Ana Tavadze: We’re going in with a government that’s completely corrupt, a government that’s pro-Russian, clearly anti-Western, clearly does not really care about what the majority of the population wants and needs.

Ana Tavadze and Dachi Imedadze are members of the Shame Movement – a group with thousands of young followers working towards Georgia’s entry into the European Union.

Ana Tavadze: If Russia wins, it means loss of freedom, loss of everything that we fought for in the past 30 years basically. It’s a fight for values, it’s a fight for where you want to stand in this big fight for democracy.

Dachi Imedadze: As soon as the West in any form, be it the U.S. partnership, be it the European Union, is not represented in this country, Russia will fill the void right away.

They say the influx of Russians is already changing the face of Georgia.

Ana Tavadze: What are they doing, if we look at it? They’re buying apartments. They’re buying private property. They are opening up businesses. Their actions changed — Georgian economy.

Dachi Imedadze: The Russians are buying apartments here in every 33 minutes. They’re purchasing a piece of land in every 27 minutes. And they’re registering a business in every 26 minutes. So, I think we are on the brink of very dangerous situation here in Georgia.

According to public records, Russians have registered more than 20,000 businesses in Georgia over the last two years. And launched five new Russian-only schools, none of which are licensed by Georgia’s department of education.

Russians have driven rent up nearly 130%, prices for everything from food to cars have gone up 7%. over 100,000 Georgians have left the country because many of them can’t afford to live here anymore.

Sharyn Alfonsi: I’ve heard this described as a quiet invasion.

Dachi Imedadze: Quiet invasion, yeah. There is a risk of the economic diversions. There is a risk of military intervention. And there’s a risk of — Georgia’s statehood being destroyed.

Emmanuil Lisnif, George Smorgulenko and Pavel Bakhadov don’t look like much of a threat.

All Russians in their twenties, they fled their country for fear of being drafted or imprisoned for speaking out against Putin.

They now live in Georgia and work at this Russian-owned comedy club in Tbilisi.

Emmanuil Lisnif: I try and said ‘I’m against the war in Russia. I was beaten. and after that going to prison three times.’

Sharyn Alfonsi: So three times you went to jail?

Emmanuil Lisnif: Yes, yes three times.

Pavel Bakhadov: I believe and I know that Russians actually against the war.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You think that most Russians are against the war?

Emmanuil Lisnif: Yeah, just scared, really scared.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Have any of you had any aggression towards you because you’re Russian?

Pavel Bakhadov: Actually I have a big writing on the wall. It’s the biggest thing I see from my window, just big ‘Russians go home.’

There is no subtlety in spray paint… anti-Russian graffiti blankets the city along with support for Ukraine.

[…]

Source: Sharyn Alfonsi, “Denial of Georgia’s EU membership bid would be ‘a big victory for Russia,’ President Zourabichvili says,” 60 Minutes, updated 9 June 2024. The emphasis, above, is mine. ||| TRR

This text is based on interviews I did as part of the Hidden Opinions public opinion polling project, which I launched in 2022 and continued in 2023 and 2024. I spoke with dissenting Russians — with those who oppose the current regime and its military actions against Ukraine, both those who have stayed in Russia and those who have left the country. My youngest respondent at the time of the [first] survey was sixteen years old, while the oldest was seventy-two years old. These people hail from a wide range of professions and walks of life, but what they have in common is their categorical opposition to the actions of the Russian authorities. In just two years, I have interviewed 154 people for this project, some of whom I have spoken with two or three times.

In 2022, all of my respondents — both those who had left the country and those who stayed — espoused anti-war views and expressed a negative attitude toward the Kremlin’s policies. However, in 2023, about a year and a half after the war’s outbreak, a group amongst my sources in Russia emerged. Small at first, but constantly growing, it consisted of people who had changed their negative attitudes toward the war and/or the government.

This does not mean that such changes are impossible among those Russians who have left the country. Amidst a full-scale war, research based on representative samples is hampered by the fact that the most accessible respondents are those who have agreed to be interviewed as a result of self-selection. This is a significant limitation to the project.

My research is qualitative, not quantitative, meaning that it would be wrong to speak of a particular percentage of anti-war Russians who have become pro-war. I think it is important to study and understand how views are transformed and what triggers them to change. It is the subject of this text.

