The Truckers’ Battle

Milana Mazayeva

Takie Dela

April 10, 2017

Our correspondent spent time with striking truckers in Dagestan and listened to their grievances against the regime.

Ali goes to the Dagestani truckers’ strike every morning. He has four children at home, two of them underage. No one in the family earns money besides Ali.

“If I don’t work, the only thing I can count on is the child support benefit my wife gets, which is 120 rubles [approx. 2 euros] a month. But the powers that be are not going to use that on me to force me to leave. I’m in it till the end.”

***

A nationwide truckers’ strike kicked off on March 27 in several regions of Russia. The authorities were quick to react. Petersburg traffic police detained Andrei Bazhutin, chair of the Association of Russian Carriers (OPR), accusing him of driving without a license. The incident occurred on the strike’s first day. Bazhutin was taken to a district court and placed under arrest for fourteen days. The sentence was later reduced to five days, and Bazhutin got out of jail on April 1.

The difference between this strike and other protests is that none of the strikers intends to give up, despite the arrests, intimidation, and blandishments meted out by the authorities.

“The arrest took five days from life and upset my family,” says Bazhutin. “Otherwise, nothing has changed about the strike. We said we were going to shut down cargo haulage, and that is what we have been doing. We said we would set up camps outside major cities, and that is what we have been doing. Next, we’re going to be holding rallies and recruiting grassroots organizations and political parties to our cause. Dagestan has been shut down, Siberia has been shut down. Central Russia is also on our side.”

“Officials Rake in the Dough, While We Eke out a Living”: What the Strikers in Dagestan Are Saying

Vakhid: Who the heck are you? What channel are you with? We don’t believe you. You won’t change anything with your articles. We need Channel One out here. Lots of folks have been here. They’ve walked around and taken pictures, and there was no point to it.

Magomed: I’m striking with my dad and our neighbor. The three of us run a rig together. We chipped in and bought it. It fed three families, but now we cannot manage. Over half the money we earn goes to paying taxes, buying diesel fuel, and maintaining the truck, and now on top of that there’s this Plato. We’re in the red. We’re staying out on strike until we win.

Ramazan: Plato has forced us to raise the prices for freight haulage. This triggers a rise in prices in grocery stores. So we’re the villains who take money from the common people and hand it over to Rotenberg? No, I disagree with this. I don’t want that sin on my conscience.

Haji: I don’t have an eighteen-wheeler. I’m a taxi driver. I came here the first day to support my brothers and then left. But then I saw on the web the riot cops had been sent in, and I decided to join the truckers and strike with them. Are they enemies of the people who should be surrounded by men armed to the teeth? Are the riot cops planning to shoot at them? What for?

Umar: I pay Plato 14,000 rubles [approx. 230 euros] for a single run to Moscow and back. It doesn’t matter whether I have a load or I’m running empty. If this goes on, I’ll have to sell the truck. I don’t really believe they’ll abolish Plato, but I have a bit of hope. If I lose my job, my eldest son will have to quit school and support the family. He’s in his fourth year at the police academy.

Anonymous: We don’t have any watch or shift method here. We gave up on the idea because the people whose toes we’re stepping on are just waiting for us to do something that would enable them to charge us with conspiracy and a group crime. We made the decision that everyone would be striking on his own behalf. We have no leaders or chairmen. In 2016, we made a mistake: we elected one person to speak on our behalf. And what happened to him? After the first meeting, he was put on the wanted list and accused of extremism.

Isa: I’m not a long-haul trucker. I have a dump truck, but I decided to take part in the strike, too, because now I have to buy a pass that costs 2,000 rubles a month. What for? I live in town, and I never drive the truck out of town. I’m not causing damage to federal roads, why am I obliged to pay more than what I pay by law? I have four children to support.

