What can serve as the basis for new Russian post-war identity? What sort of patriotism can there be in a country which has lived through an aggressive war? Of what should the people of this country be proud? What should they associate themselves with? Republic Weekly presents a programmatic text by the sociologist Oleg Zhuravlev and the poet and activist Kirill Medvedev on how the so-called Russian nation came to 2022 and what its prospects are in 2025.

How can Russia get beyond being either an embryonic nation-state or a vestigial empire? People have been talking about this for three decades now. Does it require years and years of peaceful development? A national idea painstakingly formulated by spin doctors in political science labs? A bourgeois revolution? Or maybe just a small victorious war? The so-called special military operation in Ukraine, which has grown into a global military and political conflict, poses these questions in a new light.

In our view, large-scale social changes are happening inside Russia today, changes which could help shape a new national project.

These changes are not always so easy to spot.

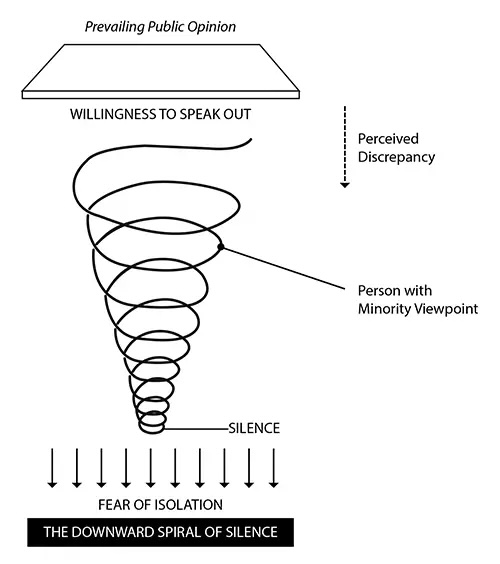

According to the social critique prevalent in the independent media, wartime Russian society is organized roughly as follows. Its freedom-loving segment has been crushed and disoriented, while its loyalist segment is atomized and under the thumb of government propaganda, which preaches xenophobia, imperialism and cynicism. Society is fragmented and polarized, suspended somewhere between apathy and fascism. But these tendencies, which are certainly important — and therefore visible to the naked eye, as well as exaggerated by the liberal discourse — are nevertheless not absolute and probably are not even the most important. Society lives its own life, meaning that different groups within it live their own lives and move in their own directions. When you analyze the trajectories of that movement you get a better sense of the major pathways along which these groups might in the future coalesce into a new nation.

Despite the official rhetoric about unity during the war years, the regime has not managed to consolidate a nation, but it has laid the groundwork for its formation in the future. This has been significantly aided by the west’s anti-Putin policies and the information war waged by the new Russian emigration’s radical wing, which speaks of the collective guilt of all Russians, of their culture and language. Consequently, the only alternative to Putinism and war has seemed to be the disenfranchisement of all Russianness, and the only alternative to official government patriotism has been the “fall of the empire.” Meanwhile, there have been and continue to exist images of the country and modes of attachment to it which cannot be reduced to either of these two options.

THE NEW RUSSIAN PATRIOTISM

The idea of a new Russian identity was expressed succinctly by Boris Yeltsin on 22 August 1991, when he said that the attempted coup had targeted “Russia, her multi-ethnic people” and her “stance on democracy and reform.” The new modern Russian identity was supposed to be the result of choosing Europe, overcoming the archetypes of slavery and subjugation, and transcending the legacies of the October Revolution, interpreted as a criminal conspiracy and lumpenproletarian revolt, and of the Soviet nation as a grim community of “executioners and victims.”

Ultimately, though, it was the reforms themselves, along with the trauma of losing a powerful state, that generated Soviet nostalgia and a new version of Stalinism. [Yeltsin’s] shelling of the [Russian Supreme Soviet] in 1993 and the dubious 1996 presidential election, which many initially regarded as a triumph for the liberal project, proved to be its doom.

Despite the fact that advocates of the radical anti-liberal revanche were momentarily defeated and exited the scene, widespread disappointment and depoliticization was a barrier for further democratization through people’s involvement in politics. The story of 1991 spoke clearly about what the new Russians could take pride in: victory over the revanchists, for which they had taken to the streets and sacrificed the lives of three young men. Subsequently, amid the chaos and bloodshed of 1993, two ideological projects of Russian identity took shape which were mostly in competition with each other, splitting civil society in the period that followed.

