Rewriting Sandarmokh

Who Is Trying to Alter the History of Mass Executions and Burials in Karelia, and Why

Anna Yarovaya

7X7

December 13, 2017

The memorial cemetery with the mystical name Sandarmokh. The word has no clear meaning or translation: there are only hypotheses about its origin. But Sandarmokh definitely evokes associations with executions, suffering, and history. Many people are horrified by the place due to what happened there eighty years ago. The site of mass executions of political prisoners, a place where over seven thousand murdered people are buried in 236 mass graves, Sandarmokh is the final resting place of those whose odyssey through the concentration camps in 1937 and 1938 ended with a bullet in the back of the head.

Since 1997, when the cemetery was discovered, Sandarmokh has come to be a nearly sacred site for descendants of the victims, local residents, historians, and social activists. Since then, Sandarmokh has hosted an annual Remembrance Day for Victims of the Great Terror of 1937–1938, an event attended by delegations from various parts of Russia and other countries.

Nearly twenty years later, historians in Petrozavodsk have claimed that, aside from the executions of the 1930s, Soviet POWs could also have been killed and buried there during the Second World War. The hypothesis has provoked much discussion in the academic community, and attracted the attention of the Russian and Finnish media. People who deal with the subject professionally—historians, activists, and scouts who search for bodies of missing servicemen and war relics—are at a loss. What new documents have come to light? Where can they see the declassified papers? The people behind the sensation have been in no hurry to publish documents, thus heating up the circumstances surrounding Sandarmokh.

What are the grounds for the hypothesis that Soviet POWs were shot at Sandarmokh? Who has been pushing the conjectures and why? This is the subject of Anna Yarovaya’s special investigative report for 7х7.

___________________________

Yuri Dmitriev: A Year in Pretrial Detention

There were only three court bailiffs last time. Sometimes, there have been five, sometimes, as many as ten. The number is always at the discretion of Judge Maria Nosova. The number of bailiff she orders is the number that are dispatched to the courtroom. Even when there are three bailiffs, Yuri Dmitriev, the short, thin leader of Memorial’s Karelian branch, now shaven nearly bald, is barely visible behind their broad shoulders. So, the best place to observe the procession is the little balcony on the third-floor staircase at Petrozavodsk City Courthouse. Knowing that people are waiting for him at the top, Dmitriev climbs the stairs with his head thrown back. He looks for his daughter Katerina, almost always picking her out of the crowd. Of course, she does not always appear on the staircase, because there are always lots of people who want to chat with her, inquire about her father’s health, and find out the latest news from the pretrial detention center, while there are only two people allowed to meet with Dmitriev: Katerina and his defense counsel Viktor Anufriyev. The latter is too businesslike to approach with questions about his client’s personal life.

A group of supporters has lined the walls of the corridor outside the courtroom. Last time, the support group was especially large. It included young students from the Moscow International Film School, old friends of Dmitriev’s and colleagues from Memorial, most of them out-of-towners, ordinary sympathizers (including such extraordinary people as famous Russian novelist Ludmila Ulitskaya), local, national, and foreign reporters, and Petrozavodsk activists.

The support group outside the courtroom is always impressive. Photo courtesy of 7X7

The support group outside the courtroom is always impressive. Photo courtesy of 7X7

“Four men in the cell. Normal treatment. Yes, he has a TV set. But TV is making Dad dumb. Russia 24 and the like are constantly turned on, and there is nowhere to hide from it,” Katerina relates to someone after the applause from the support group fades.

The trial is being held in camera: no one is admitted into the courtroom. Last time, the judge did not allow a staffer from the office of the human rights ombudsman into the courtroom, although a letter had been sent in advance requesting she be admitted. But people come to the hearings anyway, and they travel from other cities. They come to see Dmitriev twice (when he is led into the courtroom and when he is led out), chat with Katerina, and make trips to the two memorials to victims of the Great Terror that Dmtriev was involved in opening, Krasny Bor and Sandarmokh. Many people are certain that Dmitriev has been jailed because of Sandarmokh.