Who Started it, or, The Damage Caused by Damage Compensation

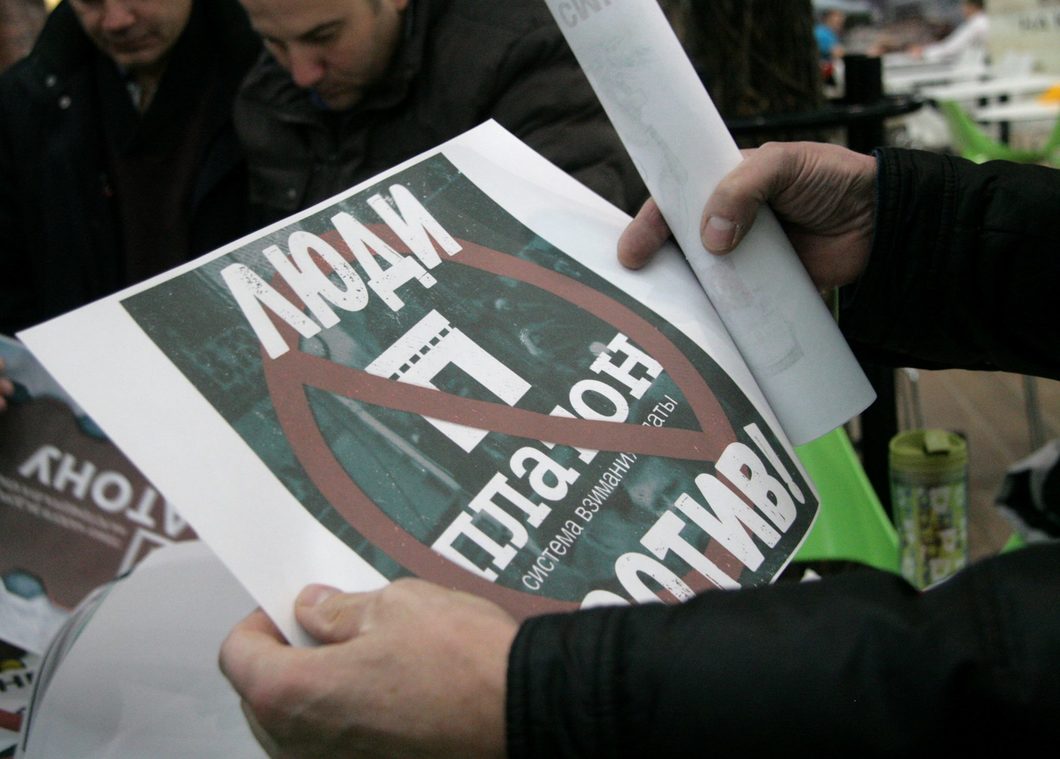

The strike was triggered by an increase in the toll rates for vehicles weighing twelve tons or more under the Plato road tolls payment system. The system was set up, allegedly, to offset the damage big rigs cause to Russia’s highways.

When Plato was launched in 2015, the rate was 1.53 rubles per kilometer. The truckers got the rate lowered to this rate through a series of protests, forcing the government to introduce discounted rates.

The second wave of protests kicked off because the rate was supposed to double to 3.06 rubles per kilometer as of April 15, 2017. After Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev met with members of the business community on March 23, 2017, the decision was taken to raise the rates by 25% instead of 50%, but the truckers did not give up on the idea of striking. According to Rustam Mallamagomedov, a representative of Dagestan’s truckers, they prepared for the strike in advance.

“I’ve been in the freight business since 2003. There were things in the past that outraged us, like rising prices and changing tariffs, but Plato has been beyond the pale.

As soon as we learned the rates would go up on April 15, we got ourselves coordinated and went out on strike. We wanted to strike on March 10, but recalling what happened in 2015, we decided to get the regions up to snuff, get in touch with everyone, and go on strike together. Before Plato was launched, we hadn’t even heard of it. We were just confronted with a done deal. Yeah, there had been articles about it on the web, but most truckers aren’t interested in news and politics. We went out on strike as soon as we realized what the deal was.”

The Truckers’ Demands: Abolishing Plato and Firing Medvedev

It is difficult to count the number of strikers. We know there are 39,000 heavy cargo vehicle drivers registered in Dagestan, and the truckers claim that nearly all of them have gone on strike. The strikers’ demands also differ from one region to the next. Only one demand is common to all regions, however: dismantling the Plato system.

“It affects each and every one of us, because prices of products will go up for end users,” Bazhutin explains. “The Plato system will be introduced for passenger vehicles, similar to Germany. Next, we have a number of professional demands, since the industry is on its knees. They include reforming work schedules, making sense of the weight and seize requirements, and generally reforming the transport sector. Our fourth point is forcing the government to resign and expressing no confidence in the president. This lack of confidence has been there and will remain in light of the fact that we have a Constititution, but the Constitution is honored in the breach. People’s rights are violated, and since the president has sworn to protect the Constitution, we have expressed our lack of confidence in him. We believe we have to do things step by step. There must be meetings, there must be dialogue.”

