If you have been to Chronicles Bar [in downtown St. Petersburg], you have definitely seen the photos discussed in this film. In today’s session of “Screening the Real,” we are watching Leningrad 4, a documentary about Sergei Podgorkov and other champions of Leningrad’s unofficial photography scene during perestroika. Yuri Mikhailin spoke to the filmmaker, Dmitry Fetisov, about dramatic structure, time as a form and rhythm, and Soviet-era beer stalls.

My path to documentary filmmaking was a tortuous one. At school, I was interested in writing texts, and at the age of seventeen I decided to apply to the St. Petersburg State University of Film and Television (KiT) to study drama, but at the interview I was advised to go into documentary directing. At the time, Victor Kossakovsky was accepting students, but I didn’t go to study with him, I went to Tver (I’m from the Tver Region) and studied three years at the College of Culture, specializing in directing and theatrical acting. Then I went to study in Konstantin Lopushansky’s feature filmmaking program at KiT. I studied for a year, but them I decided to try my hand at documentary filmmaking again, although I didn’t really understand what it was.

I transferred to Vladislav Borisovich Vinogradov’s course, and I more or less made a go of it there. I guess I had found my master. It was the first time I saw examples of poetic documentary films with characters and dramatic structures that intrigued me. I also really liked Vladislav Borisovich’s work (I Return Your Portrait, A New Year at the End of the Century). I think that I have inherited to some extent his format, in which the films are based on interviews with the characters, and the themes have something to do with Leningrad culture.

My interest in photography stemmed from moving to St. Petersburg. I liked the texture of its central districts, the most banal things—palaces and , the difference between the Petrograd Side and Vasilievsky Island. And I was very interested in the movies made at Lenfilm Studios—Ilya Averbakh, the so-called Leningrad school, the perestroika-era pictures. This texture intrigued me. I came across the photographs of Boris Smelov, Leonid Bogdanov, and Boris Kudryakov. I became a big fan of theirs, and started looking for lesser-known photographers.

You could say that Leningrad 4 was born in 2011, when I went to a photo exhibition at the legendary Borey Gallery on Liteiny for the first time and saw Sergei Podgorkov’s work. I thought that I should make a movie about this man. I was very impressed by Ludmila Tabolina’s show at the Akhmatova Museum, as well as the exhibition on the Zerkalo photo club, from which many photographers had emerged.

In 2021, I decided to make a short film about Sergei Podgorkov. At the time, I had no idea that it would turn out to be a forty-minute movie. I wrote to Sergei on VKontakte, and he invited me to his place in Borovichi. If I were making the film now, I would probably add a video chronicle of the trip. Podgorkov showed us around the town, including the old railway station, and after filming we drank some good Novgorod moonshine with him to celebrate our acquaintance.

Many of the shots were made with Soviet gear—a Helios 40 telephoto lens. I bought it in a thrift store, and I successfully fitted this 1965-made lens to a Sony mirrorless camera. The Helios 40 handsomely blurs the edges and thus emphasizes the subject in the frame. It is my favorite lens.

After filming Podgorkov, I realized that the topic could be pursued further. I had always been interested in the Leningrad Rock Club, and so I decided to film Andrei “Willie” Usov, who was the staff photographer for the band Aquarium and did all the covers of their records, and was friends with Mike Naumenko.

