Ilya Orlov

The Field of Mars: Revolution, Mourning, and Memory

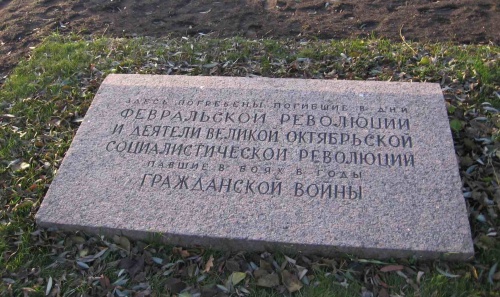

We are on the Field of Mars in Petersburg, at the Monument to the Fighters of the Revolution. That is the official name. The question immediately arises: to the fighters of which revolution? This is not specified in the official name. The epitaphs, penned by the first Soviet minister of education Anatoly Lunacharsky in 1919, are more lyrical than informative, referring to previous revolutions and historical figures, including the Jacobins and the Paris Communards. Only this humble gravestone refers to the primordial event: here lie the victims of the February Revolution of 1917.

I doubt whether anyone pays attention to this gravestone. If you ask passersby what this place is, they are likely to reply that it is some memorial to the victims of some revolution. This is not surprising. Historically, the October Revolution eclipsed the February Revolution. This eclipse happened in Soviet times, and it was reflected in Soviet historiography. And there have been so many other historical events subsequently that now society has almost no memory of this revolution and its victims. In the 1990s, students from the nearby Institute of Culture grilled sausages over the eternal flame at the center of the monument. I have heard such stories firsthand. Perhaps this was a spontaneous denial of Soviet monumentalism and Soviet ideology. But the paradox is that this monument, which was more a revolutionary than a Soviet monument, was created by the revolution. Not to glorify state ideology, but on the contrary, to memorialize those who fought against the state’s tyranny. In this sense, the Field of Mars is a “place of memory, overgrown with grass,” despite this imposing granite monument.

But the shape of the memorial dates to March 1917. Here we see four L-shaped stelae: they were built a year later, in 1918. The L-shape is not accidental. Under the stelae are four L-shaped mass graves containing 184 victims of street fighting between protesters and police in February 1917. The rest of the burial ground—the quadrangular space formed by the stelae—was established soon afterwards, but during a completely different period, after the October Revolution of 1917. Here lie a number of combatants in the Civil War, mostly Bolsheviks, and most of their names are known. Our task today is to recall the original tenor of this memorial site, the tenor of February and March 1917.

The February Revolution was the first of two revolutions in Russia in 1917 (although some historians consider them parts of a single revolutionary process). After spontaneous bread riots, mass strikes and demonstrations in Petrograd (then the capital of the Russian Empire), soldiers from the city’s garrison sided with the protesters. The revolution resulted in the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. The Provisional Government came to power, its members, mostly liberals and conservatives, drawn from the State Duma (the former monarchy’s parliament). At the same time, local socialists formed an alternative authority, the Petrograd Soviet, which ruled alongside the Provisional Government. There were thus two centers of power, both with problems of legitimacy. It was a very unstable situation, which Lenin defined as a diarchy (dvoevlastie).

The new authorities decreed political freedom, ended capital punishment, released political prisoners, and abolished ethnic and religious discrimination. The result was total euphoria. But such important issues as Russia’s involvement in the First World War, social and economic problems, and labor issues remained on the agenda. Also, the question of the country’s future political constitution was unclear. The new authorities were not ready to answer these questions and deferred their consideration until the future Constituent Assembly met. In 1917, the idea of the Constituent Assembly, a “future master” that would be able to solve all problems, was a sort of fetish. It was, in fact, convened in 1918, but was soon dissolved by the Bolsheviks.

So the beginning of March 1917 was a time of economic crisis and instability, a hard situation at the front, universal euphoria over revolutionary liberation, total uncertainty about the future, and potential social fissure. This is the context in which the Petrograd Soviet raised the question of organizing a gigantic nationwide political manifestation—a solemn funeral for the victims of the revolution.