Bykivnia, Katyn, Kurapaty. Next Station: Sandarmokh

Many people see Dmitriev’s arrest and subsequent trial not as an outcome, but as the latest phase in a war not only against him but also against “foreign agents” in general and Memorial in particular. Until recently, the laws have been made harsher, the Justice Ministry has been pursuing “foreign agents” vigorously, and state media have been attacking “undesirables.” More serious means have now come into play. The “justice machine” has been set in motion in the broadest sense, including investigative bodies and the courts.

A year before Dmitriev’s arrest

The Memorial Research and Information Center in St. Petersburg was designated a “foreign agent.” In 2013, the status of “foreign agent” had been awarded to another Memorial affiliate, the Memorial Human Rights Center in Moscow. The International Memorial Society was placed on the “foreign agents” lists in October 2016, two months before Dmitriev’s arrest.

Six months before Dmitriev’s arrest

In early July 2016, the Finnish newspaper Kaleva published an article by a Petrozavodsk-based historian, Yuri Kilin, entitled “Iso osa sotavangeista kuoli jatkosodan leireillä” (“Most POWs Died in Camps during the Continuation War”).* The article is a compilation of findings by Finnish researchers, spiced up with the Kilin’s claims that Finnish historians, poorly informed about certain aspects of military history, had no clue Sandarmokh could have been the burial site of Soviet POWs who were held in Finnish camps in the Medvezhyegorsk area.

There is not even a casual mention of Memorial in Kilin’s article. However, the article “Memorial’s Findings on Repressions in Karelia Could Be Revised,” published two weeks later on the website of Russian national newspaper Izvestia, featured the organization’s name in its headline. And an article on the website of the TV channel Zvezda, hamfistedly entitled “The Second Truth about the Sandarmokh Concentration Camp: How the Finns Tortured Thousands of Our Soldiers,” not only summarized Kilin’s article but also identified the supposed number of victims of Finnish POW camps, allegedly buried at Sandarmokh: “thousands.” The article also featured images of scanned declassified documents, “provided to the channel by the Russian FSB,” documents meant to confirm Kilin’s hypothesis. They did not confirm it, in fact, but we will discuss this, below.

Somewhere in the middle of the Zvezda article, the author mentions in passing, as it were, that since Kilin’s article had been published in a Finnish newspaper “before the archives were declassified,” the “long arm of state security is irrelevant in this case.” Indeed, what could state security have to do with it? Professor Kilin merely voiced a conjecture, and supporting classified documents were then found in the FSB’s archives and immediately declassified. It could only be a coincidence. True, at some point, Sergei Verigin, director of the Institute for History, Political Science, and the Social Sciences, and Kilin’s colleague at Petrozavodsk State University, tried to explain to journalists that Kilin had been working in the FSB archives at the same time as Verigin himself (“independently from each other”). It was there Kilin found the relevant documents and studied them thoroughly. So, the story that Kilin had anticipated the FSB’s discovery holds no water. Why the FSB had handed over documents, documents confirming nothing, to Zvezda remains a mystery. Maybe so no one would get any funny ideas about the “long arm of state security.”

Another mystery is why Verigin decided to distract the attention of journalists and readers from the topic of alleged Finnish war crimes and focus it on Memorial.

“Memorial was not interested in the possibility that Soviet POWs could be in the shooting pits [at Sandarmokh],” the historian told Izvestia‘s reporter.

Five months before Dmitriev’s arrest

A month after Kilin’s article was published in Kaleva, on August 5, 2016, the annual events commemorating the victims of the Great Terror took place at Sandarmokh. For the first time in the nineteen years since the memorial had been unveiled, the authorities did not participated in the memorial ceremony: neither the Karelian government nor the Medvezhyegorsk District council sent anyone to the event. Some officials later admitted they had been issued an order from their superiors not to take part in Memorial’s events at Sandarmokh.