LIBERALS VS. THE RED-BROWN COALITION

Vladimir Putin was nominated to strengthen the new capitalism and prevent a “Soviet revanche.” But his most successful project, as was quickly revealed, actually lay in the Soviet legacy’s partial rehabilitation. Putin managed to bridge the gap of 1993: he drew in part of the pro-Soviet audience (by using patriotic rhetoric, bringing back the Soviet national anthem, and taking control of the Communist Party) and drove the most intransigent liberals and democrats into the marginal opposition. The grassroots yearning for a revival of statism, which had taken shape in the early 1990s, was gradually incorporated into the mainstream. Many years later, this enabled things that would have been impossible to imagine even during the Brezhnev era, let alone during perestroika: the erecting of monuments to Stalin, the creeping de-rehabilitation of Stalinism’s victims, the normalization of political crackdowns as the state’s defense mechanism, and, consequently, a greater number of political prisoners than during the late-Soviet period.

Today’s ideal Russians, in Putin’s eyes, are those who identify themselves with all of Russian history from Rurik to the present, see that history as one of continuous statehood, and regard the periods of turmoil (the early sixteenth century, post-revolutionary Russia, the 1990s) as instances of outside meddling which should never be repeated.

The ideological struggle over Russia’s image during the Yeltsin and Putin years was thus rooted in the opposition between the liberal narrative (based on Yeltsin’s reforms) and the Stalinist great power narrative. Putinism, which is institutionally rooted in the Yeltsin legacy, acted as a kind of arbiter in the argument between the Shenderovich and Prokhanov factions, but gradually dissolved 1993’s great power Stalinist and White Russian imperial legacy into semi-official rhetoric.

But was this semi-official rhetoric part of the national identities of ordinary Russians? Or were their national identities not so thoroughly ideologized?

Did most of the country’s citizens even have national identities during early Putinism, which deliberately atomized and depoliticized society?

THE ESCALATION OF NORMALITY

Amid the relative prosperity, socio-economic progress, and apoliticality of the 2000s we see the emergence of a new, rather de-ideologized, “normal” everyday patriotism, involving a decent life, good wages, and an image of the country which made one proud rather than ashamed. Research by the sociologist Carine Clement has shown that this brand of patriotism could be socially critical and emerge from the lower classes (who criticized the authorities for the fact that far from everyone enjoyed good wages), but could also be more loyal to officialdom and come from the middle classes (who believed that the country had on the whole achieved a good standard of living, or had created conditions for those who actually wanted to achieve it).

In any case, early Putinism depoliticized and individualized society, neutralizing the civic conflict between the liberals and the “red-brown coalition,” but one outcome of this ideological neutralization was that it brought into focus something given to citizens by default: their connection to the motherland. This connection is not conceptualized through belonging to one ideological camp or another. It is grasped through one’s sense of the value possessed by a normal, decent life, a life which all the country’s citizens deserve individually and collectively.

This value was politicized after 2011. The Bolotnaya Square protests launched a peculiar mechanism: the escalation of normality. One author of this article recently decided to go back and re-analyze the interviews PS Lab did with people who protested in support of Navalny in 2021. The analysis showed something interesting: the most “radical” protesters, the people most willing to be detained and arrested, who wanted to go all the way and topple Putin, turned out to be the most “normal.” They were middle-class people whose demands were measured and respectable.

They did not dream of building utopias or radically restructuring society, but of a parliamentary republic and combating corruption. Both the Bolotnaya Square and post-Bolotnaya Square democratic movements, including the Navalny supporters, transformed the reasonable demand for a normal, bourgeois, prosperous country into the battle standard of a heroic revolutionary struggle against the Putin regime. Navalnyism, meanwhile, also integrated a measured social critique of inequality into its agenda.

The “normal patriotism” of the lower and middle classes thus became a stake in a fierce political struggle.

The new patriotic pride might have said something like this: “We can expose and vote out corrupt officials, push back against toxic waste dumps and insane development projects, vote in solidarity, and hit the streets to protest for the candidates we support whom Moscow doesn’t like. We have people who look to the west, people who miss the USSR, and people who defended the White House in 1991 and in 1993. We face Putin’s truncheons and paddy wagons together, and together we demand democratic freedoms and social justice.” This was how a civil society made up of Navalny fans, radical communists, and regional movements might have fought together for a “normal” country, how they might have shaped the political project of a vigorous nation pursuing solidarity. They might have done it, but they didn’t have time. They did manage to piss off the Kremlin, though.