***

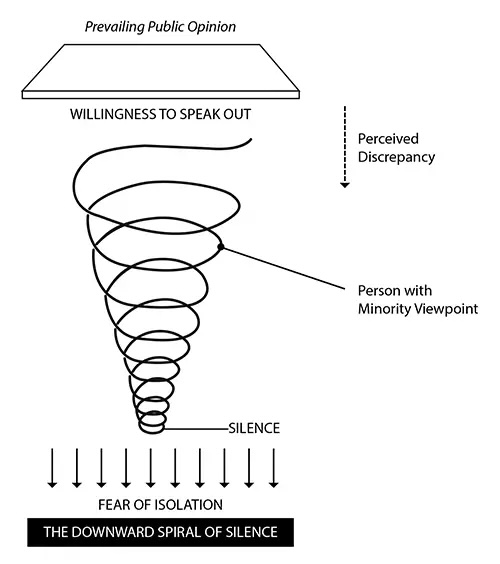

The sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman, experimenting with means of gauging the conservatism–to–radicalism spectrum, asked his students to do the following exercise. They were shown twenty drawings, the first one depicting a dog, the last one depicting a cat; in between, the dog gradually shed its canine features and turned into the cat. It was vital that the researcher record the moment when the test subjects had doubts about what exactly was depicted in the picture, when they realized that the dog had mutated irreversibly. In a sense, I have been doing something similar, trying to record the moment at which anti-war or anti-Putin views have been transformed into pro-war or pro-government views.

I have observed that such a change in views depends on a number of extrinsic factors, and the more such factors that are combined, the more likely it is that the person’s stance will change. In addition, a great deal is determined by an individual’s (psychological, social, etc.) resources. Finally, inconsistent views play an important role in transformation and adaptation. In recent years, sociologists have increasingly noted that people often pursue mutually exclusive goals simultaneously without noticing the contradictions in their own behavior.