The Dagestani drivers’ list of demands includes access to central TV channels.

“We want to be heard,” insists Mallamagomedov. “The mainstream media are silent, although Dagestan is now on the verge of a revolution. Our guys categorically demand that reporters from the main TV channels be sent here. Only after that would they agree to communicate with the authorities.”

Timur, a member of the Makhachkala Jamaat of Truck Drivers (as they call themselves), lists, among other demand, deferred payment of loans during the strike, thus recognizing it as a force majeure circumstance. In addition, the drivers in Dagestan’s capital have demanded an end to the persecution of strikers and the release of jailed activists.

Platonic Dislike, or, Who Needs Plato?

Yuri, from St. Petersburg, has been driving an eighteen-wheeler since 1977. He has been involved in the strike since day one, going home only to shower and change his clothes. Yuri has calculations, made by a professor at the Vyatsk State Agriculture Academy, according to which the passage of one truck over a stretch of highway corresponds to that of three passengers cars, rather than sixty, as was claimed in a government report on the benefits of the Plato payment system.

When he voices his grievances against Plato, Yuri resorts to the Constitution, which stipulates that vehicles and goods should move unhindered on the roads, and forbids erecting barriers and charging fees. [I honestly could find no such clause in the Russian Constitution, but maybe I was looking in the wrong place — TRR.]

Dagestan has also prepared for the eventuality the regime will try and play on the driver’s political illiteracy. The truckers now can safely converse with officials from the Transport Ministry and defend their case by citing calculations and the constitutions of their country and regions.

“We pay the transport tax and the fuel excise tax. The average truck travels 100,000 kilometers annually,” explains Mallamagomedov. “If Plato were to charge the originally announced toll of 3.73 rubles per kilometer, that would have amounted to 373,000 rubles [approx. 6,150 euros] per year for one truck alone. The fuel excise tax amounts to ten rubles per kilometer. That’s another 400,000 rubles a year.”

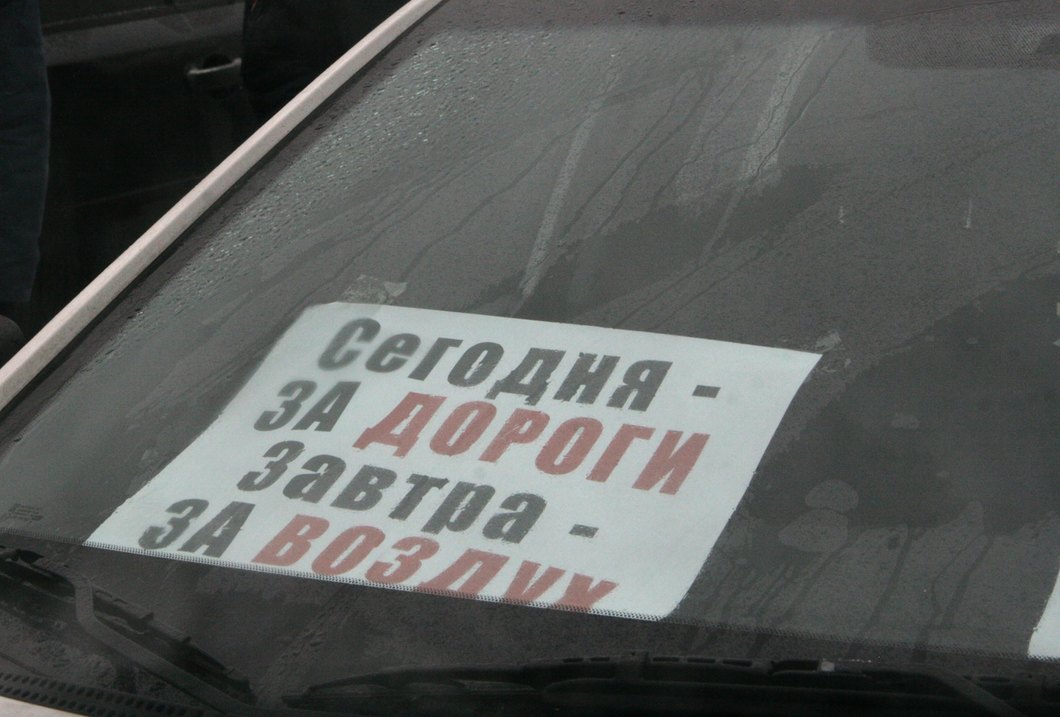

“In 2013, Putin clearly said during his annual press conference there was money to build roads. What was lacking was the facilities to build them. At the time, the regional authorities even wanted to refocus these funds on other needs. What happened in two years? Why did the money suddenly dry up? We are willing to pay if necessary. No one has a greater stake in road construction than we do. The roads damage our trucks and send the depreciation through the roof. We suggested adding one or two rubles to the fuel excise tax, rather than enrichening a private company. But what ultimately happened?

