Popular opinion polls show that the majority of Russians support the military action in Ukraine. Researchers, however, continue to argue that society’s support for the war is much lower than these figures suggest. In their new study “Perception of the conflict with Ukraine among Russians: testing the spiral of silence hypothesis,” V.B. Zvonovsky and A.V. Khodykin, drawing on Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann’s “spiral of silence” model, argue that many opponents of the war are not willing to voice their opinion, believing that it is unpopular and fearing social disapproval.

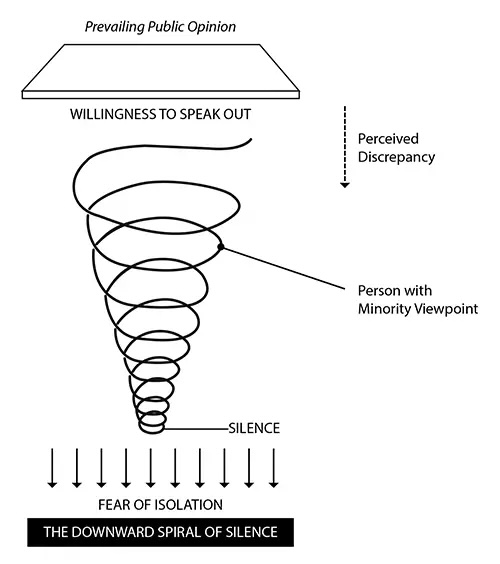

Noelle-Neumann argues that before people with a “limited interest in politics” decide to voice their opinion on a politically significant matter, they assess the risk of being condemned by others. The spiral of silence “twists” as follows: people who are afraid of being isolated due to the unpopularity of their opinion refrain from voicing it → this opinion is thus heard less and less often in society → people thus increasingly think that their own opinion is not popular → they are thus even less likely to be willing to voicing it.

Zvonovsky and Khodykin discovered that the spiral of silence actually does have a great impact on discussion of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict in Russian society. They were able to verify this by doing a nationwide telephone survey (N = 1977) using Noelle-Neumann’s “train test.” The “train test” measures the willingness of “adherents of a particular stance on a socially significant matter to openly voice it by discussing it on a train with a random fellow passenger.” Supporters of the more popular stance, in their opinion, are more likely to openly voice it, believing that they are “in a stronger camp and less at risk of being judged by others.” Sometimes, their opponents are also encouraged to side with the “stronger” position.

Applying the “train test” to the Russian context showed that the topic of the war is highly sensitive both to its supporters and opponents, and that the spiral of silence affects both sides of the discussion. However, its impact on opponents of the war has proved to be much stronger than on its supporters. Thus, people who oppose the special military operation in Ukraine are less willing to discuss the Russian-Ukrainian conflict with those who support it.

Another important finding made by the researchers is the fact that a person’s willingness to speak out about the war is influenced most by the distribution of opinions about it in their immediate circle of acquaintances. So, the more people in the orbit of respondents who had shared a similar opinion with them, the more the respondents were willing to discuss the war, and vice versa. It can be assumed that the need to maintain social ties is stronger for Russians than the need to defend and disseminate their political views, as we noted in our analytical report “The war near and far.” Zvonovsky and Khodykin suggest another explanation, however: the “bad experience” of political discussions, which often end in conflict and frustration, also has an impact, since the opinions of interlocutors are not changed, and the desire to talk about the war with one’s political opponents thus simply disappears.

The last interesting finding of the authors about which we want to tell you is the following. If the environment of the respondents is divided approximately equally (~50% “for” the war and ~50% “against”), then the probability that those oppose the special military operation will discuss it does not decrease—unlike supporters of the war, who are much less likely under the same circumstances to discuss the military operation with strangers of opposite views. Thus, the opponents of the military conflict “have learned to resist the spiral of silence better than their opponents.” This means that if the distribution of opinions in Russia changes, “opponents of the military conflict will have greater opportunities than [their] opponents to promote their own narrative about the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.”