In response, the regime launched its own escalation of normality. On the one hand, it responded to the protests with radically conservative counterrevolutionary propaganda and crackdowns. On the other hand, behind the façade of radical conservativism, Putinism erected its own edifice of “normality,” which would prove to be truly durable. Beginning in 2011, the Kremlin appropriated part of the Bolotnaya Square agenda not only in its slogans but also in practice by improving the quality of the bureaucracy, raising living standards, technocratically upgrading public amenities, and advancing technological progress. Sobyanin’s Moscow was the testing ground and façade of a new normalization which involved no democracy at all.

But the real escalation of normality on the Putin regime’s part occurred when the special military operation kicked off in 2022.

WAR, (AB)NORMALITY, AND PATRIOTISM

The war has been something profoundly abnormal for many people. It has meant a break with normal life and with any hopes for a normal country. This is what the war has meant for many people, but not for all of them.

PS Lab’s research has shown that a segment of the Russian populace, the middle-class economic beneficiaries of the new wartime economic policy, argue that Russia is now approaching the image of a normal country, even if they do not support the war. According to them, it is not the war per se but the concomitant economic progress (visible, for example, in the growth of wages and the creation of jobs) and the strengthening of national identity which have finally put paid to the period of crisis and launched a stage of growth.

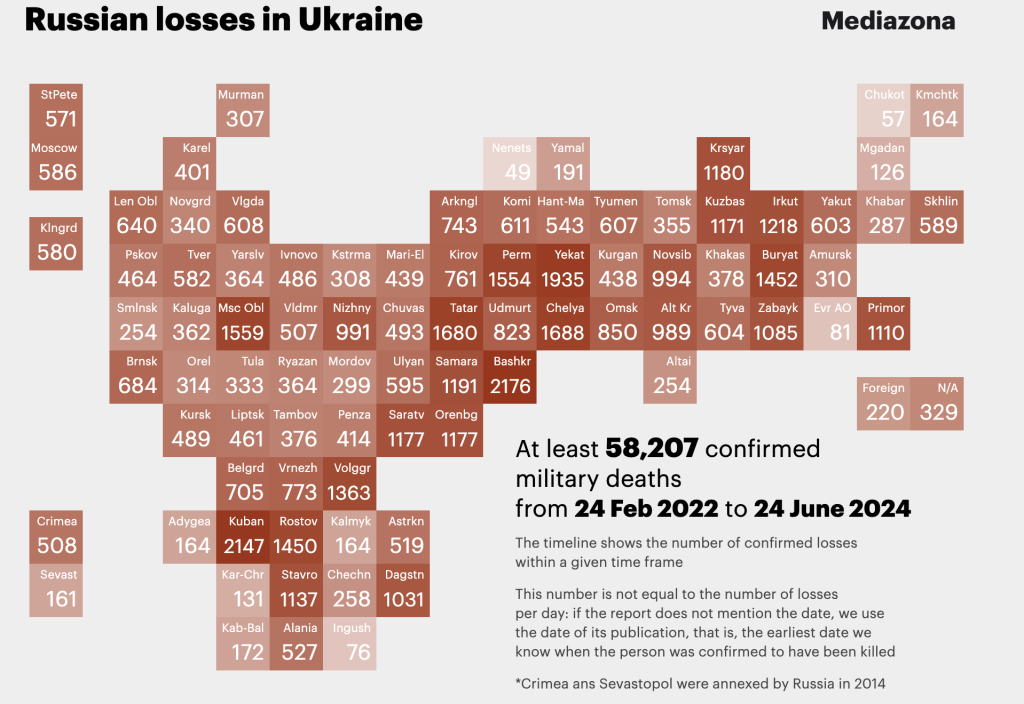

Their argument goes like this. They do not know the reasons behind the tragic special military operation, which has taken tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of lives, but in trying to cope with this tragedy, they have strengthened the Russian economy and become more patriotic.

What matters is that the idea of growth is firmly separated, in the minds of such people, from the official “goals and objectives” of the special military operation and its ideological framework. It transpires that heavyweight official patriotism is digested by a significant part of society in a milder form. PS Lab’s respondents claim that they do not support violent methods of resolving foreign policy conflicts and are indifferent to the annexation of new territories, but that it has been a good thing that they have begun to think more about the motherland.