“During the past two years, four rubles have been added to the fuel excise tax and Plato has been launched. The government makes five trillion rubles [approx. 82 billion euros] a year from the excise tax alone, although one and a half trillion rubles would suffice for road construction and maintenance. But all the roads are still the same.”

Akhmat lives in the Dagestani city of Manas. It has the largest number of striking drivers, two thousand, and just as many big rigs have been shut down. Akhmat readily admits he has never paid a kopeck to Plato.

“I get fines in the mail, but I don’t pay them and I don’t intend to pay them. The money we pay through the fuel excise tax should be more than enough to fund everything. When we fuel up with diesel, we should have already paid enough to build roads.”

According to intelligence gathered by the strikers themselves, only large companies with a stake in maintaining relations with the authorities are not on strike. All the independent drivers have been striking.

“We’ve been getting information that large retail chains are already experiencing problems supplying certain food products, that cheap products have begun to vanish from the shelves, and that fruits and vegetables, which are shipped through Dagestan, have also vanished,” says Sergei Vladimirov from St. Petersburg. “I’m not going to predict how far this will go.

“What matters is that it not lead to revolution or civil war, because the people’s bitterness can come out in different ways. As citizens and fathers, we wouldn’t want this to happen. But if there is no dialogue, there will be no peace.”

Milana Mazayeva interviews a striking trucker in Dagestan (in Russian)

The possibility of losing one’s livelihood is regarded especially acutely in the North Caucasus.

“In my homeland of Dagestan, around 70% of the men earn their living behind the wheel. It is their only income,” says trucker Ali. “If a man is deprived of the means to feed his family, he’ll be ready for anything. The factories have been shut down: there is no employment in the region. Then they’ll say we’re all thieves and bandits. I’m not saying we’ll go stealing, but this system robs us of our last chance to make an honest living. What should we do? Retreat into the forests?”

Ali has been in the Manas camp for four days. During this time, he has not only failed to change his mind but he has become firmer in his intention not to back down.

“Our guys are camped out in Manas, Khasavyurt, Kizlyar, and Makhachkala.

“We stop everyone who drives by and is not involved in the strike. We ask them to join us, to show solidarity. We are certain the consequences will affect everyone. Someone cited the example of a bottle of milk. He said that, on average, the price of a carton rises by one to three kopecks. The guys who made those calculations didn’t factor in that, before the milk hits the stands in the stores, you have to feed the cow, milk it, process the milk, and produce containers. They ignored the entire logistical chain that gets the milk to the stores, talking instead about a price rise of one kopeck.

“If the authorities do not respond to our demands, people will abandon their TV sets. Television is now saying that everything is fine, and that our only problems are Ukraine and Syria. Meanwhile, the country is impoverished.”

Plato’s branch office in Makhachkala claims the strike has in no way affected its operation. There were few drivers willing to pay in the first place. Most truckers look for ways to outwit the system.

“You cannot say that registration has stopped due to the strike. But we have the smallest percentage of registration in Dagestan,” says Ramazan Akhmedov, head of Plato’s Dagestan office. “Only one to two percent of truckers out of a total of 30,000 are in our system. Everyone else claims they didn’t get the fines. The system doesn’t work if a fine isn’t received, so it means they’re not going to pay.”

“Dagestan also lacks cameras that would record violations and issue fines. They are supposed to be installed before the end of the year. Most drivers travel within Dagestan, where there are no monitoring cameras, and when it is necessary to travel outside the region, they resort to tricks: they buy a temporary package or hide their license plates.”

What the Neighbours Say: Other Countries’ Know-How

Systems similar to Plato are used in many countries around the world, but not all of them have proved their worth, argue the Russian truckers. An OPR delegation visited Germany to learn the advantages and disadvantages of their system.

“The Germans blew it all when they agreed to pay tolls via a similar system,” recounts Sergei Vladimirov. “Three big companies pushed private carriers out of their livelihoods. Then they hired them to work for them and cut their pay in half. Germany is a total nightmare at the moment. A similar system for passenger vehicles is going online as of March 24. We can look forward to the same thing.”