New rationalizations, disillusionment and loneliness

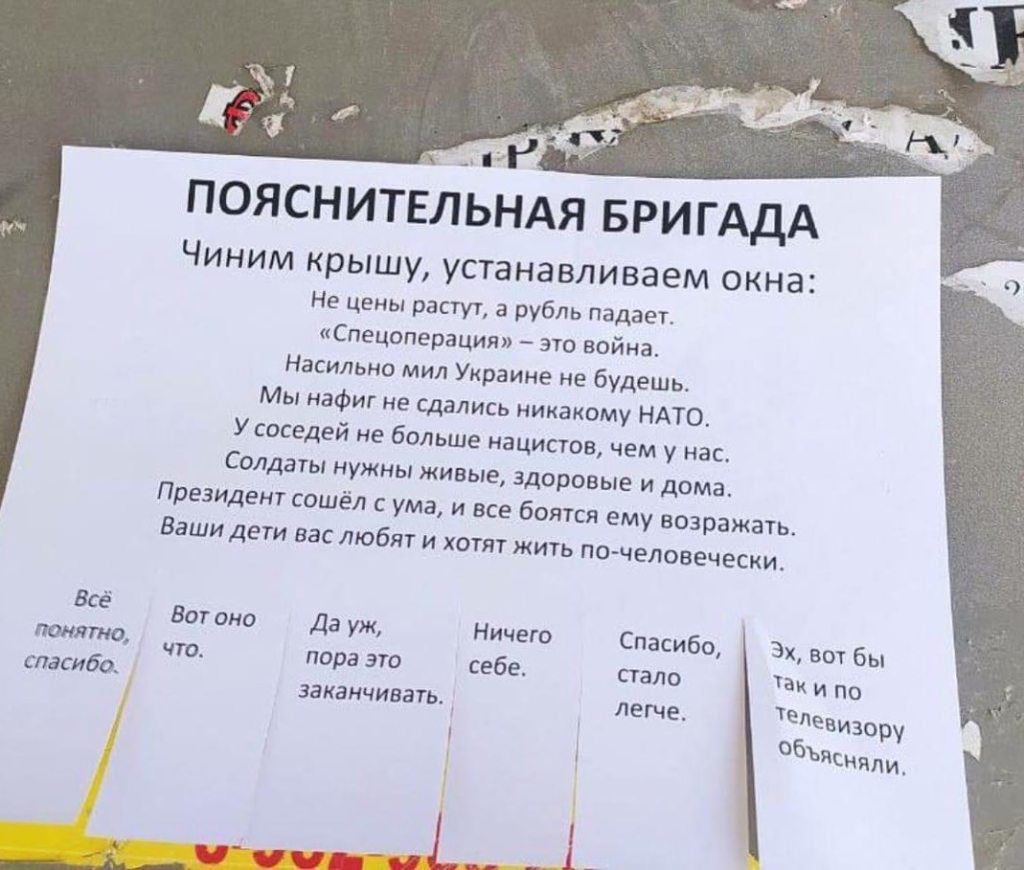

The gradual realization that the war is a long-term affair, combined with Alexei Navalny’s sudden death in a penal colony, has had a considerable impact on those resisting the regime within Russia. One can swim against the current, but it requires a considerable amount of strength, something not everyone possesses. It is difficult to be amongst the minority for years on end, to conceal one’s views and live in fear of being reported to the authorities. Respondents have thus begun reformatting [sic] their attitude to reality, explaining events in a new light and providing new rationalizations.

Failing to receive the expected support from the outside world or the possibility of a dignified workaround, some of my respondents eventually chose non-resistance to the regime, which in some cases has transmogrified into full-fledged loyalty.

“I don’t want to go to prison, I don’t want to play the rebel. I just want to live. If they send me to listen to ‘Exorcist TV,’ I’ll go without question. If they tell me to go to a [pro-war] concert, I’ll go. I’m not trying to convince anyone of anything anymore. I’m tired. I can only accept it and live the life I have.”

This stance is not directly bound up with support for the war or the regime. Rather, it indicates fatigue and the lack of strength to resist. If the circumstances shift in a direction more in keeping with their own values, these people will gladly slough off the “burden of adaptation.”

It is worth noting that, over the last year, many of my respondents have stopped following the news and focused on their daily lives. There are respondents who, despite the troubling times, have decided to have children. This is also a way of disconnecting from current events.

Another important factor influencing the change of respondents’ views is the narrowing of their circles of trust. Fearing denunciation, dissenters avoid making new contacts. Afraid of being alone and unwilling to live in fear, uncertainty and/or exile, they then join the majority.

The distance between Russians who have left Russia and those who have stayed in Russia has grown greater with every passing year. In 2022–2023, when I asked my respondents about opposition members who had left Russia, they most often would say nothing or would limit themselves to brief remarks along the lines of “We still watch them on YouTube, but they have less and less sense of what’s happening at home.”

Expressions of resentment and frustration have become more frequent in my interviews in 2024. My sources have said that the opposition often engages in wishful thinking and plays fast and loose with the facts, and that the west does not always act logically and decently.

Consequently, previously opposition-minded people have chosen to abandon painful and exhausting self-reflection in favor of loyalty to the regime. This helps them to get on with their lives, normalizing both the war and the political crackdowns. As one respondent put it, “Since the opposition and the west cannot be trusted, we will make friends with Putin. He is an ogre, but he is our own ogre.”

“Western countries seem to be doing everything to help Putin’s propaganda machine. I was quite surprised when I heard Angela Merkel say that all our negotiations were just a smokescreen: we wanted to let Ukraine catch its breath, and the negotiations were just a deception. That is, the leader of one of the largest countries in Europe openly says: a) we can’t be trusted in any negotiations, and b) we have conspired to deceive you. […] Putin’s propaganda machine skillfully makes use of this. But the point is not that the propaganda machine is using it, it’s that it is reality. As a normal person, a question occurs to me: if they treat us this way, [then] we are their enemies. After such statements, the ‘west’ is regarded as the enemy of Russians, and, accordingly, their enemy — Putin — is our friend.”

Those respondents who have changed their views on the war emphasize that when the west blocked their bank cards and accounts, when they heard what Ukrainians (including their relatives and friends) were saying about Russians and how they called for killing them, they decided that the current regime, whatever it was like, was less hostile to them on balance.

Tired of guilt, shame, disappointment and indignation, they have essentially chosen peace by joining the majority and accepting the existing rules: don’t discuss politics, don’t speak out publicly, swear to the values that the government declares. This choice seems reasonable to them in a situation in which no political activism is possible anyway, and the political crackdown machine is only picking up steam.

This strategy ensured material well-being and career success for some of my respondents. For example, some mid-level specialists in the IT sector received good positions and salaries, while for other people the involvement of their relatives in the war has been a means of social mobility and a source of access to material goods. Still others have benefited from the war by arranging parallel imports, etc.

