Three Last Address plaques on the house at 27 Dostoevsky Street, in downtown Petersburg

Three Last Address plaques on the house at 27 Dostoevsky Street, in downtown Petersburg

Squealing on the Executed: Who Wants to Remove the Last Address Plaques?

Tatyana Voltskaya

Radio Svoboda

December 6, 2018

Alexander Mokhnatkin, a former aide to Russian MP Vitaly Milonov, filed a complaint with the Petersburg authorities, claiming the plaques mounted on houses throughout the city by Last Address had been erected illegally.

The plaques are barely visible from only ten meters away.

The plaques are barely visible from only ten meters away.

Andrei Pivovarov, co-chair of the Petersburg branch of Open Russia, wrote about the complaint on his Facebook page.

The city’s urban planning and architecture committee has already reacted to the complaint. It said the plaques, which bear the names of victims of Stalin’s Great Terror and have been placed on the walls of the houses where they lived just before their arrests and executions, were illegal.

There are two more plaques right next door, in the gateway of the house at 27 Dostoevsky Street.

There are two more plaques right next door, in the gateway of the house at 27 Dostoevsky Street.

“The informer decided the plaques were illegal advertisements? I wonder what for. The Stalinist Terror? He thinks they should be taken down. The Smolny responds to the snitch by indicating there were no legal grounds for putting the plaques up, and special city services would deal with them. It is difficult to guess when the wheel of the bureaucratic machine will turn, but, as Solzhenitsyn wrote, the country should know its snitches. I introduce you to Alexander Mokhnatkin, a man who has denounced people long ago victimized by the state and executed, and who has denounced the memory of those people,” Pivovarov wrote.

Unaware of the Last Address plaque on the wall next to her, a woman walks down Poltava Street, just off Old Nevsky, on a sunny day in October.

Unaware of the Last Address plaque on the wall next to her, a woman walks down Poltava Street, just off Old Nevsky, on a sunny day in October.

MP Milonov argues his former aide’s opinion is his personal opinion. Milonov, on the contrary, welcomes memorial plaques, but he does not like the fact that, currently, ordinary citizens have taken the lead in putting them up. He believes it would be better to let officials take the lead.

“I don’t think it would be good if there were lot of plaques on every house, as in a cemetery. The right thing to do, probably, would be to adopt a government program. The plaques would be hung according to the rules of the program, and protected by the law and the state,” argues Milonov.

When you step back ten or fifteen meters, the same plaque is nearly invisible to the naked eye.

When you step back ten or fifteen meters, the same plaque is nearly invisible to the naked eye.

He argues what matters most is “remembering the grandfathers of the people who now call themselves liberals squealed on our grandfathers and shot our grandfathers. Our grandfathers did not squeal on anyone. They died on the Solovki Islands. They were shot in the Gulag and various other places.”

Milonov admits different people wrote denunciations, but he believes the International Memorial Society has deliberately politicized the topic, using the memory of those shot during the Terror for their own ends. The MP argues that erecting memorial plaques should not be a “political mom-and-pop store.” Milonov fears chaos: that today one group of people will put up plaques, while tomorrow it will be another group of people. To avoid this, he proposes adopting official standards.

A Last Address plaque in the doorway of the house at 36 Razyezhaya Street, in Petersburg’s Central District.

A Last Address plaque in the doorway of the house at 36 Razyezhaya Street, in Petersburg’s Central District.

On the contrary, Evgeniya Kulakova, an employee of Memorial’s Research and Information Centre in Petersburg, stresses that Last Address is a grassroots undertaking. An important part of Last Address is the fact that the installation of each new plaque is done at the behest of private individuals, who order the plaques, pay for their manufacture, and take part in mounting them. Kulakova regards Milonov’s idea as completely unfeasible, since the municipal authorities have their own program in any case. The program has its own concept for commemorating victims of political terror, and the authorities have the means at their disposals to implement it. Last Address, however, is hugely popular among ordinary people who feel they can make their own contribution to the cause of preserving the memory of the people who perished during the Terror.

A Last Address plaque in the archway of the house at 6 Socialist Street, in central Petersburg.

A Last Address plaque in the archway of the house at 6 Socialist Street, in central Petersburg.