In September 2016, Sergei Verigin spoke at a conference in Vyborg, at which he first presented his theory about the mass burials at Sandarmokh. The conference proceedings were published in a collection that included an article by Verigin. The article cites documents from the FSB Central Archives, the same documents that had been scanned and published on Zvezda’s website.

Three weeks after Dmitriev’s arrest

Yuri Dmitriev was arrested on December 13, 2016, six months after Kilin’s incendiary article in theFinnish newspaper. Three weeks after his arrest, Rossiya 24 TV channel aired a long exposé on Memorial whose takeaway message was that an organization already identified as a “foreign agent” employed rather dubious people who had an appetite for child pornography. In keeping with the spirit of the “long arm of state security is irrelevant in this case,” the exposé featured photographs, allegedly from Dmitriev’s case file, unmasking the immorality of Memorial employees.

Six months after Dmitriev’s arrest

The assault on Sandarmokh began in earnest in June 2017, when Petrozavodsk State University’s fanciest and most well-equipped conference hall hosted a round table entitled “New Documents about Soviet POWs in the Medvezhyegorsk District during the Finnish Occupation (1941–1944).” The round table’s organizers, historians Yuri Kilin and Sergei Verigin, expounded their theory about the mysterious murders of Soviet POWs in Finnish prison camps in the Medvezyegorsk area. The scholars were certain that the murdered men, who might have numbered in the thousands, could have been buried in Sandarmokh.

However, like the author of the article on Zvezda’s website, who could not help but insert the phrase about the “long arm of state security,” Professor Verigin also made an involuntary slip of the tongue.

“We do not in any way cast doubt on the fact that Sandarmokh is a site where political prisoners are buried. There were executions and mass burials there. We admit that. But we argue that our POWs could be buried there as well. It’s like in Katyn. First, the NKVD carried out executions there, and then the Germans did. In the same place. And the burials were in the same place.”

___________________________

FYI

The Germans did not shoot anyone in Katyn: the NKVD did all the shooting there. The Germans shot or, rather, burned people in Khatyn and a hundred villages in the vicinity. The confusion between Katyn and Khatyn, to which military historian Sergei Verigin has also fallen victim, is commonly regarded as a ruse devised by Soviet propaganda to confuse the hoi polloi. A memorial was erected in Khatyn, whereas Soviet authorities tried for many years to hide what had happened in Katyn. People at Memorial now have no doubt that authorities are trying to pull off the trick they once did with Katyn with Sandarmokh: water down the history evoked by the name, cast a shadow on the memorial as a place of historical memory associated with the Great Terror, and confuse people, not so much present generations as future generations.

___________________________

Memorial, whose staffers and members are Russia’s foremost specialists on political crackdowns and purges, were not invited to the round table. The same day the round table on Sandarmokh was held in Petrozavodsk, Memorial was holding a press briefing on the Dmitriev case in Moscow. Sandarmokh was also recalled at the press briefing as well, and historical parallels were drawn.

“That way of framing the issues smacks heavily of Soviet times. When the burial pits were found at Katyn, outside Smolensk, the Soviet authorities palmed the atrocity off on the Germans to the point of introducing it as evidence at the Nuremberg Trials. When the site at Bykivnia, outside Kiev, was found, the Soviet authorities claimed there had been a German POW camp nearby, that it was the Germans who did it. When the site at Kurapaty, near Minsk, was found, the Soviet authorities also tried to shift the blame on the Germans. Now we see the same thing at Sandarmokh, with the Finns standing in for the Germans. This innuendo about Sandarmokh is not new,” said Anatoly Razumov, archaeologist and head of the Returned Names Center at the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg.

