Rusebo is Georgian for “Russians” in the vocative case. The word is chanted in Tbilisi by demonstrators protesting against the Georgian government’s draft law on “Transparency of Foreign Influence.” The draft law is called the “Russian law” because it is similar to the Russian law on so-called foreign agents, targeting organizations that receive funding from abroad.

In 2023, large-scale protests in Georgia stopped the law from being passed, but now the government is trying to pass it again in order, according to the opposition, to demonstrate loyalty to Russia and distance itself from the European Union.

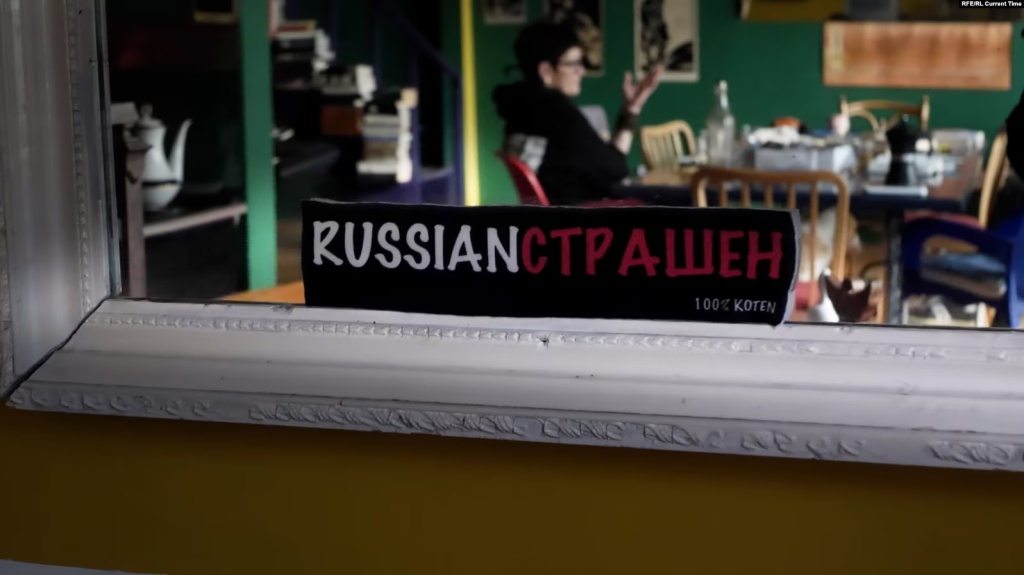

The chant rusebo! is directed at the police officers dispersing the protests and, more generally, at the Georgian authorities, which the opposition labels pro-Russian. However, the word rusebo is also taken personally by many Russian emigrants who fled to Georgia after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They include persecuted political activists, men fearing mobilization, and ordinary people who disagree with Putin’s politics. The attitude of Georgians toward them is wary and often outright negative, simply because they are from Russia. As one of the emigrants puts it, “Tough people, they resist, I wish they could be like that in Russia too. But I also feel a little bit on the other side. They shout rusebo—that’s literally me.”

Russian emigrants amidst the protests in Georgia is the subject of Rusebo!, a film by Yulia Vishnevetskaya.

(2024; in Russian, English and Georgian; no subtitles)

An argument between a Georgian activist and a Russian emigrant

— I was walking down the street, and a Russian was walking towards me. I didn’t know whether tomorrow he would change into a Russian uniform and shoot at me. The people who have no money but who had the opportunity to settle down here in some way I understand very well. But those who could go anywhere in the world because they had money, why did they come here too? They eat khinkali, it’s all they talk about. They post pictures on Facebook of themselves swanning around here, but I don’t understand why they left Russia. Just to tag along?

— Would you just leave your home like that and run away?

— No. The only thing I do know is that running away won’t change anything.

— You think you can change anything by not running away?

— Well, they’d be put in prison.

— So, it’s okay to “emigrate” to a place where people are raped with mops? Wouldn’t that scare you?

— I understand perfectly well. I feel sorry for the people who had to leave their homes, their beloved dachas, and so on. But it doesn’t change my attitude at all. I would not have run off to any country. Maybe I would have sent my son away so that he would not be mobilized, but I would have stayed and continued to fight.

— Do you hold it against us that we ran away?

— Navalny was not afraid: he went back and did the right thing, despite everything that happened afterwards. I respected him after he came back: he knew that he would be imprisoned and killed, but he went back anyway. I’m not encouraging anyone to go back and die in prison, but the man did the right thing. That’s what justified him in my eyes.

— I care more about a living person than symbolic ones….

— A living person who can’t do anything?

— Yes, as opposed to a dead man who wanted to do something. I’m not willing to pay with lives.

— And I’m willing to pay with my life for my freedom.

— You don’t understand how infuriating it is. When you realize that there is Putin, who is ten times stronger than you, who can do anything to you, when people you respect, whom you know perfectly well, are in prison, dying there, and then you come to Georgia and are told, “You are trying badly, we want you to win, but you somehow don’t want it badly enough.” I just don’t understand how you can seriously say this. I am quite offended that you say it.