Numbers

The February Revolution was not bloodless. How many people were killed or wounded? The exact number of dead and wounded has never been precisely determined. According to early Soviet historiography, the total number of casualties did not exceed one and a half thousand. Of these, no more than two hundred people were killed. In later historiography, the numbers increased. But this information is also unreliable, because not all the victims were recorded.

There is also uncertainty over the number of people buried in the mass graves on the Field of Mars. Sometimes, the figures vary even within the same newspaper article. But the maximum number found in the historical sources is 184.

The nationwide funeral of the victims of the revolution or, as it was called, the “great funeral,” was planned by the Petrograd Soviet soon after the victory of the revolution. According to their plan, it was to be a grandiose funeral demonstration, meant to unite all the forces of the revolution, a “parade and review of all the revolutionary forces.” Preparations for the ceremony took more than three weeks. The plans were finally implemented on March 23, 1917.

Contemporaries described the events of that day as completely unprecedented. From morning till late night, endless columns of demonstrators relentlessly marched from different quarters of the city to the Field of Mars, carrying red coffins containing the bodies of the victims of the revolution. One after the other, the funeral processions arrived at the Field of Mars. It was a kind of political demonstration where various political, social, ethnic, professional groups and identities were broadly represented. There were columns of workers from different factories, military units, columns from educational institutions, columns made up of workers from various professions and trades, columns from leftist parties (for example, the Social Democrats and the Socialist Revolutionaries), columns representing different ethnic groups, and columns from ethnic leftist parties, for example, the Jewish Bund and the Armenian Dashnaktsutyun party. There were also columns from grassroots organizations, civic committees, and other groups of citizens, including, even, a column of blind people. In a certain sense, it was a symbolic repetition of the revolution itself.

According to official figures, 800,000 people attended the funeral manifestation. According to unofficial tallies, up to two million people attended. Given that the city’s population was around 2.5 million at the time, we can assume the majority of the capital’s inhabitants were involved in the ceremony as participants or spectators.

There is still no historiography specially devoted to this event. The event, however, is well documented: all the newspapers published reports about it, and many photographs were taken. It is curious that photographs of the ceremony are still used as primarily visual matter for books and articles about the February Revolution, even if the funeral is not actually mentioned in them. This is quite understandable: the photographs depict a huge mass of demonstrators, as if this were the revolution itself.

The newspaper reports about the funeral are highly emotional. Sometimes, they even slip from prose into poetry. The rhetoric of “brotherhood” or “revolutionary brotherhood” is quite common in these reports: the victims of the revolution are often referred to as “our dead brothers.” At the same time, these articles have a euphoric tone: they often talk about the coming revival of the country, or about a great celebration of freedom.

Historians have repeatedly noted the anthropological connection between mourning, celebration, and revolution. Specifically, French historian Mona Ozouf talks about this in her book Festivals and the French Revolution. There are other numerous historical examples of this phenomenon, including the Ukrainian Maidan of 2014. Mourning and funeral processions provoke sublime feelings and mobilize people.

It is quite important to note one thing about this funeral. It was fundamentally a civil ceremony. There were no icons, no crosses, and no priests. Numerous requests from clergy to participate in the ceremony were rejected by the Soviet. For the first time in Russian history, a funeral of this scale was conducted without the Church’s participation. This civil ceremony was not just secular, however. It followed the cultural tradition of the revolutionary underground, the tradition of so-called red funerals. This tradition started after Bloody Sunday, the massacre of unarmed demonstrators that sparked the Revolution of 1905. Then, workers had begun to bury their comrades in red coffins, without the ministrations of priests. And more importantly, they turned funerals into political rallies. In defiance of the autocracy and the despotism of capitalism, they seemed to identify the sacred—death—as one of their allies. At the Field of Mars in 1917, this tradition attained official national status for the first time.

