Central Asian yardmen in Moscow taking a break from their work. Photo by and courtesy of Anatrrra

Central Asian yardmen in Moscow taking a break from their work. Photo by and courtesy of Anatrrra

‘People shout “Coronavirus!” at me as if it were my middle name’

Lenta.ru

March 29, 2020

The coronavirus pandemic has led to an increase in xenophobic attitudes towards people of Asian background around the world, even though the US has already overtaken China in the number of infected people, as have European countries, if you add up all the cases. However, according to an international survey of several thousand people, it is Russians who are most likely to avoid contact with people of Asian appearance, although one in five residents of Russia is not an ethnic Russian. Our compatriots of Asian appearance have been subjected to increasing attacks, harassment, and discrimination. Lenta.ru recorded their monologues.

“Being Asian now means being a plague rat”

Lisa, Buryat, 27 years old

Sometimes I am mistaken for a Korean, and this is the best option in Russia, when you are mistaken for Chinese, Koreans or Japanese. The disdainful attitude is better than when you are mistaken for a migrant worker from Central Asia, because the attitude towards them is clearly aggressive. At least it was before the coronavirus.

Now, basically, being Asian means being a plague rat.

A couple of days ago, a young woman approached me at work—I’m a university lecturer. The lecture was on fashion, and naturally I had talked about the epidemic’s consequences for the fashion industry. The young woman works in a Chanel boutique. She said right to my face that “only the Chinese have the coronavirus,” and she tries not wait on them at her store, but “everything’s cool” with Europeans.

My mother has to listen to more racist nonsense because she has a more pronounced Asian appearance than I do, because my father is Russian. For example, there are three women named Sveta at her work. Two are called by their last names, but she is called “the non-Russian Sveta,” although she has lived in Petersburg since the nineteen-seventies. And when I enrolled in school, the headmaster asked my father to translate what he said for my mother, although five minutes earlier my mother had been speaking Russian.

In the subway, she can be told that immigrants are not welcome here and asked to stand up. A couple of times, men approached her on the street and asked whether she wasn’t ashamed, as a Muslim woman, to wear tight jeans. She is learning English, and when she watches instructional videos, people in the subway, for example, say, “Oh, can these monkeys speak Russian at all? They’re learning English!” Police are constantly checking her papers to see whether she’s a Russian citizen. When I was little, we were even taken to a police station because the policemen decided she had abducted an ethnic Russian child—I had very light hair as a child.

Recently, she was traveling by train to Arkhangelsk, and children from two different cars came to look at her. At such moments, you feel like a monkey. (By the way, “monkey from a mountain village” is a common insult.)

Everyone used to be afraid of skinheads. Everyone in the noughties had a friend who had been attacked by skinheads. Everyone [in Buryatia] was afraid to send their children to study in Moscow. But being a Russian Asian, you could pretend to be a tourist: my Buryat friend, who knows Japanese, helped us a couple of times make groups of people who had decided we were migrant workers from Central Asia leave us alone. Another time, the son of my mother’s friend, who was studying at Moscow State University, was returning home late at night and ran into a crowd of skinheads. They asked where he was from, and when he said he was from Buryatia, one of them said, “I served in Buryatia! Buryats are our guys, they’re from Russia,” and they let him go.

Now all Asians are objects of fear. People shout “Coronavirus!” at me on the street as if it were my middle name. They get up and move away from me on public transport, and they give me wide berth in queues. A man in a store once asked me not to sneeze on him as soon as I walked in. I constantly hear about people getting beat up, and I’m very worried. My Buryat girlfriends, especially in Moscow, are afraid to travel alone in the evening. People also move away from them on transport and behave aggressively.

You can put it down to human ignorance, but you get tired of living like this. When you talk about everyday racism with someone, they say they worked with an Asian and everything was fine. This constant downplaying is even more annoying. You haven’t insulted Asians—wow, here’s your medal! It doesn’t mean there is no problem with grassroots racism in multi-ethnic Russia.

“When are you all going to die?!”

Zhansaya, Kazakh, 27 years old

On Sunday morning, my boyfriend, who is an ethnic Kazakh like me, and I got on a half-empty car on the subway. We sat down at the end of the car. At the next station, an elderly woman, who was around sixty-five, got on. When she saw us, she walked up to my boyfriend, abruptly poked him with her hand, and said through clenched teeth, “Why are you sitting down? Get up! We didn’t fight in the war for people like you.”

I am a pharmacist by education, and I have seven years of experience working in a pharmacy. The pharmacy is next to a Pyatyorochka discount grocery store. Recently, I was standing at the register when a woman of Slavic appearance, looking a little over fifty, came in. She came over with a smile that quickly faded from her face when she saw me. I only had time to say hello when suddenly she screamed, “When are you all going to die?! We are tired of you all! You all sit in Pyatyorochkas, stealing our money, and then act as if nothing has happened!”

