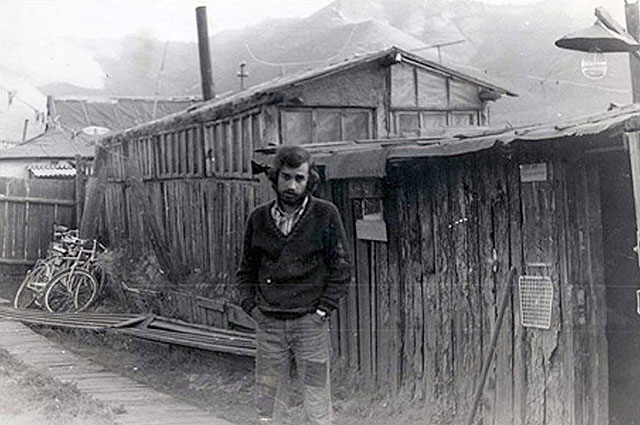

Alexander Podrabinek in exile in Yakutia in 1979. Courtesy of Institute of Modern Russia

Alexander Podrabinek in exile in Yakutia in 1979. Courtesy of Institute of Modern Russia

We Are Different

Alexander Podrabinek

Grani.ru

March 8, 2019

Nor are we in this together. I did not want to draw a dividing line between people and put them in different camps, but I have no choice: there are tough times on the way. If we are not lucky, things could go back to the way they were. You all will go back to your kitchens. Your tongues will be firmly in your cheeks again, and the jokes made by stage and TV performers will be cautious and carefully calibrated to register the authorized quantity of discontent. We will go back to our labor camps and prisons, our psychiatric hospitals and places of forced exile, to our intransigence and contempt for violence. By “we” I do not mean only those of us who have already spent time in those places. There will be new generations of stubborn, improvident, free-spirited Russians. We were different back then, and we are just as different now. Once upon a time, Solzhenitsyn quite accurately identified you as “smatterers.”*

You always knew what was permitted and what was forbidden. You had the Soviet individual’s sixth sense for knowing where the line ran. Few of you ever crossed the line, and the few who did left ordinary life behind forever, some going to the west, while others were sent east. When communism collapsed and freedom dawned, you immediately felt brave. You spoke loudly, angrily, and righteously. It was a sight to see. We were glad our ranks had swelled. We were glad we were stronger and could change our country.

The fresh breeze of change has subsided, however, and the familiar smell of Soviet rot is in the air. Censorship, political prisoners, extrajudicial killings, and wars of aggression have reemerged. Where are you now, masters of reincarnation? What side are you on? How many of you are still on our side? You now go regularly to the Kremlin to receive decorations, medals, state prizes, and honorary titles. You heed the demands of censorship and edit out anything that could cause Roskomnadzor to blow a fuse. You have a keenly honed sense of what can be said and what cannot be said, of what plays can be staged, movies made, and concerts held, and which it would be better not stage, make, and hold. You serve on a variety of presidential and ministerial councils. Pretending to be in opposition, you seek permission for your protests from the authorities, but as soon as the Kremlin calls, you rush there to explain yourselves and prove your personal indispensability.

As before, you sing the same old song about the value of small deeds, because you are afraid to be free. You were also afraid back then, when we were imprisoned. You carried the regime’s water in silence or grumbled under the watchful eye of art critics in plain clothes. You pretended to be fearless freethinkers and the movers and shakers behind imaginary reforms. On the stage, you cracked witty jokes approved by the censors. You published your censored stories and novels in the thick literary magazines. Commissioned by the State Committee for Cinema (Goskino), you made cheeky movies whose cheekiness was carefully calibrated. But you never crossed the line lest you lose your place on the gravy train.

You might wonder whom I am addressing. Who is the target of my reproaches and accusations? That is an easy question. Take an honest look at your past and your present. What did you do under socialism? What did you after it collapsed? Who made you bend your back in the old days? How straight do you stand up nowadays?

To be honest, the recent scandal involving humorist Mikhail Zhvanetsky compelled me to write this. Public outrage over the latest instance of a celebrity pandering to the Russian powers that be was countered by a chorus of defenders of spinal flexibility. How dare you? they asked. Who are you compared to him? He joked his whole life while you were silent. He is a genius, but you are nobodies. One defender dubbed the storm of criticism a “stink,” while another advised Zhvanetsky not to pay any mind to the “scum.” Yet another defender reminded everyone that Zhvanetsky was permitted to do what lesser people were forbidden.

It is amazing. Do you really regard yourselves as a magnificent, exceptional cultural elite? During the hardest times, you skillfully kowtowed to the Soviet regime. You were caricatured reflections of evil. You were witty, resourceful, and even gifted, but you were the regime’s shadow. You looked good amid a scorched desert where everyone was forbidden to do anything, but where you were allowed certain indulgences by royal decree. Is this what makes you so perpetually proud? Does it forgive you your past and future sins?

You are good at forgiving and vindicating yourselves. It is the meaning of your lives and the key to your survival. You have forgiven yourself for your cowardice during Soviet times, because the times were dangerous. You forgive yourself for selling out nowadays, because it is good for your wallet. You will always find a way to vindicate yourself. Proud, unperturbed, a noble air about you, you will walk the streets again.

Good luck at your old jobs!

* “The Smatterers” was the unhappy English coinage for the title and subject of Solzhenitsyn’s 1974 essay “Obrazovanshchina,” as published in the bilingual anthology From Under the Rubble.

Translated by the Russian Reader