The ceremony of this huge demonstration was elaborately planned over several weeks. From the very beginning, it was clear the number of participants would be enormous. (As I have mentioned, it was as many as two million people in the end.) The organizers were afraid there could be a crush or stampede in the crowd. Therefore, they drew up instructions, layouts, route charts, and written rules that explained how the columns of the demonstrators should be self-organized, where and when they should start, how they should move, and which way they should go during the ceremony. These instructions were published before the funeral in newspapers.

The instructions were based on the idea of self-organization by district. Assembly points were located at the hospitals in the city’s six districts where the bodies of the victims of the revolution lay. There was a parallel between this scheme and the structure of the Soviet itself: both were democratic structures based on the representation of districts and small groups. The departure time of the district processions was scheduled in such a way that they arrived at the Field of Mars one after another, and only from the direction of Sadovaya Street.

The main idea of the ceremony’s planners was that the funeral procession would not stop in the square even for a minute. When a column reached the burial site, the demonstrators handed the coffins to workers who directly carried out the burials. The very next moment, the column would continue to move toward the exit, which was located on the opposite side of the field, near Trinity Bridge. This was done to prevent the crowd from being crushed.

Each time a coffin was lowered into a grave, a gun was fired at the Peter and Paul Fortress, on the opposite bank of the Neva River. To coordinate the movement of the columns, telephone wires were laid between the observation points.

The procession moved without stopping through the Field of Mars, and this also excluded the possibility of holding a rally. Therein lay the uniqueness of this mass commemoration: there were no public speeches during the entire ceremony, only funeral music, revolutionary songs, and lots of red flags.

Now I would like to draw your attention again to the structure of the burial ground—the four L-shaped mass graves at the corners of this large square. The funeral procession passed through the space between the graves. Alongside and above the graves, temporary wooden platforms (stages) were erected for the ceremony’s organizers and the leaders of the Petrograd Soviet. There were special hatches on the platforms for lowering the coffins into the ground.

I should emphasize that it was impossible to make a speech or address an audience there, because the procession passed through the square without stopping. So the politicians just stood silently over the graves.

This combination of burial ground and site of political power is also remarkable. In this structure, the political approaches the sacral. The sublime feeling caused by the funeral seemed to reinforce the politics. The sacral became a support for political power. This convergence of politics and mourning was continued in Soviet times, of course, in the structure of the Lenin Mausoleum, with its tribune above the tomb.

What made this large-scale ceremony possible? And why did the Petrograd Soviet devote so much attention, time, and effort to organizing this manifestation in March 1917, when they had a variety of other pressing problems on their agenda?

It was clear what society needed: the victory of the revolution had been unexpected, and such dizzying change is always traumatic. The time was as it were “broken,” and the transition to the new life requires a ritual pattern. The funeral of the victims of the revolution may have played the role of such a therapeutic ritual. It was a kind of funeral of the ancien régime, a funeral of monarchy and despotism. It was thus no wonder it actually turned into joyous celebration of freedom, as witnesses of the event described it. They often dubbed it a “funeral celebration.”

The Soviet’s task was to mobilize society. The idea of organizing a symbolic repetition of the revolution was probably an attempt to overcome chaos and make the situation more transparent. In fact, the speakers in the Soviet clearly declared their intention to arrange a “parade of revolutionary forces,” which obviously meant making these forces visible, represented in the form of a manifestation on the square.

But the more important reason, as might be expected, was the problem of the basis for the new political authorities. Both the Provisional Government and the first roster of the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet suffered from a lack of legitimacy: both were self-proclaimed revolutionary centers of power. Professional politicians had formed both. The Provisional Government had been formed by co-opting liberal and conservative members of the former State Duma. The Petrograd Soviet was made up of leftist Duma deputies and former underground leftist activists, although the Petrograd Soviet was in a somewhat better position, because its deputies had been elected. But its legitimacy had not been realized, either, because the Executive Committee had actually decided to relinquish its power, transferring most of it to the Provisional Government.