Wartime Putinism has two faces, in other words. On the one hand, we see war, increasing crackdowns, and spasms of neo-imperialist ideology. On the other, Russians are not overly fond of those things. They value other things more, such as economic growth and the strengthening of national identity, which unites the segment of society who feel alienated by the state’s ideological and foreign policy projects. When thinking about their own patriotism, many Russians underscore the fact that it is not defined by imperialist ideology. The country is going through a difficult moment, so would it not be better for Russia to take care of itself, rather than worry about acquiring new lands? This has been a leitmotif in many interviews done by PS Lab.

Economic nationalism in the guise of military Keynesianism and the sense of community experienced by citizens going through trials (in their everyday lives, not in terms of ideology) have thus laid the foundations less for an imperial project, and more for the formation of a “normal” nation-state.

Nor is the issue of democracy off the table: it has been missed not only by the opponents but also by the supporters of the special military operation. We welcome the growth of a sovereign economy, but if Putin strangles civil society and lowers the Iron Curtain, we will be opposed to it, say the quasi-pro-war volunteers. For them, however, Putin remains the only possible guarantor of a “normal” future. Many Russians who want an end to the war and a future life without upheaval have pinned their hopes on the president for years.

This focus on gradually developing and civilizing the country is nothing new. Since the 1990s, part of the intelligentsia and, later, the new middle class, pinned their hopes first on the reforms of the pro-market technocrats, then on the successes of a then-still-liberal Putinism, then on Kudrin’s systemic liberals, then on Sobyanin’s policies, and so on.

Something went wrong, and many of these people are now in exile, but it is quite natural that images of a normal life and a normal country, albeit in radically altered circumstances, continue to excite Russians. Normality can be politicized, however, as it was between 2011 and 2022.

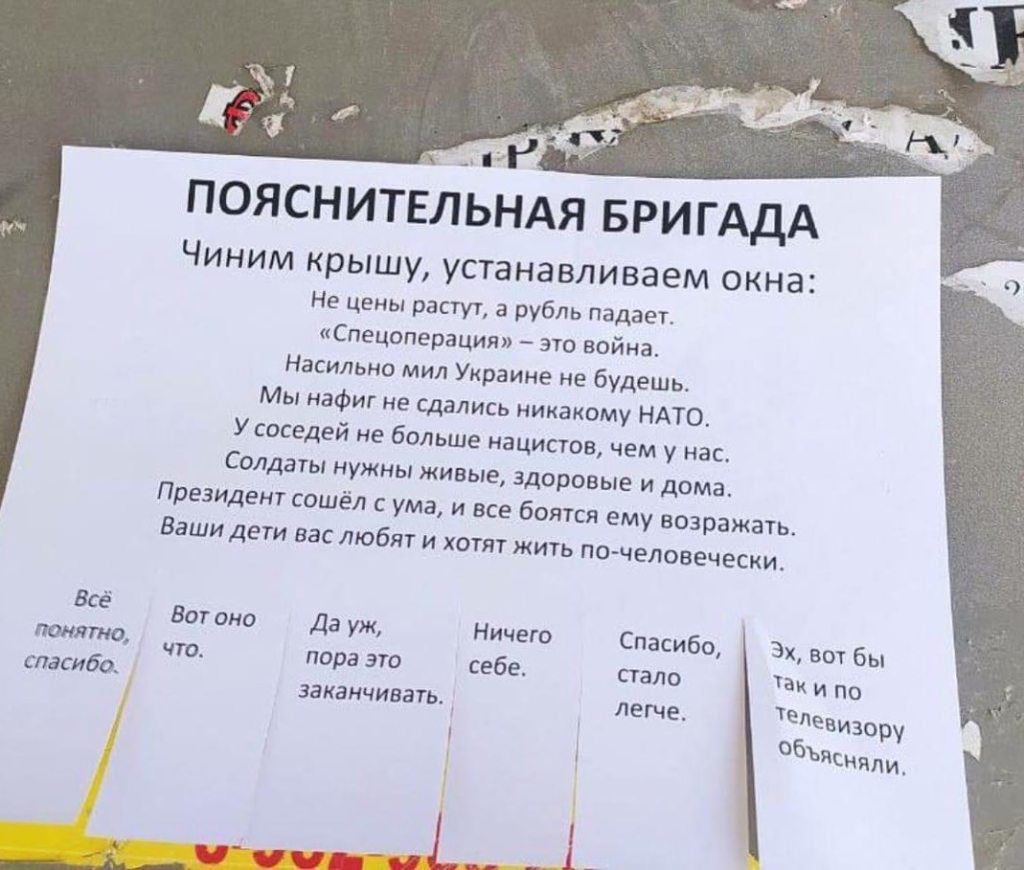

The social movements and the independent opposition which emerged after the Bolotnaya Square uprising have been virtually destroyed by the regime: the last bright flashes of this tradition faded before our eyes at the 2022 anti-war rallies. Nevertheless, the tradition of democratic protest continues. As before the war, the latter can grow from the demand for normalcy.