Source: PS Lab (Telegraph), “The spiral of silence and the war in Ukraine: review of a new sociological study,” 14 December 2023. Translated by the Russian Reader. Image, above, courtesy of Businesstopia

IOWA CITY, Iowa — Anti-Donald Trump Republicans know they are in the middle of a critical moment to stop the former president’s political comeback. But for some, the steep cost of voicing resistance to Trump often renders them silent.

“If you go against Trump, like — you’re over,” said Kyle Clare, 20, a member of the University of Iowa’s College Republicans.

“I don’t talk about Donald Trump a lot because I’m afraid of the backlash,” said Jody Sears, 66, a registered Republican from Grimes, Iowa.

“If you would say something negative about Trump, we had one person that would just go bang for your throat,” said Barbra Spencer, 83, a former Trump voter describing her experience living in senior apartments in Spillville, Iowa.

Trump still enjoys broad popularity in the Republican Party, and that’s driving his polling leads among Republicans in Iowa, New Hampshire and every other state ahead of the 2024 primaries. But he has also used that popularity to enforce unity. And the same impulse that has led Republican officeholders to avoid criticizing Trump because of potential threats to their safety and their jobs is also holding back rank-and-file voters from opposing the former president in public with the full strength of their personal convictions.

NBC News spoke to more than a half-dozen Iowa voters turned off by Trump — but some were anxious about talking on the record out of fear of being shunned by friends or family. One Iowan said they plan on saying they caucused for Trump when asked by members of their community but will actually caucus for Vivek Ramaswamy.

That adds up to signs going unplaced on front lawns, conversations with friends and family about other candidates avoided — and fewer opportunities for opposition to Trump to take hold in different Republican communities.

NBC News first spoke with Clare in a University of Iowa auditorium Aug. 23, the night of the first GOP presidential debate. Fellow College Republicans were reacting to the debate and voicing steadfast support for the GOP candidate who wasn’t on the stage: Trump.

Clare chose to wait until the end of the night, after the rest of his classmates left the auditorium, to share his thoughts.

“I’m just so scared of doing this right now,” he said, fighting back tears. “I want to be able to have my opinions on our politicians, and I want to be able to speak freely about them and people still understand I’m a conservative.”

Clare criticized Trump, particularly for his actions Jan. 6, 2021, saying, “The end of his administration was un-American.” He also said Trump’s supporters are in denial about losing the 2020 election.

“They don’t want to believe he lost the election. It’s hard to swallow. Losing is hard to swallow. But it’s important that when we lose, we recognize that we lost and we think, ‘What can we do better next time to win over Americans?’” Clare said.

Clare was right to expect backlash from speaking out on Trump. After NBC News published the interview with him on a “Meet The Press” social media account, hateful and homophobic comments poured in. Clare said later that a student came up to him at a university event, shoved a phone in his face with the video on it, and asked him why he’s “scared of Trump and not scared of getting AIDS from having gay sex.”

“Say something they disagree with, and they go after your sexuality,” said Clare, who added that he doesn’t regret doing the interview with NBC News. Many of the comments questioned if Clare — who holds a leadership role at the University of Iowa’s College Republican organization, interned for a Republican on Capitol Hill, and is heavily involved in the Johnson County, Iowa, GOP — was truly a Republican.

“I think it shouldn’t be a bad thing for me to say I am conservative and that I think there are other options, and I don’t think that this person is good for our country,” Clare said. But he’s worried those opinions will stunt his own long-term political ambitions.

“If people as powerful and as prominent as members of Congress can be taken down because of their criticisms of one man, what’s stopping that from happening to me?” Clare noted, referring to the Republicans ousted from Congress after voting to impeach Trump.

Trump’s criticism forced several senators and House members into retirement or primary defeat during his first years in office. Later, of the 10 House Republicans who voted to bring impeachment charges against Trump following the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, four retired before facing voters in 2022 and another four lost their next primaries. Only two remain in the House.

In the Senate, three of the seven Republicans who voted to convict Trump have since retired or resigned, and Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah is retiring next year.

Romney recounted to biographer McKay Coppins that Republican members of Congress confided to him they wanted Trump impeached and convicted but would vote against the charges because they were worried about threats to their families.