Thus, given a lack of solid ground in the present, the new authorities were forced to postpone solving the problem of legitimacy until the future, shifting it onto the shoulders of the Constituent Assembly (which was like putting it off until doomsday) or seeking support in symbolic actions and, in Leon Trotsky’s words, the “strong emotions and memories of the masses.” In fact, they tried to have it both ways. Of course, the traditional mode of sacralizing power (that is, the “divine right” of the monarch) had become impossible, so the most appropriate source of the sacral that remained was mourning—veneration of the fallen freedom fighters, the rhetoric of “sacrifice,” and so on.

Why was the Field of Mars chosen as the burial site? The funeral was preceded by a long discussion, lasting around three weeks, that took place at meetings of the Petrograd Soviet, as well as among the general public. The initial decision was to bury the victims of the revolution on Palace Square, directly in front of the Winter Palace, and for this purpose to pull down the Alexander Column. Palace Square and the Winter Palace were the very heart of the former empire, symbols of the monarchy. Palace Square was also where Bloody Sunday had taken place in 1905. To erect a memorial to the victims of the revolution in this place would have been a strong symbolic gesture, indicating the end of the ancien régime. Initially, the Petrograd Soviet voted the decision unanimously. In a revolutionary society, it was a decision that met with wholehearted support.

The next twist in the plot is almost like out of a detective novel.

Suddenly, members of the bourgeois artistic elite entered the picture. The key figures were art critic and artist Alexander Benois and the architects and artists of the World of Art group with which he was associated. This was a very influential conservative artistic movement that advocated neoclassicism and poeticized “old” Petersburg. Their objective was to maintain their influence in the realm of culture under the new government. They also wanted to establish and lead a new “Ministry of Fine Arts.” And since the architectural ensemble of Palace Square was for them the epitome of high art, they made an effort to change the Petrograd Soviet’s decision.

Through complicated intrigues, connections in the bourgeois Provisional Government, and cynical use of revolutionary rhetoric, they were able to convince the Petrograd Soviet to change their minds. Their ruse was cynical and sophisticated. They urgently drew up and submitted to the Soviet an architectural plan under which a palace to house the future Constituent Assembly would be built on the Field of Mars; hence, supposedly, the memorial to the victims of the revolution should be sited near this new building as well. They also promised the palace would be decorated with statues, “including, perhaps, statues of the current leaders of the revolution.” As a result, the Petrograd Soviet agreed to change the burial site from Palace Square to the Field of Mars.

Architect Lev Rudnev built the monument in 1918–1919. The author of the poetic epitaphs on the monument, as I have mentioned, was Anatoly Lunacharsky.

NOT VICTIMS, BUT HEROES

lie beneath this tomb

NOT GRIEF, BUT ENVY

your fate engenders

in the hearts of

all grateful

descendants

in the terrible red days

you lived gloriously

and died beautifully

THE RANKS OF THE MIGHTY

departed from life

in the name of life’s flourishing

THE HEROES OF UPRISINGS

of different ages

the crowds of Jacobins

THE FIGHTERS OF ‘48

the crowds of Communards

are now joined

by the sons of Petersburg

In the early Soviet period, the Field of Mars served as a pantheon where Bolsheviks killed during the Civil War were buried. This was before the new pantheon near the Kremlin Wall in Moscow was built.

After Stalin’s death, during the Khrushchev Thaw, official Soviet ideology attempted, in a certain sense, to return to its revolutionary origins. On the fortieth anniversary of the revolution, in 1957, an eternal flame was lit in the center of the memorial.

The fire was brought from the open-hearth furnaces of the Kirov Plant, one of the major machine-building factories in Leningrad. It was the first eternal flame in the country, and it was lit in memory of the victims of all revolutions. It was from this fire that the eternal flames at the Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery, and ten years later, in 1967, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier near the Kremlin Wall, were lit.

For the rest of the Soviet period, the memorial was one of the most important official places of memory in the country. But it was revered as a monument to “the fighters of all revolutions,” that is, there was no emphasis on the February Revolution, to which it had originally been dedicated. The memory of February was displaced by the memory of October.