Moreover, the demand for normalcy can sound particularly radical in wartime.

The hardships of war have given rise to movements such as The Way Home, whose activists, wives of mobilized military personnel, have evolved from human rights loyalism to collective protest as they have demanded a return to normal life. Starting with individual demands for the protection and return of their loved ones from the front, they then arrived at a national agenda of fighting for a “normal” and even “traditional” country in which every family should have the right to a dignified, happy and peaceful life.

After a period of struggle between the two versions of patriotism born in the 1990s, liberal and neo-Soviet, the time for everyday “normal” patriotism has thus dawned. Initially, it existed as a public mood which was not fully articulated, but subsequently we witnessed a mutual escalation of normality on the part of warring protesters and the Kremlin.

The “post-Bolotnaya” opposition, led by Navalny, launched a revolutionary struggle with the regime over the project for a “normal” bourgeois country, attempting to create a broad movement that would reach far beyond the former liberal crowd. In response, the Kremlin unveiled its neo-imperialist militarist project with one hand, while with the other hand it satisfied the public demand for normality on its own after the opposition had been defeated.

TWO SCENARIOS FOR A NORMAL RUSSIA

The above-mentioned contradictions of the Putinist discourse and the complex realities of wartime (and the postwar period?) allow us to imagine two scenarios for society’s growth, the realization of two images of Russian patriotism. In other words, we see two scenarios for a socio-political dynamic which could culminate in the creation of a new nation.

Military Putinism, contrary to its radically imperialist image, has in terms of realpolitik and public sentiment put down certain foundations for the formation of a nation-state in Russia.

If economic growth, redistributive policies, and the strengthening of everyday patriotism continue after the end of the war and captivate the majority or at least a significant segment of society, the project of turning Russia into a nation-state from above will have a chance.

Whether it materializes depends on many unknowns. Will the government be able to maintain economic dynamism after dismantling the wartime economy? Will everyday patriotism turn into a solid ideological edifice? Will the end of the war be followed by a liberalization of political life? (Is this possible at all?) Will the current pro-war and anti-war volunteerism serve as the basis for an industrious, widespread civil society? Will there be a change of elites?

Russia’s transformation into a nation-state under these circumstances would constitute a serious paradox. It would thus emerge not after a lost imperialist war or a war of national liberation, but in the wake of a partly successful war, which evolved from an imperialist war into a nationalist war. What would hold such a society together?

It is easiest to envision an identity based on Russia’s opposition to the west on the basis of geopolitical confrontation or economic and technological competition, especially if a fierce struggle between newly emerging geopolitical blocs lies ahead. This confrontation with the west, which we allegedly have pulled off with dignity (even if we are willing to recognize the special military operation itself as a dubious event), will be accompanied by various practices and emblems of cultural uniqueness.

But will this new nation be capable of producing a powerful culture, as in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? Or will this future Russia be doomed to cultural and intellectual degradation as presaged by Dugin’s philosophy and pro-war poetry?

There are serious doubts that the grounds listed above would be sufficient for a multi-ethnic and multicultural entity like the Russian Federation to turn into a national community united by an understanding of a common destiny and values. The USSR as a community was based on the complex mix of the new Soviet individual and Russocentrism that took shape in the Stalinist period. The roles of this dynamic duo are currently played by the adjective rossiyskiy, which is a designation of civic membership in a multi-ethnic community, and the similar-sounding adjective russkiy, which is a grab bag of several easily manipulated meanings.

Putin is responsible for regular messages about multi-ethnicism, while numerous actors in the government and the loyalist media are charged with sending signals about Russian ethnicism. In this bizarre system, ethnic Russians, on the one hand, constitute a “single nation” with Belarusians and Ukrainians; on the other hand, they vouchsafe the coexistence of hundreds of other ethnic communities, supposedly united by “traditional values” (and, no matter how you look at it, the most important of these values is the rejection of homosexuality); while, on the third hand, they have a special message for the world either about their own humility, or about the fact that they will soon “fuck everyone over” again.

