easy to work out exactly what proportion of the Russian population supports the war, but Khroniki is certain that the pro-war lobby is far smaller than polls from leading agencies would suggest. If that is true, it casts doubt on the widely-held belief in the west that the war in Ukraine is supported by most Russians who remain inside the country.

Source: Alexandra Prokopenko, The Bell (Weekly Newsletter), 3 March 2023. Translated by Andy Potts

On 1 September 2022, I returned to Russia after almost a year away. The war that began six months ago had been present in my life daily: in the news, in conversations with friends and colleagues, and in the Ukrainian flags on the streets of the European city where I lived. But there was no trace of the war in the town near Moscow where I grew up, and where my parents still live. I did not see pro-war or anti-war graffiti or slogans; war was not mentioned in the streets or by my friends and acquaintances. As I sank into the familiar rhythm of my childhood town, I caught myself thinking that perhaps I was beginning to forget about it too. That all changed on September 21, the day ‘partial mobilisation’ was announced. Suddenly, the war was being mentioned all around me, or rather whispered about, in the cafe where I listened to Putin’s address, in the local library, in the street, on the train from Moscow to St. Petersburg. The war seemed to have reappeared in Russian society instantaneously, with the snap of a finger.

I had observed something similar before, not around me, but as a researcher: in the data my colleagues and I collected. Our Public Sociology Lab began conducting a qualitative study on Russians’ perceptions of the war on February 27, 2022, just three days after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. During the first months of the war, we conducted (link in Russian) over 200 interviews with supporters of the war, its opponents and doubters. At that moment, many of our informants, including those who were far from being exclusively anti-war, also said that they had been shocked by the news of the start of the ‘special military operation’ and had tried to make sense of events in their conversations with friends and relatives. But after a few weeks, the emotions of shock and confusion began to fade. The war became routine and faded into background noise.

So we knew that the ‘return of war to society’ following the announcement of mobilisation would also likely be temporary. We waited a few weeks and, on October 11th, conducted our first interview as part of the second stage of our research into Russians’ perceptions of war. Between October and December 2022, we conducted 88 interviews with ‘non-opponents’ of the war, deciding this time to focus the study on support for and disengagement from the war, rather than resistance to it. Forty of these interviews were repeated conversations with supporters of the war as well as its doubters doubters, with whom we had already spoken in the spring.

We were driven by the desire to understand how perceptions of, and predominantly support for, the war were evolving. From the interviews conducted in the spring of 2022, we roughly divided all ‘non-opponents’ of the war into supporters and doubters. Despite the fact that among supporters of the war, there were interviewees who were convinced to a greater or lesser extent, all of them found some means to justify the ‘special military operation’. Some were staunch supporters of ‘the Russian world’ and believed that the war would push the geopolitical threat away from Russia’s borders and strengthen the country’s position; some were worried about loved ones in Donbas and rejoiced at the prospect of an imminent resolution to the longstanding conflict; some, viewers of Russian TV channels, spoke of ‘combating fascism’ and ‘protecting the Russian-speaking population of Donbas’; many expressed confidence or, at the very least, hope: ‘if our government started the war, then it must have been necessary’. Although these people were worried about the casualties caused by the war and looked with apprehension at a future defined by isolation and sanctions, they remained supporters of the ‘special operation’.

It seemed to us, as it did to many others, that the announcement of mobilisation might fundamentally change something in the way Russians viewed the war. However, in addition to mobilisation, the war was marked by a series of other events, each of which could have left an impression on Russian society: the seizure of new territories and their subsequent annexation to Russia, the retreat of Russian troops, the bombing of the Crimean bridge, news of the bombing of Russian border regions. All this occurred against a backdrop of increasing Western sanctions, muddled explanations from the authorities as to why the country was at war, repression of dissenters, and increasing polarisation of views on the war in society. In such a state of affairs, we assumed that the views of the war held by ordinary Russians could not be sustained. In some ways, our assumptions were right, and in other ways, we were wrong.

It was not without reason that we waited a few weeks after the announcement of mobilisation and the swift ‘return of the war to society’ before we began the second stage of our research. The October interviews showed that the emotions associated with the announcement of mobilisation were as strong as they were fleeting. After a few weeks, they began to subside, and ‘partial mobilisation’ became normalised as a part of the new everyday reality. But, most interestingly, despite the negative attitudes towards mobilisation expressed by many of our informants who were not opposed to the war, their dissatisfaction with mobilisation rarely translated into dissatisfaction with the ‘special military operation’.

[…]

Source: Svetlana Erpyleva, “‘Once we’ve started, we can’t stop’: how Russians’ attitudes to the war in Ukraine are changing,” Re: Russia, 14 March 2023. Read the rest of this fascinating article (whose translator is uncredited, unfortunately) at the link. ||| TRR