I didn’t hold my tongue, replying abruptly, “Excuse me! Who do you mean by you all?” The woman was taken aback as if something had gone wrong. Then she said something about “CISniks” [people from the Commonwealth of Independent States], ran out of the pharmacy, and never came back.

I had always dreamed about driving a car since I was a kid. At the age of eighteen, I found a driving school, where I successfully passed the classroom training, and after three months of practice I had to pass exams at the traffic police. I got 100% on the written test the first time. But during the behind-the-wheel exam, the examiner began talking crap the minute I got into the car. When I introduced myself by first name, middle name, and last name, he said something I missed since I was nervous. Then he, a rather obese man, hit me on the thighs and screamed, “Do you want me to say that in Uzbek?”

I immediately unbuckled my seat belt and got out of the car. I gave up for good the idea of taking the driving test.

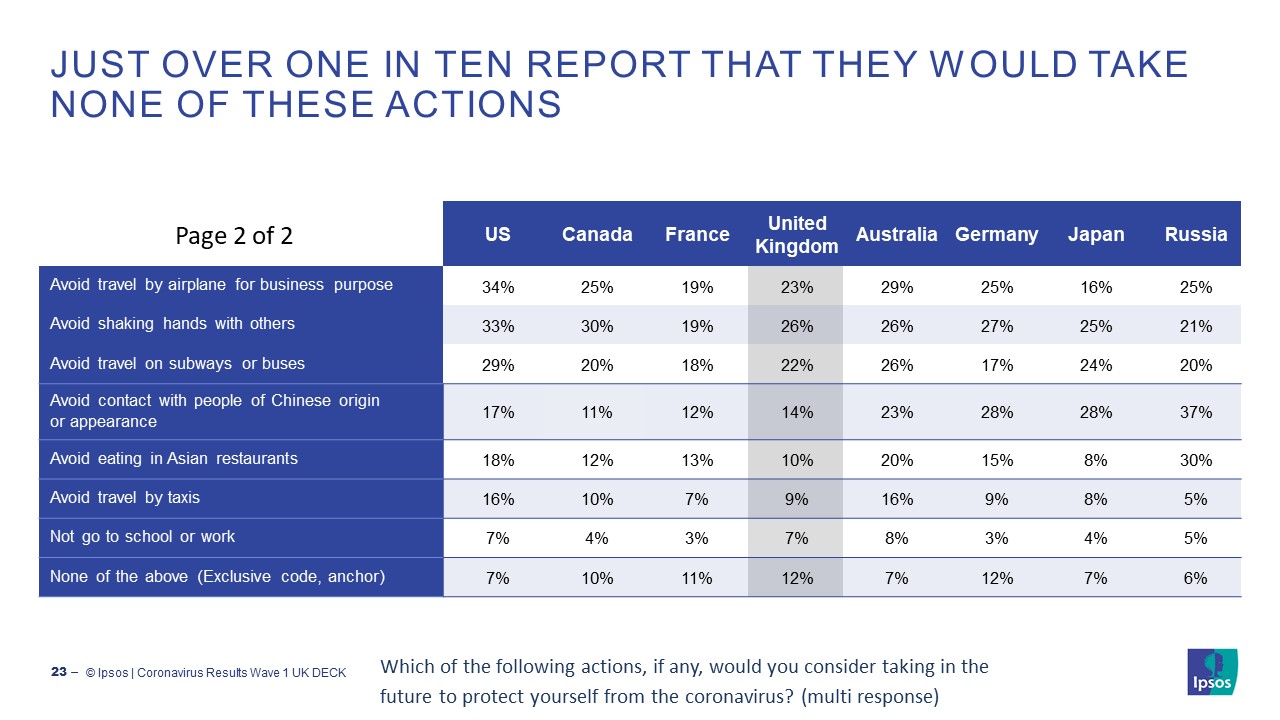

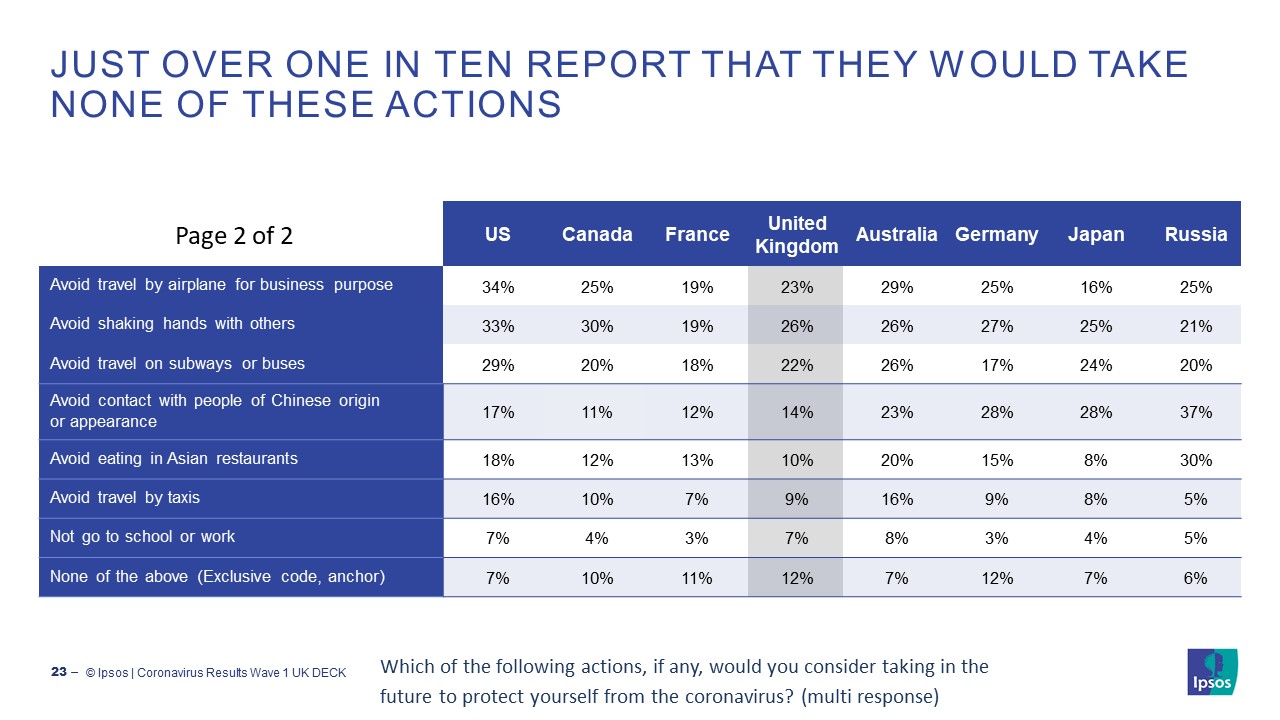

Results of an Ipsos MORI poll published on February 14, 2020

Results of an Ipsos MORI poll published on February 14, 2020

“The chinks piled into our country and brought this plague”

Anna, Buryat, 27 years old

We live in a multi-ethnic country that supposedly defeated fascism, but now every time I go into the subway, the police check my papers as if I were a terrorist. People really have begun to move away from me, give me a wide berth, and throw me contemptuous glances, as if to say “There goes the neighborhood!”

I live near University subway station [in Moscow], and there really are lots of Chinese students there. I feel quite sorry for them: they are constantly stopped by the police in the subway, and people look at them with disgust and demonstratively steer clear of them. If there are Chinese people who have stayed here, they probably didn’t go home for the Chinese New Year. Where would they bring the virus from? If they had gone home for the holidays, they would not have returned to Russia, since the border was already closed by the end of the holidays. Accordingly, the Chinese who are here are not carrying the virus.