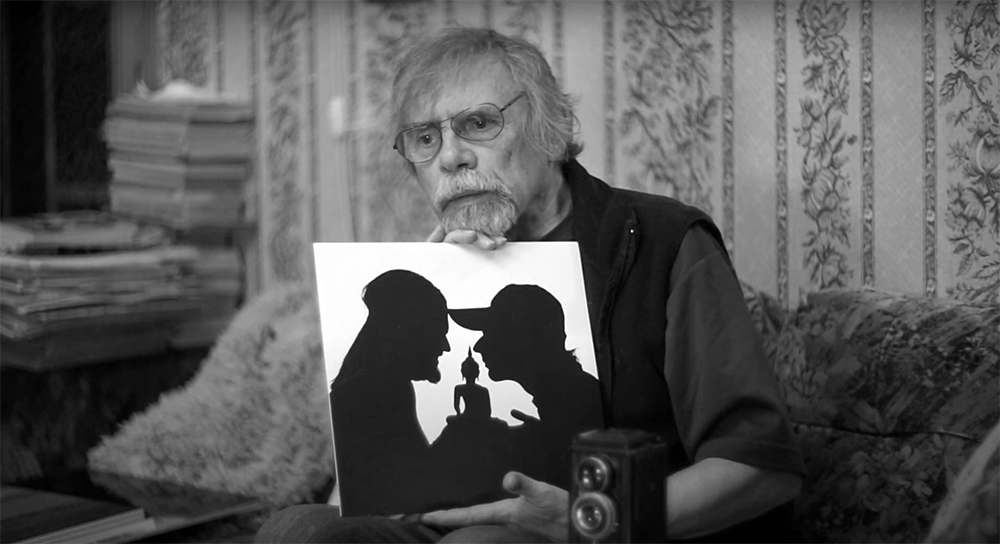

of Boris Grebenshchikov and Mike Naumenko. Still from “Leningrad 4,” Dmitry Fetisov, 2023

The third character was the pictorialist Ludmila Tabolina. I appreciate this movement in photography. The next character was Alexander Kitaev. I liked the Kitaev’s powerful countenance, that of a bohemian. Petersburg photographer, and I decided that I would film him even before I got acquainted with his images myself.

Another character is Valery Valran. He is not a photographer, but a well-known artist in Petersburg, a popularizer of photography, a curator of photo exhibitions, and the first to turn [photos by Leningrad’s underground photographers] into a photo album: the book Leningrad Photo Underground appears at the beginning of the film. I decided to include it in the film to tell about this photography movement a little from the outside.

And finally, there was Sergei Korolyov. I filmed him, but during editing I realized that, unfortunately, a short subject about him did not fit into the film. I edited it separately and posted it on my “Blog Stall” which I dreamed up when blogging was the cool thing and where I publish stories related to cinema. This episode is called “The Photographer Korolyov”.

How did I realize that these characters were enough? When I filmed them, I had an idea for the next film I might make: about photographers who are no longer alive, like Bogdanov and Kudryakov. And I decided that the filming was over.

The film took a long time to edit, almost a year. I realized that each photographer has a certain leitmotif. Sergei Podgorkov has a story connected with beer stalls (although he does not emphasize it himself), Andrei Usov has rock, Ludmila Tabolina has the white nights, and Kitaev has [Petersburg’s] Kolomna neighborhood.