Another factor contributing to the shift in sentiment from anti-Putin to pro-government has been the radicalization and polarization of society.

“A sharp delineation between ‘black and white’ leads to the opposite outcome. Any attempts to express doubts about the actions of the Ukrainian or western side are automatically regarded both inside and outside [Russia] as pro-Putin behavior, the outcome of brainwashing, etc. The other side appears infallible and beyond criticism.

“If you criticize the west’s actions in any way, you are automatically pigeonholed as a ‘Putinist.’ It makes me feel like saying: if that’s how you treat me, well, to hell with you, chalk me up as a Putin supporter.”

The state of rejection and isolation provokes protests amongst some people: since the west condemns them for staying in Russia, they “will go the full mile and become real orcs.”

The mechanisms by which feelings of rejection are transformed into collective pride have been described by researchers and are not unique to Russia. These feelings reinforce nationalist sentiments and contribute to the strengthening of authoritarian regimes.

Emotional dilemma

Speaking about the change in their views from anti-war to pro-war, my respondents noted that in one way or another they were surrounded by people who had suffered in the war: classmates or school friends who had been drafted to the front or had volunteered for combat, their children, colleagues, and mere acquaintances. Telling them straight to their face that their sacrifices were in vain had become both emotionally more difficult and more dangerous. To maintain relationships and friendships, my sources generally had to listen in silence to their acquaintances’ stories about what they had experienced and seen at the front. And if they were people who mattered to them, it was impossible not to sympathize with them.

We should understand that Russians who initially opposed the war and the regime but remained in Russia feel definitely closer to those who went to the front or delivered humanitarian aid there than to those who have left the country. They are “in the same boat” as their relatives, friends, and colleagues. They feel compassion for them.

“When we were teenagers, all sorts of things happened. If the guys were caught [by the authorities], I would perjure myself and lie in all sorts of ways. Later I could tell them what I actually thought of them, but I wouldn’t abandon them. That’s not the way that blokes do things. Now I realize with my head that they are wrong a hundred times over, but they are my boys, I am on their side. And even if I am against the war, I cannot be against them.”