Recently, I was going down an escalator. My nose was stuffy from the cold, and so I blew my noise softly. I thought I was going to be murdered right on the escalator: some people bolted straight away from me, while others shouted that I was spreading the contagion.

Recently, in a grocery store, a woman and her teenage daughter were standing behind me. The woman said something to the effect that all sorts of chinks have come to our country and brought the plague. She said it out loud and without any bashfulness, aiming her words at me. She and her daughter were less than a meter away from me, as if I didn’t understand them. My level of indignation was off the charts, but I didn’t say anything.

Another time, I went into my building and approached the elevator. A woman and her children literally recoiled and almost ran out—they didn’t want to ride in the elevator with me! I said I’d wait for the next one. They were not at all perplexed by the fact that I spoke Russian without an accent.

“I will always be second class here”

Malika, Uzbek, 21 years old

Recently, a mother and daughter passed by my house. Tajik yardmen were cleaning the yard. The girl asked the mother why she was rolling her eyes, and the mother explained that the yardmen were probably illegal aliens and terrorists. I walked next to them all the way to the bus stop—it was unpleasant.

During three years of living in Moscow, I very rarely felt like an outsider: the people around me were always sensible, and I was almost never stopped by police in the subway to check my papers. But when I decided to leave the student dorm, I realized that I would always be a second-class person here. It took four months to find an apartment. A girlfriend and I were looking for a two-room flat for the two of us for a reasonable amount of money, but every other ad had phrases like “only for Slavs.” There were jollier phrases like “white Europe” or “Asia need not apply.” But even in cases where there were no such restrictions, we would still be turned down when we went to look at flats.