— You occupied twenty percent of Georgia, your country occupied us.

— I am not responsible for my country.

— But we are responsible for our country, that’s the difference. Why do you take offense at me for complaining? You’ve been letting it happen for three hundred years—all of you, there are many of you and not enough of us. And for three hundred years you’ve been allowing it to happen and occupying us. You speak for everyone now. We have a shitty government, we’ve been sitting in shit for twelve years and we’re fighting our government. Take offense at your fellow Russians, not at me. I’m not at war with you, I’m at war with our regime and your regime. Everything was taken away from us, they took away the place where I had been going since I was a child. I cried, I stood and sobbed, there were Russians standing there with machine guns. And this is my life, this is how we have been living for so many years.

— Everything was taken away from us too, can you understand that?

— No, I can’t. Nothing was taken from you. Did you have a protest rally when we were bombed in 2008, when they took away more Georgian territory? This building shook because a bomb was dropped nearby. I walked around for three months, looking up at the sky to see if any airplanes were flying by. It was a fright. So I understand Ukrainians perfectly well. We will win.

— No.

— Why won’t we win?

— Because you’re outnumbered.

— We are few but we are strong.

— It is just important that there is a moment when you have to start believing.

Monologues of Georgians and Russians

— I had a friend from Russia. We would meet at international conferences. He was a young Russian, very interesting, very fond of Georgia and Georgians. We became friends, and one day, right after the war in 2008, he and I met. He hadn’t written anything to me during the war, which seemed crazy to me. He never once asked how we were doing. And so we met, and I expected him to say something, but he didn’t say anything. So I told him I was very upset about it. And he said, “Oh, come on! Did those few little firecrackers make you scared?” That reinforced my feelings about Russia. If an ordinary, normal, good Russian has these feelings about a war that was terrible, that took people’s lives and people’s homes and divided their lands, and says, “You were scared of a couple of firecrackers,” I thought that it must be true that everyone in Russia thinks that way. Before 2008, my university friends still went to Russia to get their residency training. But if someone went after 2008, everyone said, “What? What are you doing?” That was really a turning point.

I was anti-Russian from the age of eight when I learned that members of my family had been murdered in a single night in 1924. My parents joined the anti-Soviet movement in the 1980s. In 2008, some of my friends went off to fight against the Russians. We have a lot of reasons to hold grudges. But I think this war, which brought so many anti-Putin Russians to Georgia, has shown a different side of Russia. I thought, Okay, these people can bring us know-how and knowledge of how to fight Putin. They came here to survive. I see Russians in Tbilisi, some of them have even opened their own establishments on my street, and if the fact that I buy a cup of coffee from them will help defeat Putin, and if they are here without guns, not killing Ukrainians, then I support that.

— I lived most of my life in Nizhny Novgorod, but the last ten years I lived in Petersburg. I was a carpenter, a joiner: I built ships and did all sorts of renovations. I was involved in the anarchist, anti-fascist and environmentalist movements. Then it all became about helping political prisoners. The rumors that the borders would be closed was the last straw: I realized that I had to move while I had the chance. I hoped that the regime would not withstand such a thing, that there would be mass strikes and so on. No way.

The unemployment here [in Georgia] is serious, of course. There is little purchasing power. The rates for all work are lower than in Russia. While an IT guy can tuck his laptop under his arm and throw everything he has into crypto, I have a workshop and machines. I’m not a little boy anymore: you’ll break down drilling all your life. You can’t go back. If you’ve made that choice, go on pivoting as you wish.

With its values—its love of freedom, love of nature, love of history, and love of human rights—Georgia has everything I need, except that “I am part of the power which forever wills good and forever works evil.”* Georgians have the sense that there is a mighty power on their doorstep and that it is hostile. Accordingly, you can be seen as part of this danger, even amongst those Georgians who are friendly to Russians. I have local friends here who treat me normally: there is nothing imperialist about you, they say to me. But you can’t expect to fit in in a country that has been experiencing Russian aggression essentially nonstop for better or worse since it gained independence. Some Russians intend to stay here, but I don’t think it will be particularly possible.

But we should support the people protesting for their freedom if only out of gratitude to this country that they put up with us here. Anarchists basically have this principle: we are always on the side of the oppressed and against the oppressors. I do not wish any country to suffer the same fate as Russia. I do not want the same idiotic regime to be established here. No one has any use for it, neither the Georgians nor us.

* An inversion of the quotation from Goethe’s Faust that serves as the epigraph to Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita: “I am part of the power which forever wills evil and forever works good.”

Source: “A life for freedom’: Russian emigrants amidst the protests in Georgia,” Radio Svoboda, 12 May 2024. Translated by the Russian Reader. The film also features a former auditor from Rostov who moved to Tbilisi after the war started and now works as a cleaner, but her monologue wasn’t included in this online article. I have translated the Georgian doctor’s monologue as reproduced here in Russian, although her original remarks, made in English, are nearly entirely audible through the Russian overdub.

Discover more from The Russian Reader

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.