The organizers of the Petrozavodsk round table have established an international working group whose objective is not only gathering and discussing new information about Sandarmokh but also performing new excavations at the memorial to search for the alleged graves of Soviet POWs. Three months after the round table, Sergei Verigin gave me a detailed account of this undertaking, as well as the documents he has found.

Sergei Verigin: We Are Merely Voicing an Opinion

Sergei Verigin, director of the Institute for History, Political Science, and the Social Sciences

Sergei Verigin, director of the Institute for History, Political Science, and the Social Sciences

Historian Sergei Verigin, who was quoted by Izvestia saying new documents had been uncovered in the FSB archives and claimed that Memorial had ignored the issue of whether Soviet POWs were possibly buried at Sandarmokh, agreed to an interview almost gladly and invited me into his office.

He regaled me at length about his long career as a military historian: he has published a number of papers and books based on declassified FSB archival documents. His books, which had been published in Finnish several years ago, were still sold in Finnish bookstores alongside works by Finnish military historians, he said.

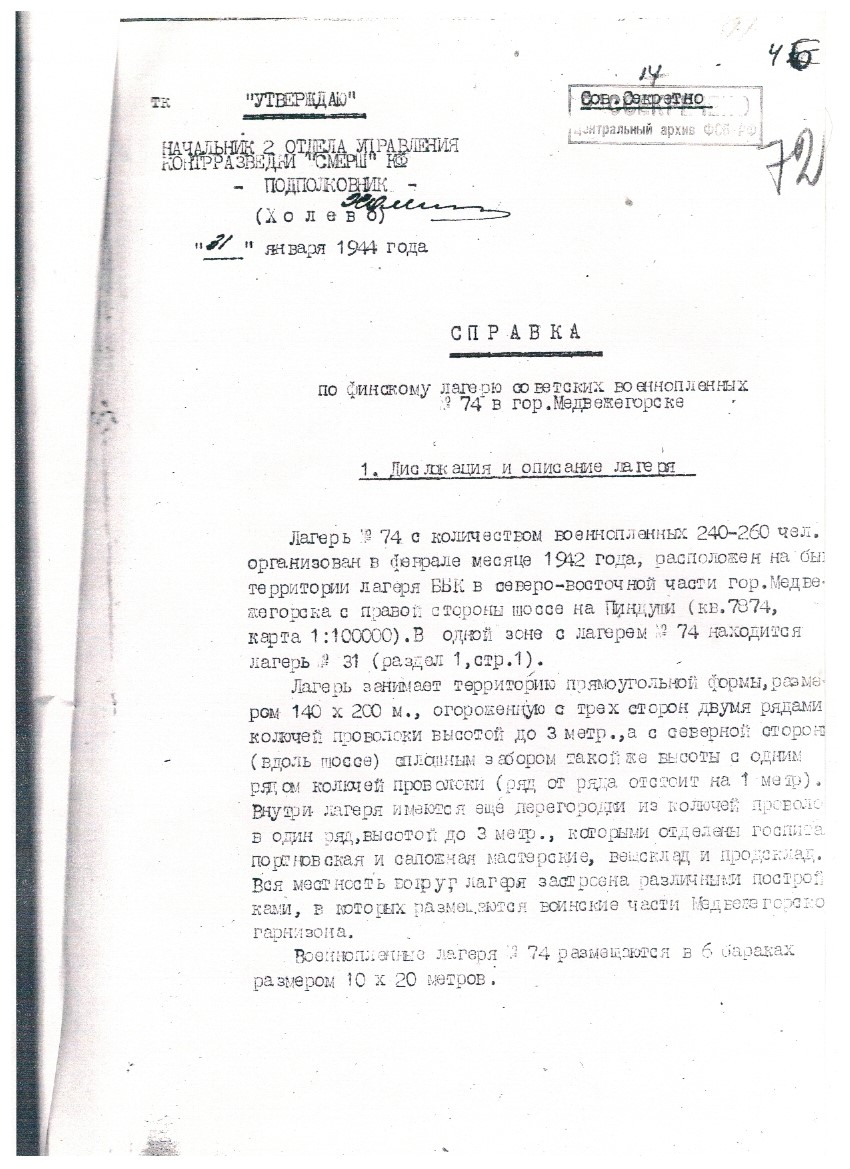

He began studying the new documents, containing information gathered by the military counterintelligence agency SMERSH from 1942 to 1944, in the archives of the Karelian FSB, immediately after they were declassified. Apparently, it was Verigin who uncovered the evidence that, according to him and his colleague Yuri Kilin, pointed to Sandarmokh as a site where Soviet POWs were buried. During our interview, Verigin was much more cautious with numbers, preferring to speak of “dozens and hundreds” of prisoners who had been shot.

“According to our evidence, hundreds of men were killed. The area was near the front lines, a place where civilians had no access, and you could bury people without being noticed. The Finns did not flaunt what they did. More POWs died from hunger, disease, and torture than from executions. Why have we concluded that POWs could have been buried at Sandarmokh? Because the Finns used the infrastructure that had existed in the NKVD’s prison camps. The documents even contain the names of several people who were imprisoned in NKVD camps, released, drafted into the Soviet army, captured by the Finns, and imprisoned in the exact same camps. Why have we voiced this hypothesis? Because the camps were large. There were six camps, containing thousands of people. Hundreds of people died of hunger, cold, and torture. But where are the graves? Clearly, a few could have been buried in the city, but where were dozens and hundreds of men buried?”

“Can these numbers, i.e., the ‘hundreds’ of men buried, be found in the documents you uncovered?”

“The numbers are there, but the burial site isn’t. That’s why I am asking the question. I am currently wrapping up an article entitled ‘Are There Soviet Prisoners of War in the Shooting Pits at Sandarmokh?’ The article contains lists, names, numbers. It names outright the names of the men who were shot.”