But the carriers said there was no comparison between the quality of the roads in Russian and the west. Obviously, such factors as geography and the condition of roads when repairs are undertaken are quite significant.

“We were told about a similar scheme for collecting tolls in Germany,” says Timur Ramazanov. “I traveled around Germany with a local carrier. Along the way, we came across repairs of a new stretch of road. When I asked him why they were repairing a new road, the driver put a full cup of water on the dashboard and sped the truck up to 160 kilometers per hour. The water in the cup was shaking. That was the reason they were repairing that section of road. It would be unpatriotic, but we should hire the Germans to build our roads.”

Ramazan Akhmedov, head of Plato’s Dagestan branch, defends the system.

“When the system was just going online, we chatted with drivers from Belarus. They told us that, at first, their system wasn’t accepted by drivers. They tried to drive around the cameras, but now everyone pays. The system has proven its worth.”

“The Regime Is Out in Left Field”: The Authorities React to the Strike

The reaction of regional authorities to the strike has been mixed. There are regions where officials attend protest rallies on a daily basis, and there are others where they have been totally ignoring the strike.

Bazhutin argues that the closer you get to the capital, the less dialogue there is.

“The authorities at home in Petersburg have reacted quite languidly for some reason. They don’t want to talk with us. But the heck with them, we’ll wait them out.”

Yuri Yashukov is not surprised by the lack of a reaction on the part of federal authorities.

“How did the regime react to the anti-corruption rallies, organized by Alexei Navalny, which took place in all the big cities? Were they shown on television? Maybe in passing. But everyone is connected to the internet, and there you can see how many people came out for them. The only thing you can show on television is what villains the Ukrainians are, what rascals there are in Syria, and talk shows where people applaud the politicians.”

The only thing the regions have common in terms of how local authorities have reacted to the strike are arrests. There have been several dozen arrests. After Bazhutin was detained and later released, three truckers in Dagestan were jailed for ten to fifteen days. According to reports shared by the strikers on the social networks, there have been further arrests in Surgut, Volgograd, Chita, and Ulan-Ude.

Speaking to strikers on April 4, Yakub Khujayev, Dagestan’s deputy transport minister, asked everyone to disperse for three months and give the government time to draft proposals for abolishing Plato. The strikers immediately booed Khujayev, grabbed the megaphone, and took turns speaking. They urged each other not to succumb to the regime’s blandishments.

“The sons of our officials ride around in Mercedes Geländewagen Td cars, but I can’t afford to buy a Lada 14. Why? Did God make them better than me? How are they better than me?”

“Take the highway patrol in Dagestan. What is the highway patrol? They’re just the highway patrol, but they act like generals. I find it ten times easier to talk to Russian highway patrolmen than with our non-Russian highway patrolmen. They’re quicker on the uptake.”

“Look, brothers, they surrounded us with troops and try to frighten us with weapons. Are we going to let them scare us this way?”

“No!”

Khujayev claims that Russian National Guardsmen did not encircle the truckers, as was reported by various media outlets.

“It was reported on a Friday that the riot cops had kettled the truckers. Every Friday, the mosques are packed to the gills with folks who park their cars on the road. Near the spot where the truckers have their camp, there is a federal highway, as well as a fork in the road and a mosque. Every Friday, law enforcement officers work to prevent a traffic jam. They go there and ask people not to park their cars on the road, and they help the highway patrol clear it. The exact same thing happened on the Friday when there was the outcry about the Russian National Guard.”

The strikers argue that Prime Minister Medvedev’s meeting with businessmen, at which truckers were present, allegedly, was a fake.

“When we found out who represented us at such a high level. It transpired that one of them was a United Russia party member who didn’t even own a truck, and the other guy travels the country telling everyone what a good system Plato is. How could they represent us if they didn’t even mention the strike at the meeting?” asks Timur Ramazanov, outraged.

Mobilization by Mobile Phone: How the Truckers Use Social Networks

During the strike, the truckers have cottoned to social networks accessible on smartphones, although previously most drivers had ordinary push-button mobile phones. The most popular mobile app is the Zello walkie-talkie app.* The OPR has its own channel on Zello, on which around 400 people are chatting at any one time. There are around 3,000 strikers signed onto the channel.