After a while, I started saying on the phone that I was from Uzbekistan. Some people would hang up, while others would make up ridiculous excuses. In the end, we found a place through friends, but the process was quite unpleasant.

I’m no longer bothered by such everyday questions as “Why is your Russian so good?” I like talking about my own culture if the curiosity is not mean-spirited. But I am terribly disgusted to see how my countrymen are treated on the streets and realize that I’m left alone only because I’m a couple of shades lighter. Because of this, people take me for a Russian and complain about “those wogs” to my face.

“He shouted that I was a yakuza and had come here to kill people”

Vika, Korean, 22 years old

I’m an ethnic Korean. I was born and raised in North Ossetia, and graduated from high school in Rostov-on-Don. I have lived in Moscow since 2015, and I encounter more everyday racism here.

One day a woman on the street started yelling at me to get the hell out of Moscow and go back to my “homeland.” Another time, a madman in the subway sat down next to me and shouted that I was a yakuza and had come here to kill people.

When I was getting a new internal passport at My Documents, the woman clerk asked several times why I was getting a new passport and not applying for citizenship, although I had brought a Russian birth certificate and other papers.

Once my mother was attempting to rent an apartment for us and humiliated herself by persuading the landlords that Koreans were a very good and decent people. I wanted to cry when she said that.

There is a stereotype that Asians are quite smart and study hard, that they have complicated, unemotional parents, and so on. As a teenager, I tried to distance myself as much as possible from stereotypical ideas about Koreans. Now I can afford to listen to K-pop and not feel guilty about being stereotypical.

Generally, we are not beaten or humiliated much, but I don’t feel equal to the dominant ethnic group [i.e., ethnic Russians], especially now, when everyone is so excited about Korean pop culture, generalize everything they see in it to all Koreans and can come up to you out of the blue and say they love doramas. That happened to me once. It is very unpleasant—you feel like a pet of a fashionable breed.

In questionnaires on dating sites you can often find preferences based on ethnicity, and they can take the form of refusals to date people of a certain race, as well as the opposite, the desire to date such people. It is not a sign of tolerance, however, but the flip side of racism—fetishization. It still reduces a person to her ethnic group, suggesting she should be perceived not as an individual, but as a walking stereotype.

“Several times it ended in attempted rape”

Madina, from a mixed family (Tatar/Tajik/Kazakh/Russian), 25 years old

I was born in Moscow. My Russian teacher from the fifth grade on liked to repeat loudly to the entire class, “Can you imagine? Madina is the best Russian and literature student in my class!” By the end of the sixth grade, my classmates were sick and tired of this, but instead of boning up on Russian, they decided to throw me a blanket party. They got together, backed me into a corner, and kicked the hell out of me.

I recently returned from doing a master’s degree abroad and was looking for an apartment to rent in Moscow. Several times, landlords offered to rent an apartment without a contract, explaining that I undoubtedly needed a residence permit. When I showed them my internal passport and Moscow residence permit, they turned me down anyway.

Before moving to the United States, I had to forget about romantic relationships for several years because several times it all ended with attempted rape under the pretext “You’re an Asian woman, and I’ve always dreamed of fucking a woman like you in the ass.”

Nor was it strangers I’d met on Tinder who told me this, but guys from my circle of friends at school and university. There were three such incidents, and all of them combined racism, objectification, and a lack of understanding of the rules of consent.

“She looked at me like I was death, shoved me, and ran out of the car”

Aisulu, Kazakh, 22 years old

Recently, I was a little ill: I had a runny nose and sneezed once in a while. I wouldn’t even say it was the flu, just the common cold. I decided to attend lectures and put on a mask for decency’s sake.

I went into the subway, where people got up and moved away from me twice. I wasn’t particularly offended, but it was unpleasant when I stood next to a women after moving to another car and sneezed. She looked at like I was death, shoved me, and ran out of the car. That was quite odd.

I told a classmate about the incident, and she asked why I was wearing a mask, because it attracts more attention. I felt even worse, and took it off.

Translated by the Russian Reader

Central Asian yardmen in Moscow taking a break from their work. Photo by and courtesy of

Central Asian yardmen in Moscow taking a break from their work. Photo by and courtesy of  Results of an

Results of an  Opposition shaman Alexander Gabyshev was detained while walking to Moscow to exorcise Vladimir Putin. Photo courtesy of

Opposition shaman Alexander Gabyshev was detained while walking to Moscow to exorcise Vladimir Putin. Photo courtesy of