One of the arguments bolstering the hypothesis that many Soviet POWs probably perished is that Soviet POWs worked on building the Finnish fortifications near Medvezhyegorsk, since the Finns lacked their own manpower. What happened to these prisoners? The hypothesis is that they were shot. Verigin does not believe the Finns took Russian POW workers with them when they retreated. Under the agreement between Finland and the Soviet Union, mutual prisoner exchanges were carried out. Among the soldiers who were sent back to the Soviet Union, Verigin claims, not a single former POW who worked in Medvezhyegorsk has been discovered.

“I’m not casting a shadow on the burials of political prisoners. Sandarmokh is indeed a central burial site of victims of the Stalinist terror, of the political crackdown of the late 1930s, one of the largest in northern Russia. We have simply voiced the opinion that our POWs could be buried in these graves. We simply have to perform excavations. If we confirm the hypothesis, we will erect a monument to our POWs in the same place where monuments to Terror victims now stand.”

When discussing the work that must be done, Verigin returned to a familiar idea: a working group that included not only Russian scholars but also Finnish and German researchers must be established. (The Germans built POW camps in northern Karelia.) Verigin suggested that members of grassroots organizations, members of the Russian Military History Society, scouts who search for WWII relics and bodies, e.g., Alexander Osiyev, chair of the Karelian Union of Scouts, Sergei Koltyrin, director of the Medvezhyegorsk Museum, and basically everyone who disagreed with the hypothesis or was skeptical about it should be invited to join the working group.

“We are open. We invite everyone to join us. Maybe we won’t prove our hypothesis or maybe we’ll find another burial site. You can understand people: the notion that Sandarmokh is a place where victims of the political purges were shot is an established opinion, and they find it hard to get their heads around the idea there might be Soviet POWs there. The problem with Sandarmokh, you know, is that only five of the 230 graves there have been disinterred. Subsequently, the prosecutor’s office imposed a ban, and currently it is a memorial complex where all excavation has been prohibited. But if we establish an [international] group and argue [our hypothesis] convincingly, perhaps we will be allowed to carry out excavations with scouts and see whether there are POWs there or not. There are telltale clues: the dog tags of POWs and so on. If we could find such clues, we could carry out an exploratory dig there. We would be able to prove or not prove our hypothesis, but the hypothesis exists. The main idea is to pay tribute to the men who died in Finnish concentration camps during the Great Fatherland War [WWII] and erect a memorial of some kind. Because as long we don’t find a single [burial] site, there will be no monument to our POWs.”