The app lets you use your smartphone like a walkie-talkie, albeit a walkie-talkie that operates through the internet. On the truckers’ channel, users not only share news from the regions, do rollcalls, and encourage each other but also advise each other about what to do in certain circumstances.

MAXMAX: Guys, under Article 31 of the Russian Federal Constitution, we have the right to assemble peaceably, but [the authorities] are citing Federal Law FZ-54 on rallies and demonstrations. I advise everyone to read it. All the details are there.

BRATUHA86: Guys, Surgut on the line. Vasily’s court hearing just ended. They charged him with holding an illegal assembly of activists and fined him 20,000 rubles [approx. 330 euros]. That’s how it goes. Tyumen, I heard it’s kicking off in your parts, too. They’re going to identify the most active strikers and fine them like Vasily.

VIRUSID: Fellows, let’s help out by crowdfunding the fine. Everyone chips in 100 rubles each. We’ll raise 20,000 in a jiffy.

ALEKSEYVADIMOVICH: Of course we’ll help out. There are over 300 users online right now and we’ll put the money together quickly.

KAMAZ222: Dagestan supports you. Tell me where to send the money.

1111: Fellows, what’s happening with you all in Dagestan? Is it true the riot cops want to put the squeeze on you? If that’s the way it is, I suggest humping it down there to support the guys.

FRTD: We could do that, but they won’t let us through if we drive in a convoy. We need to think about what to do without setting ourselves up.

Virtually no outside talk is permitted on the Zello channel. Anyone who is suspected of being a provocateur is immediately blocked. The strikers also use the social networks WhatsApp and Facebook.

“Within a year and a half, we have managed to rally an insane number of people around our flag. By and large, the alliance jelled on a professional basis,” says Bazhutin. “Communicating through social networks has really helped us. The guys even knew better than I did what was happened when I arrested. I didn’t know the police were going to release me, but they already knew.”

“Guys from other regions called me today. They had heard the riot cops in Dagestan were planning to disperse the strikers. They promised me that, if this were true, they would come and support them and prevent a clash,” says Mallamagomedov, echoing Bazhutin. “The strikers have been getting vigorous support from taxi drivers and van drivers. They don’t picket all day, but they show up often, bring us food and drinks, and give us pep talks. The talk on the social networks is that now they’re testing the system on large vehicles. Small-tonnage vehicles will be the next step, and then passenger vehicles.”

Digging Ditches and Dismantling Rails: Means of Combating the Strikers

The strike has been hindered not only by the arrests of activists. In one village, the authorities were especially creative. The truckers named the day when they would leave the village and head off to the strike camp. They would have to drive over a railway crossing to do this. In the morning, the eighteen-wheelers arrived at the crossing, and the drivers discovered the rails had been dismantled overnight, cutting off their only way out of the village.

In Rostov Region, the authorities dug a deep ditch around the parking lot where the strikers had gathered, referring to it as “emergency repairs.”

Mallamagomedov has been detained by law enforcement several times. In January 2016, Dagestan’s truckers met to discuss their common problems.

“We decided to establish our own association in the Republic of Dagestan. I was elected leader. After the meeting, I was put on the wanted list, although I wasn’t informed of this. On the Dagestan-Kalmykia border, I was forced to get off a bus and had to hitchhike home. Since then, I haven’t been able to visit Dagestan safely. I was placed on the list of extremists. When I call the police and tell them to take me off the list of extremists, because they know it’s not true, they promise they’ll take me off the list, but I’m still wanted.”

On April 5, Mallamagomedov was immediately picked up by police after a press conference in Moscow. Two men in plain clothes, who introduced themselves as criminal investigators, put Mallamagomedov in a car without plates and took him to an unknown destination. According to him, a case against him was cooked up in August 2016, when he was involved in a farmers’ tractor convoy in Rostov Region. The court order handed to Mallamagomedov on April 5 says he should have been jailed for ten days for an administrative offense, but he was released the evening of the same day. He doesn’t know why he was released, but says his attorney would be appealing to the court’s decision to sentence him to ten days in jail.

“My entire family—my two brothers and my father—are truckers,” says Mallamagomedov. “Several days ago, people came to my father’s house and demanded he sign a paper saying he would not be involved in the strike. ‘I undertake to attend all protests and rallies organized in support of the people,’ my father wrote on that paper.”

* On Monday, RBC reported that Russian federal communications and media watchdog Roskomnadzor would block the free walkie-talkie app Zello within twenty-four hours.

Translated by the Russian Reader