This complex edifice has been looking less and less persuasive. The zigzags and wobbles of the political top brass — Russia has swerved from alliances with North Korea and China to newfound friendship with the United States; from casting itself as a global hegemon to posing as an aggrieved victim — do nothing to help Russians understand who we are. They have, however, stimulated the growth of local, regional, ethnic narratives and identities which are much more reliable and comfortable. Ethnic brands, music and art projects involving folkloric reconstructions, the vogue for studying the languages of the peoples of the Russian Federation, and the plethora of Telegram channels about ethnic cultures and literatures are all outward signs of the new ethnic revival. Although they do not seem as provocative as the forums of radical decolonizers, they correspond less and less with a vision in which ethnic Russianness is accorded a formative role, while “multi-ethnicity” is relegated to a formal and ceremonial role.

When we draw parallels with the Soviet identity, we should remember that it was based not simply on a set of ideological apparatuses (as the current fans of censored patriotic cinema and literature imagine), but on a universal idea of the future, on the radical Enlightenment project of involving the masses and nations in history (including through “nativization” and the establishment of new territorial entities). The project had many weaknesses from the outset, and it was radically undermined by the deportation of whole ethnic groups and the anti-Semitic campaign (for which the current regime has less and less desire to apologize), but as the British historian Geoffrey Hosking has argued, the fundamental reason for the Soviet Union’s collapse was the lack of civil institutions in which the emerging inter-ethnic solidarity could find expression.

If an ethnic cultural and regional revival really awaits us amid war trauma, confusion, possible economic problems, and the deficit of a common identity, how would Moscow handle it? Would it try to control or guide the process? Or maybe it would focus on loyal nationalists and fundamentalists in a replay of the Chechen scenario? This may turn out to be a prologue to disintegration, or it may serve as the field for establishing new community. The radical democratic opposition, once it has a chance, would simply have to combine local, regional, and ethnic cultural demands with general social and democratic ones.

It is for the sake of this that we must rethink the imperial legacy, the Soviet project with its complex mix of colonialism, federalism and modernization, the way communities have lived together for centuries on this land, sometimes fighting and competing, sometimes suffering from each other and from Moscow, sometimes evolving, and sometimes coming together to fight the central government (as during the Pugachev Rebellion).

This combination of civil struggle and intellectual reflection can not only generate a fresh political counter-agenda but also reanimate the worn-out leitmotifs and narratives of Russian culture.

It can reintroduce the productive tension and contradiction, the universality inherent in a great culture, which the regime, while oppressing and exiling critical voices, has been trying to replace with an emasculated, captive patriotism.

***

We want a quiet private life without upheaval, the life which generations of Russians have dreamed of; we want to be independent, stick to our roots and remain who we are, says one group of our compatriots.

We want to overcome dictatorship, political oppression, inequality, corruption and war; we want to live in a society based on freedom and solidarity, says another group of our compatriots.

Interestingly, both of these scenarios are revolutionary. The first scenario, despite its adoration of technocracy and the petit bourgeois lifestyle, is the result of an anti-democratic revolution from above, during which the authoritarian regime has been transformed from a predominantly technocratic to a counter-revolutionary one and has challenged both the world order and the domestic political order. The abrupt transition to a redistributive military Keynesian macroeconomic policy, which was unthinkable ten years ago, and which fuels the current workaday patriotism, has emerged as part of the war. The war itself has been the decisive event of Putin’s counterrevolution, which, like any counterrevolution, always bears certain revolutionary traits.

But while the first scenario (albeit with a new, rather sinister twist) epitomizes the long-standing dream of a bourgeois life based on comfort and tradition, the second draws on a more grassroots and rebellious vision of social progress and related practices. It hearkens back to the defenders of the Russian White House in 1991 and 1993, the protesters against the monetization of benefits and the Marches of the Dissenters, the radical segment of the Bolotnaya Square movement, and the street movements in support of Navalny and Sergei Furgal. History, including Russian history, knows many such examples of new national communities emerging in radical joint struggles for democracy and justice.

Both scenarios could be generated by the current catastrophic reality, and both are fraught with fresh dangers: the first with the threat of a new descent into fascism, the second with violent civil conflicts. In our opinion, though, it is these two scenarios which shape the field for analyzing, discussing and imagining the country’s future.

Source: Kirill Medvedev and Oleg Zhuravlev, “The Russian nation’s (post)war future,” Republic, 9 March 2025. Translated by the Fabulous AM and the Russian Reader