Remembrance Day at Sandarmokh, August 5, 2017

Sandarmokh Shmandarmokh, or a Tribute to Perished POWS?

Have the historians from Petrozavodsk State University uncovered or comme into possession of documents testifying to the mass shootings and burials of Soviet POWs in the vicinity of Medvezhyegorsk? What other pros and cons can be advanced for and against the hypothesis? My search for the answers took nearly six months. During this time, I was able to examine the declassified documents myself and conduct a dozen interviews, in person and on the web, in Russia and Finland, with people who have researched Sandarmokh and the political purges, as well as the war and prisoners of war.

I was unable to find either direct or indirect evidence that the Finns engaged in large-scale executions and burials of Soviet POWs near Medvezhyegorsk. This account or, as the Petrozavodsk-based historians say, hypothesis, could not be corroborated either by the archival documents and published matter I studied nor by the specialists I interviewed.

Some of Kilin and Verigin’s historian colleagues flatly, even irritatedly refused to commment on their hypothesis for this article. According to one such historian, serious researchers would not take the accounts of escaped Soviet POWs and Finnish saboteurs, as provided to SMERSH, at face value as sources, as did the editors of a book about the “monstrous atrocities,” allegedly committed by the Finns in Karelia, which I discuss, below. Such sources should be treated critically.

“Issues like this have to be discussed in person, at serious academic conferences, with the documents in hands\, and not by leaking articles to the media,” said a researcher who wished to remain nameless.

Most of the specialists we interviewed were happy to speak on the record, however.

Sandarmokh Discoverers Irina Flige and Vyacheslav Kashtanov: It’s Out of the Question

The Dmitriev trial has generated a lot of buzz. Journalists writing about the case have underscored the significance of Dmitriev’s work as a historian and archaeologist, the fact that he discovered Sandarmokh, was involved in establishing the memorial at Krasny Bor, and worked on excavations on the White Sea-Baltic Canal and the Solovki Islands. Dmitriev usually did not not work alone, however, but in large and small teams of like-minded people and often, which was not surprising at the time, with support from enthusiasts in the regional government and local councils. In the 1990s, secret service officers also often assisted in the search for victims of the Terror.

Irina Flige and Vyacheslav Kashtanov were involved in the expedition during which the shooting pits of Sandarmokh were unearthed. Director of the Memorial Research and Information Center in Petersburg, Flige went to Karelia in the summer of 1997 to work in the archives of the local FSB, where she met Dmitriev. At the time, Kashtanov was deputy head of the Medvezhyegorsk District Council and provided Dmitriev and Flige’s expedition with organizational support. He asked the local army garrison to lend them troops to dig in the spots where Dmitriev and Flige asked them to dig.

Flige emphasized the archival documents relating to Sandarmokh have been thoroughly examined on more than one occasion. She argued there could be no doubt the place was the site of mass executions during the Great Terror. The approximate number of those executed has been documented as well. Dmitriev has compiled a list of the surnames of those executed: there are over 6,200 names on the list.

Flige was reluctant to discuss new hypotheses about the executions in the Medvezhyegorsk District. According to her, superfluous mentions of the conjectures there could have been other executions at Sandarmokh played into the hands of Kilin and Verigin.

“They provide no documents, so we cannot refute them. If they provide documents, they can be studied and refuted, but denying the existence of documents is beneath one’s dignity. The only possible stance at the moment is to demand the documents be made public. Otherwise, this is a publicity stunt meant to downgrade Sandarmokh’s worth. It’s unproductive to demand evidence from them and discuss the question before they do so,” said Flige.