Former Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming, one of the Republicans who lost a 2022 primary after voting to impeach Trump, detailed similar conversations in her new memoir.

Cheney wrote about one colleague that she “absolutely understood his fear” about what would happen if he voted to impeach Trump. But, she continued, “I also thought, ‘Perhaps you need to be in another job.’”

‘It was easier to be quiet about it’

Rank-and-file voters are less prominent and thus less likely to be harassed or threatened, but some of the same worries and experiences remain. Sears, the Republican from Grimes, Iowa, feels Trump doesn’t reflect her values. But that’s an opinion she kept to herself until recently, because of the fear of being cast off by family and friends.

“Family and people I work with are Trump supporters,” said Sears, describing her hesitancy to speak out about her beliefs.

“I think Trump supporters tried to coerce or bully people into also being Trump supporters. And so it was easier to be quiet about it,” she said.

Spencer, a retiree now living in a nursing home in Decorah, Iowa, says Trump supporters at her previous retirement community created a toxic environment that stopped her and her friends from voicing opinions.

“We were afraid of arguments,” she said. “When you live with that many old people, sometimes they have very strange but very firm thoughts and you better think the way they do,” she said, explaining her silence.

Clare, Sears and Spencer are not the only people who feel this way.

And as Cheney and Romney’s stories demonstrate, social ostracization isn’t limited to just voters who speak out against Trump. Former Rep. Denver Riggleman, a Republican who represented a slice of Virginia from 2019 to 2021, says his mother texted him, “I’m sorry you were ever elected,” after he came out against Trump.

“It was so soul-crushing to have a family member choose Donald Trump over you,” Riggleman continued. He said evangelical Trump supporters in his life saw Trump as being blessed by God. “I was going directly against religious beliefs. And that’s a losing battle.”

It’s now been almost six months since a member of Congress endorsed a non-Trump candidate in the 2024 GOP primary, according to NBC News’ endorsement tracking.

The trend has popped up elsewhere on the 2024 campaign trail, too. When Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds endorsed Ron DeSantis in November, the Florida governor mentioned in an interview with NBC News that he “had people come to me and say they endorsed [Trump] because of the threats and everything like that” during the campaign.

Trump quickly went after Reynolds after news of her DeSantis endorsement broke, posting on social media that it would “be the end of her political career.”

‘Vortex of controversy and vilification’

Charlie Sykes was a conservative radio show host in Wisconsin for more than 20 years before Trump burst onto the political scene. Sykes was skeptical and critical of Trump, eventually confronting him in a heated interview about insults Trump hurled at Texas Sen. Ted Cruz’s wife in 2016. But for Sykes, it began to become clear that there was no room anymore for anti-Trump conservatives on talk radio.

“The audience of conservative talk radio began to think that loyalty was required. They wanted conservative media to be a safe space for them,” Sykes said, describing how his role became untenable.

After leaving radio, Sykes didn’t let up on his Trump criticism, which he says got him booted from a think tank and led him to lose friends and become a self-described political orphan. He says his criticism was met with bullying — and he understands why people who don’t work in the public eye might be hesitant to voice their true feelings about Trump.

“I do understand why people in their normal lives don’t want to be caught up in this vortex of controversy and vilification — why they would step back from all of this,” Sykes said.

Another longtime Wisconsin Republican recently detailed one of the results of that pressure.

Former House Speaker Paul Ryan recently spoke on video at an event for Teneo, a global consulting firm where he serves as vice-chair. Ryan said the impulse to avoid getting on the wrong side of angry Trump supporters pushed former colleagues to vote against impeachment even though they wanted Trump gone — and now he thinks there are many who regret those votes.

“They figured, ‘I’m not gonna take this heat and I’m going to vote against this impeachment because he’s gone anyway,’” Ryan said. “But what’s happened is that he’s been resurrected.”

Source: Alex Tabet, “Trump’s secret weapon consolidating the GOP: fear,” NBC News, 15 December 2023

Discover more from The Russian Reader

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.