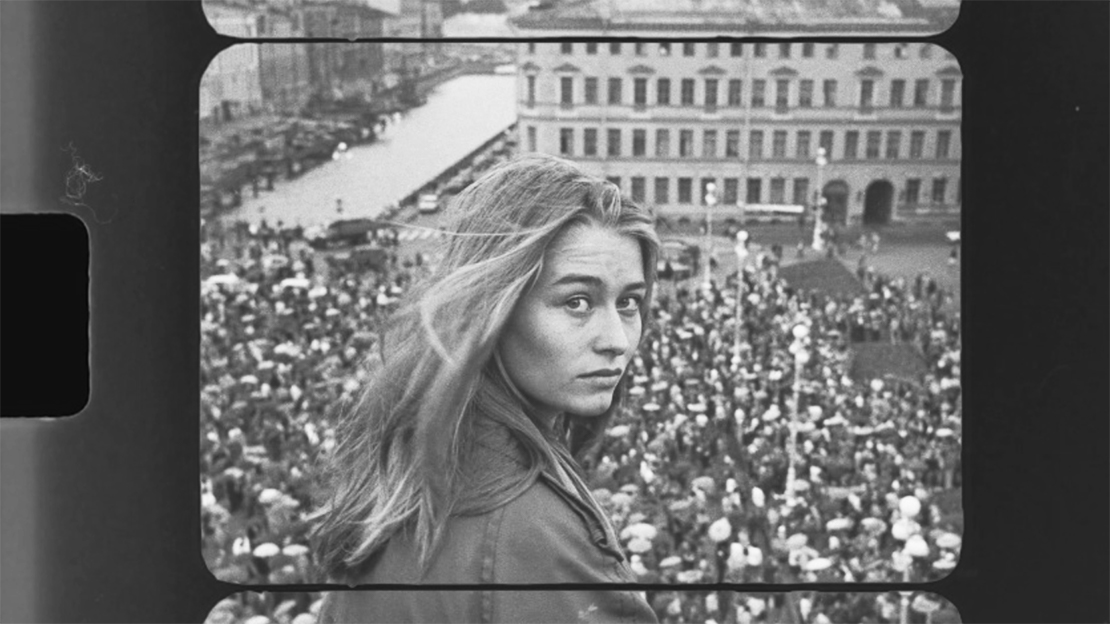

To separate the interviews and photos, I decided to use a film footage frame. Some of my colleagues think that this is visual bad form, but for me it seems logical: conversations with photographers are the present day, while their photos are the past, and the footage works as a transition between them.

Sometimes I wanted to connect the times. The chapter “Conversations at Beer Stalls” features music by contemporary jazz-noir artist Bebopovsky and the Orkestry Podyezdov. I had enjoyed him for a long time. I met the artist, and the opportunity to use his music in the film presented itself.

While I was editing, I did a photo shoot on black and white film for an acquaintance. I was supposed to make shots like in the scene in Godard’s movie Le petit soldat in which the main character takes a picture of a young woman. For this photo shoot, my friend bought a Leningrad 4 light meter on Avito. I realized that I would call the film that, because the main character is late Soviet Leningrad, and there are four photographers in it. Then I decided that I would divide the movie into four parts. Besides, perhaps these photographers possibly also used the Leningrad 4, as it was one of the most popular exposure meters of its time.

It was later that Sonia Minovskaya, my co-director and assistant on the movie, noticed that in some mythologies the nuumber four is the number of decay, death, and demised. And indeed, in each chapter something fades away or dies. In the first one, the Leningrad white nights are buried, while in the second, Mike Naumenko and a whole erа exits the stage. Then we see the end of the Summer Garden in its historical guise, and in the final chapter, where the rallies in the squares are shown, we see a country disintegrating. I didn’t think about this symbolism when I was making the film. I did it intuitively.

I understand that the editing is finished when a special, unique time emerges in a film. Time is a rhythmic form to me. A movie is ready to go when it suits me rhythmically. My films are calm, lyrical, and meditative. I probably like the documentaries of Wim Wenders for a reason.

Leningrad 4 was screened at the Arctic Open Festival in Arkhangelsk, where it got a super-warm reception; at the Salt of the Earth Festival in Samara; and in the online program at Artdocfest.

At one of the premiere screenings at the Rosphoto Museum, Sergei Podgorkov, with his usual irony, criticized the film for being too sentimental about an era that, in his opinion, is not worth the nostalgia. I did not put nostalgia in the movie, especially nostalgia for the Soviet Union, which I do not have. Andrei Usov noted that the films uses images from a time when the city was more interesting texturally for photographers. Nowadays, Petersburg is quite touristy, shiny and bright. He also admitted that the film left him with a heavy feeling. He and Naumenko had a great, strong friendship, and he still takes his departure quite personally.

Another character in the movie, Svetlana, attended the screening at the bar WÖD. In the final scene, we see a photo of her standing on the roof of a building opposite the Mariinsky Palace during the attempted coup in August 1991 and looking into the lens—as if that era were upon us today. This is a famous photo by Sergei Podgorkov. Recently, Sergei found Svetlana through the internet and invited her to the screening. And now, thirty-three years later, she saw herself on the screen and recounted how the picture was taken. Podgorkov had run out of film, but Svetlana was also an amateur photographer, so she lent him her own camera, and he photographed her.

Recently, I went to Chronicles Bar on Nekrasov Street and saw Podgorkov’s photos there. It was amazing. It is a young people’s bar, and yet the walls are adorned with photos of Soviet-era beer stalls, so it is as if two eras were connected through Podgorkov’s photographs.

Source: Yuri Mikhailin, “Screening the Real: Dmitry Fetisov’s ‘Leningrad 4,'” Seans, 25 May 2024. Translated by the Russian Reader