According to Flige, there is no possibility of getting permission to perform excavations on the premises of the memorial complex, which is what the Petrozavodsk-based historians want to do. More serious grounds are needed to justify the excavations than the hypotheses of two men, even if the two men are academic historians.

___________________________

Irina Flige on the Search for Sandarmokh

We kept working on the case file under conditions in which we had to examine the documents [along with FSB employees], and they would permit us to make photocopies only of excerpts, of quotations from the case file, which was malarkey. In the next interrogation transcript, Matveyev [?] recounts that his apprehensions were not groundless, since once a truck had broken down near a settlement, a kilometer outside of Pindushi [in the Medvezhyegorsk District]. He then tells how afraid he was he had so many people in the truck, who knew where they were being taken, and he was stuck near a village and worried they would be found out. We thus located the second point, Pindushi.

___________________________

Vyacheslav Kashtanov, who even now organizes people for volunteer workdays at Sandarmokh, is confident that no one except victims of the Great Terror lie in the execution pits there. Kashtanov has not only document proof that executions took place at Sandarmokh but eyewitness testimony as well.

“The Yermolovich family has done a great deal of work on Sandarmokh. Nikolai Yermolovich was editor of the Medvezhyegorsk newspaper Vperyod. He claimed to have spoken with an eyewitness who had been inside the restricted area where the executions occurred. Periodically, the old Povenets road [which passed near the memorial complex] would be closed, and gunshots would be heard in the woods. What we found in the shooting pits themselves, when we unearthed them, was quite recognizable: bodies that had been stripped of clothes and shoes, with typical bullet wounds [to the back of the head].”

Kashtanov is no mere district council employee. He was educated as a historian, and by coincidence, Sergei Verigin was his university classmate. Verigin’s account of executions and burials during the Second World War had come as news to Kashtanov. He admitted that individual Soviet POWs had been executed, but he could not believe mass executions had taken place. When they had visited Medvezhyegorsk, Kashtanov had spoken with Finns about the war and Finnish POW camps, and there was mention of such possibilities during their frank discussions.

“It’s out of the question!” said Kashtanov. “If you examine the layout of the camps, it could not have been a matter of thousands of soldiers executed, because several hundred men were housed there. If we look at the pits [at Sandarmokh], we see they are staggered. This is also evidence of the homogeneity of the executions. Of course, individual executions could have been carried out anywhere. But transporting thousands of people [to Sandarmokh] would have involved unjustifiable risks and costs.”

Kashtanov believes the whole story belittles not only Sandarmokh but also those people who were shot there.

Volunteer workday at Sandarmokh. Photo by Sergei Koltyrin

“Maybe They Want a Sensation?”: The Arguments of Scouts, Local History Buffs, and Historians

Alexander Osiyev, chair of the Karelian Union of Scouts, came to be interested in the topic of executions of POWs at Sandarmokh almost accidentally. He was involved in the round table at Petrograd State University in June. He showed the audience maps of the front lines and tried to persuade them no executions could have taken place at Sandarmokh during the war. Sergei Verigin rudely interrupted him, saying the scout did not have enough evidence. Osiyev did not give up on the idea, gathering that selfsame evidence in Karelia’s archives.

According to Osiyev, the hypothesis advanced by the university scholars had several weak points, and those weak points were underscored by the very same documents to which they referred. After carefully reading the interrogation transcriptions of former POWs from Camps No. 74 and 31, as cited by Kilin and Verigin, Osiyev concluded the prisoners could not have served in the battalions that built fortifications in the Medvezhyegorsk District.

“If you compare the descriptions of the POWs with the photographs of the people who built the fortifications, as preserved in the Finnish Military Archive, things don’t add up. A man wearing a hat and a cloak of some kind bears no resemblance to the description of POWs in the interrogation transcripts.”