Kulakov thinks it no coincidence Mokhnatkin has brought attention to the Last Address plaques, since previously he had taken an interest in the Solovetsky Stone in Trinity Square. Apparently, his actions are part of a campaign against remembering Soviet state terror and the campaign against Memorial.

Many Memorial branches in Russia have been having lots of trouble lately. In particular, Memorial’s large annual Returning the Names ceremony in Moscow was nearly canceled this autumn, while the Petersburg branch has been informed that the lease on its premises has been terminated. It has been threatened with eviction as of January 6, 2019.

Three Last Address plaques, barely visible from the middle of the street, on the house at 69 Chernyakhovsky Street, near the Moscow Station in Petersburg.

Three Last Address plaques, barely visible from the middle of the street, on the house at 69 Chernyakhovsky Street, near the Moscow Station in Petersburg.

Historian Anatoly Razumov, head of the Returned Names Center, supports the concept of memorial plaques. He stressed they are installed only with the consent of building residents and apartment owners, and ordinary people welcome the undertaking. Moreover, people often put up the plaques not only to commemorate their own relatives but also to honor complete strangers whose lives have touched them. Razumov says people often find someone’s name in the Leningrad Martyrology. They then get written confirmation the person lived in a particular house. Only after collecting information about the person and obtaining the consent of the building’s residents do they erect a plaque.

“In Europe, such things are always under the protection of municipal authorities. I think we should also be going in the other direction: local district councils should do more to protect the plaques instead of saying they don’t meet the standards and they’re going to tear them down,” the historian argues.

Razumov argues that inquiries like the inquiry about the legality of the memorial plaques are served up under various attractive pretexts, but they are always based on the same thing: the fight against remembering the Terror. Some people want to preserve this memory forever, while others do everything they can to eradicate it by concocting hybrid or counter memories.

The plaques at 69 Chernyakhovsky Street commemorate Vasily Lagun, an electrician; Solomon Mayzel, a historian of the Arab world; and Irma Barsh. They were executed in 1937–1938 and exonerated of all charges in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The plaques at 69 Chernyakhovsky Street commemorate Vasily Lagun, an electrician; Solomon Mayzel, a historian of the Arab world; and Irma Barsh. They were executed in 1937–1938 and exonerated of all charges in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Boris Vishnevsky, a member of the St. Petersburg Legislative Assembly, argues that Last Address and Immortal Regiment are the most important popular undertakings of recent years. He is outraged by attempts of officials to encroach on them. He says he has written an appeal to the city’s urban planning and architecture committee.

Translation and photos by the Russian Reader

Three Last Address plaques on the house at 27 Dostoevsky Street, in downtown Petersburg

Three Last Address plaques on the house at 27 Dostoevsky Street, in downtown Petersburg The plaques are barely visible from only ten meters away.

The plaques are barely visible from only ten meters away. There are two more plaques right next door, in the gateway of the house at 27 Dostoevsky Street.

There are two more plaques right next door, in the gateway of the house at 27 Dostoevsky Street. Unaware of the Last Address plaque on the wall next to her, a woman walks down Poltava Street, just off Old Nevsky, on a sunny day in October.

Unaware of the Last Address plaque on the wall next to her, a woman walks down Poltava Street, just off Old Nevsky, on a sunny day in October. When you step back ten or fifteen meters, the same plaque is nearly invisible to the naked eye.

When you step back ten or fifteen meters, the same plaque is nearly invisible to the naked eye. A Last Address plaque in the doorway of the house at 36 Razyezhaya Street, in Petersburg’s Central District.

A Last Address plaque in the doorway of the house at 36 Razyezhaya Street, in Petersburg’s Central District. A Last Address plaque in the archway of the house at 6 Socialist Street, in central Petersburg.

A Last Address plaque in the archway of the house at 6 Socialist Street, in central Petersburg. Three Last Address plaques, barely visible from the middle of the street, on the house at 69 Chernyakhovsky Street, near the Moscow Station in Petersburg.