In post-Soviet times, the memorial has remained unchanged, but with each passing year it is more and more obviously at odds with the official anti-communist ideology. This has especially been the case in the past few years, given the growing dominance of rightist ideology, the condemnation of all revolutions, and the denial of the revolutionary legacy’s value.

Two years ago, in 2012, an urban development project that called for eliminating the memorial was presented at the Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum. The project proposed moving the graves to another location and creating a recreational area on the Field of Mars. Once again, members of the conservative intelligentsia were involved. Local historian and journalist Lev Lurie and Alexander Borovsky, head of the Russian Museum’s contemporary art department, publicly expressed support for demolishing the memorial. The argument was as follows: the revolutionaries were villains and murderers, the revolution had long been forgotten, and Petersburgers did not have enough recreational areas. A number of historians and public figures came out in defense of the memorial. I also published an article in defense of the place. In any case, for reasons unknown, the project was canned.

Perhaps the following odd episode played a part in this outcome. That same year, 2012, the city police suddenly organized a solemn commemoration at the memorial. The official statement for this strange commemoration claimed the people buried in these mass graves were not, in fact, revolutionaries, but plainclothes gendarmes who had been killed by protesters during the street fighting in February 1917, and that these defenders of the old regime were the real victims of the revolution.

The context of these recent events has been the crackdown on political freedoms in Russia. For example, Petersburg city hall has repeatedly refused to let the opposition hold rallies in the city center. As a result of this longstanding dispute between the opposition and the municipal administration, the authorities proposed establishing a so-called Hyde Park in the city center, choosing the Field of Mars as the site.

For several years now, protest rallies have been held here. As a rule, they are not well attended: the society is intimidated and politically apathetic. The protesters include everyone from liberals and leftists to animal rights advocates. And yet the historical memory of this place has almost been lost: its revolutionary history is almost never has evoked at these rallies. Perhaps it is too far in the past, hidden under numerous layers of history. Or perhaps this is a problem of today’s political movements, which have lost their connection with this great revolutionary tradition that once triumphed in Russia.

***

It is difficult to evaluate, either positively or negatively, the practice of revolutionary commemoration, especially when it is bound up with funerals and the rhetoric of “strong emotions,” as well as the post-revolutionary infatuation with monumentalism. On the one hand, the intention of the authorities to find support for their political power in the sacral (in mourning, in sublime feelings, in the archaic) points to the fact that the government had a problem securing its legitimacy. Paradoxically, it would seem that the most advanced political system—the revolutionary soviets of 1917—could rely on archaic feelings just like the monarchy, which used to refer to its “divine right” to rule. The infatuation with monumentalism also seems like something akin to fetishism, especially when we realize that, after many years, even a heavy granite monument is unable to retain its original meaning. In a sense, this is the counter-revolutionary aspect of revolutionary culture.

On the other hand, the monumental solemnity of this forgotten mass commemoration of March 1917 seems today like valuable know-how, even a lesson for us. The commemoration that took place here in 1917 was an alternative to the commemorations of the ousted regime, both in its form and its content. It remains just as relevant today in its separation of church and state, its reverence not for heroes but for common people, and its commemoration of those who did not support but opposed the state.

Ilya Orlov (born 1973) is a Petersburg-based artist and historian. He graduated from the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences (Smolny College) of Saint Petersburg State University, where he majored in history, philosophy, political science, and art. He wrote his honor’s thesis on revolutionary mourning rituals in 1917, and his M.A. dissertation on the aesthetics of nature in contemporary curatorial studies. Orlov’s recent artistic work has focused on cultural, social, and political issues in post-Soviet reality and the politics of commemoration.

The article above is based on the text of a guided tour Ilya Orlov led to the Field of Mars in October 2014. My thanks to him for permission to publish it here and his generous assistance in locating some of the accompanying illustrations. The text was edited by the Russian Reader. Funeral photographs courtesy of humus and statehistory.ru. Photo of Elena Osipova by Sergey Chernov. Modern-day photos of the Field of Mars (except for aerial view) by the Russian Reader

Discover more from The Russian Reader

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

One thought on “Ilya Orlov: On the Field of Mars”