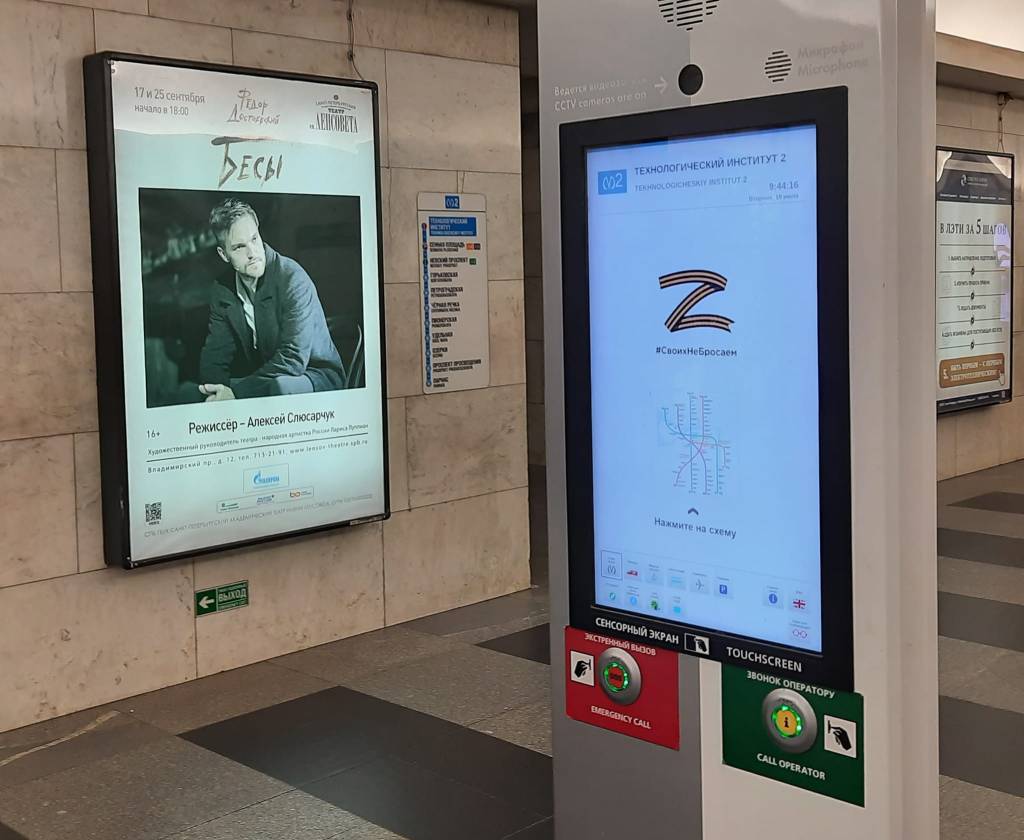

Propaganda equates anti-war sentiment with betrayal, and it paints people who espouse such views as accomplices of Russia’s enemies, who want to kill as many Russians as possible. This causes a very heavy feeling, my respondents note.

Meanwhile, the state softens such emotional blows by offering loyal citizens new benefits and additional material and social goods, free concerts, and beautiful and comfortable urban environments, demonstrating concern for people in general and for those returning from war in particular. “People-centeredness” has become the buzzword in the PR strategies of many employers and officials throughout Russia.

Russians who are concerned about their neighbors also respond to calls for help front-line soldiers, because amidst war and external isolation it is these people with whom, they say, they “share a common plight.” One of my respondents, overwhelmed by such sentimental feelings, volunteered for the army.

As a religious man, he hoped he would not face the need to kill others, but would be able to help “his boys” without bearing arms, because he “could not stand on the sidelines any longer.” If the need to kill arose, he would desert, my source had decided, explaining that he was emotionally prepared to be beaten up and go to prison.

Another type of people whom I have encountered more and more often are those whom researchers Maria Lipman and Michael Kimmage have characterized as anti-anti-war: these people do not necessarily support the war, but they strongly condemn or resent “unpatriotic” fellow citizens who do not support the Russian army or who even take the side of Ukraine.

Seeing soldiers returning from the front and watching the growing number of Russians killed in combat, my sources now often place the blame not on Putin or the Russian military, but on their compatriots who oppose continuing the war until Russia achieves total victory.

Ressentiment and the “demons” of propaganda

Propaganda has awakened ressentiment in some of my respondents. They have come to believe that this war is really about maintaining Russia’s status as a great power, which its enemies are trying to flout and rob. Such people believe it vital that Russia maintain its status as a victor, and they accept the state-imposed version of Russian history that asserts Russia’s greatness in all periods.

War, as happens under autocracies and dictatorships, is seen as the ultimate manifestation of the nation’s strength and vitality and a guarantee that its culture and traditions will be maintained. In conversations with me, my sources have repeatedly used the phrase “releasing demons,” referring to the fact that the current situation helps their acquaintances and themselves experience a sense of unity and superiority over the rest of the world, a sense of their own righteousness and chosenness.

Some respondents noted that the official rhetoric, concrete and catchy, seemed more acceptable to them than the verbose arguments and meaningless self-reflections of the opposition.

Meanwhile, according to my respondents, the number of anti-war-minded Russians today is decreasing. Since Navalny’s death, I have often heard in interviews that every second or third person in the orbit of my sources has changed their views.

It is difficult to say how strong this trend really is. I would estimate that a third of those who unequivocally opposed the war and the regime when I spoke to them [initially] have changed their views, but of course these numbers are in need of supplemental verification, which is not easy to accomplish today. There are probably also people who have switched their pro-war patriotic views to oppositional ones, but I assume that we hear the voices of these people even less frequently.

Respondents who are in a state of uncertainty and/or in the course of switching their views feel the need for support, at least informational support. They need arguments explaining that anti-war sentiments are not a betrayal and that the current war is destroying Russia, not restoring its greatness. But they also acknowledge that such an argument would hardly convince them under the current circumstances. For now, the only thing they think they can do is to maintain their sanity and adapt to reality in order to live to see better days.

***

The Russian regime has proven to be “smarter” and more adaptive than Russian opposition activists and western democracies thought, but this does not mean there is no point or possibility of supporting by any means possible those who have remained in Russia and are still resisting the regime or straddling the fence. One way or another, positive change in Russia is impossible without their involvement.

Source: Anna Kuleshova, “‘I’m a person with anti-war views, but I suddenly found myself signing up for the front’: how and why Russians have changed their attitude to the war,” Republic, 4 June 2024. The emphasis, above, is the author’s. Translated by the Russian Reader