Three Last Address plaques, barely visible from the middle of the street, on the house at 69 Chernyakhovsky Street, near the Moscow Station in Petersburg. The plaques at 69 Chernyakhovsky Street commemorate Vasily Lagun, an electrician; Solomon Mayzel, a historian of the Arab world; and Irma Barsh. They were executed in 1937–1938 and exonerated of all charges in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The plaques at 69 Chernyakhovsky Street commemorate Vasily Lagun, an electrician; Solomon Mayzel, a historian of the Arab world; and Irma Barsh. They were executed in 1937–1938 and exonerated of all charges in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

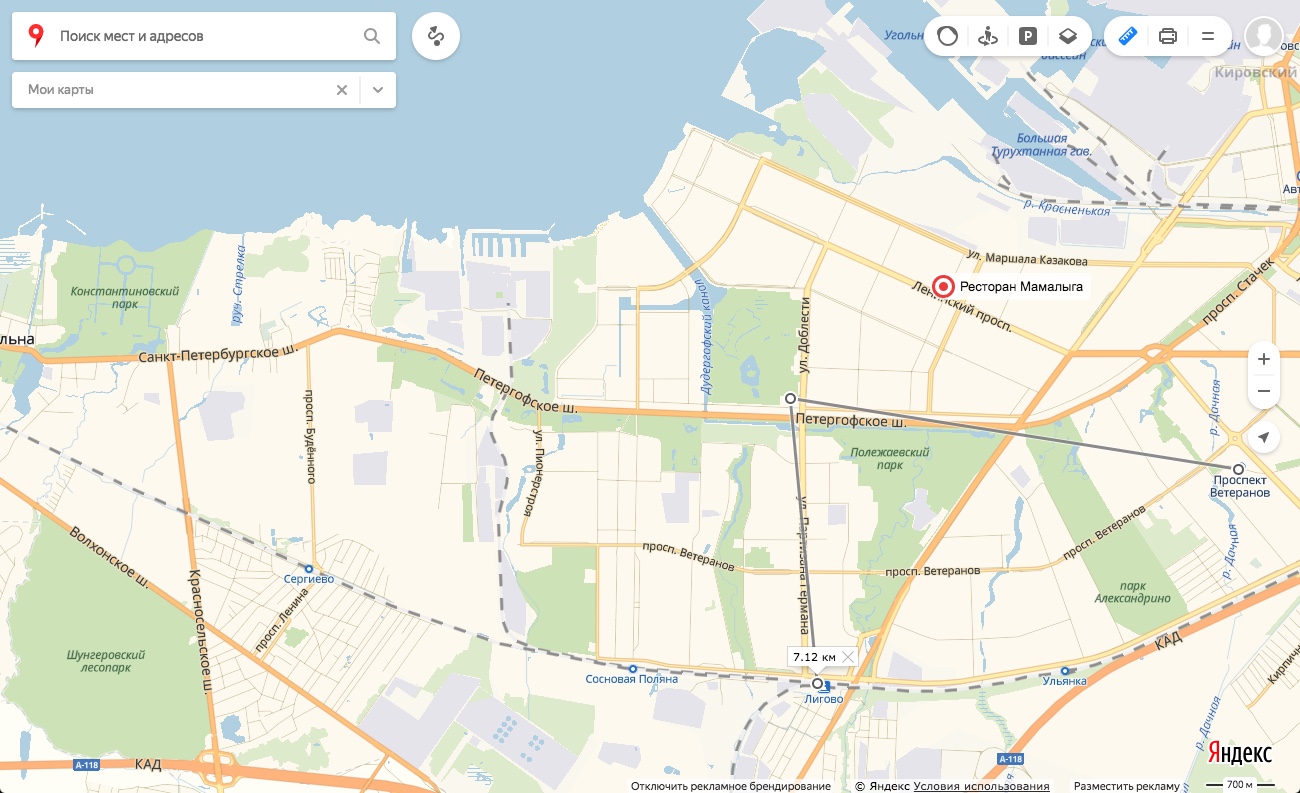

Yuzhno-Primorsky Park is located in the far southwest of Petersburg. It is four kilometers from the nearest subway station, and three kilometers from the nearest suburban railroad station. Map courtesy of

Yuzhno-Primorsky Park is located in the far southwest of Petersburg. It is four kilometers from the nearest subway station, and three kilometers from the nearest suburban railroad station. Map courtesy of