Builders of fortifications in the Medvezhyegorsk District. Photo courtesy of SA-Kuva Archive and 7X7

Builders of fortifications in the Medvezhyegorsk District. Photo courtesy of SA-Kuva Archive and 7X7

In the above-mentioned transcripts, former inmates of Finnish POW camps who had been arrested by the Soviet authorities described in detail the outward appearance of Russian POWs in the camps of Medvezhyegorsk.

“What kind of clothing and shoes did the prisoners of have?”

“The prisoners mostly wore English overcoats and Finnish trousers and army tunics. In the summer, they went barefoot, but from September 1 they were issued shoes (Russian, English, etc.), wooden clogs, and shoes with wooden soles.”

—Excerpt from the interrogation transcript of Stepan Ivanovich Makarshin, dated October 21, 1943 (POW from May 1942 to September 1943)

“The uniforms of the prisoners in the camp were varied. There were hand-me-down Russian and English trousers and jackets, new and old Finnish jackets, boots, and shoes, and English shoes as well. Except for the Karelians, Finns, Latvians, and Estonians, all the POWs wore special insignia: a white letter V on the fold from the collarbone down on both […]. There were also stripes on both sides of the trousers.”

—Except from the interrogation transcript of arrestee Georgy Andreyevich Chernov, dated July 9, 1943 (POW)

We have to admit either that the Soviet POWs did not work in the places the Petrozavodsk State University historians claim they worked or their interrogation transcripts contain false information. In this case, the question arises as to whether serious scholarly hypotheses can be based on such information.

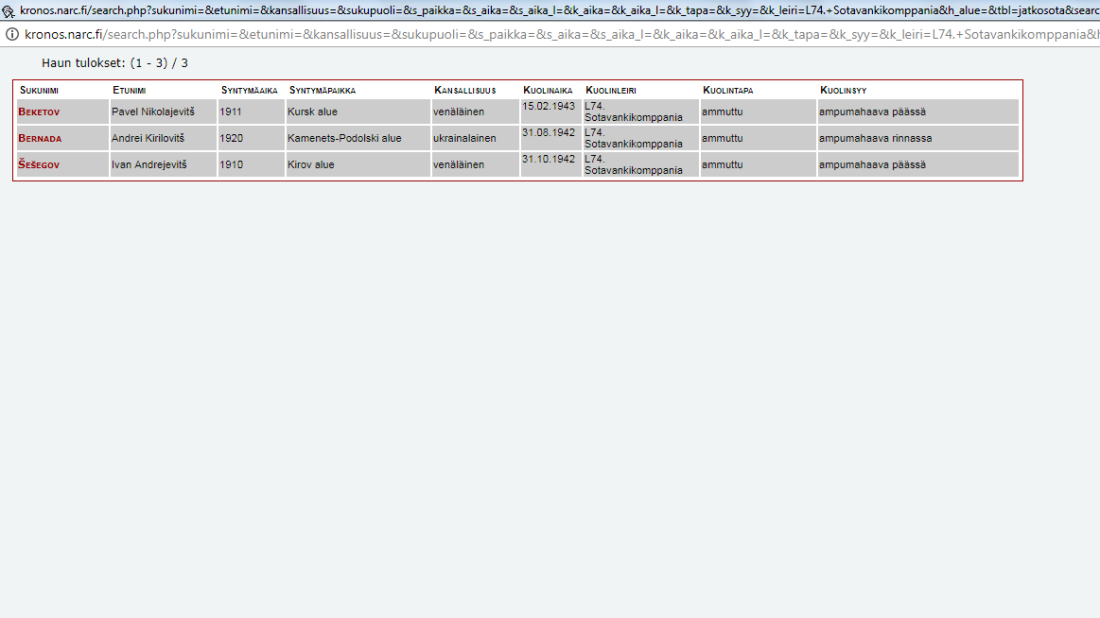

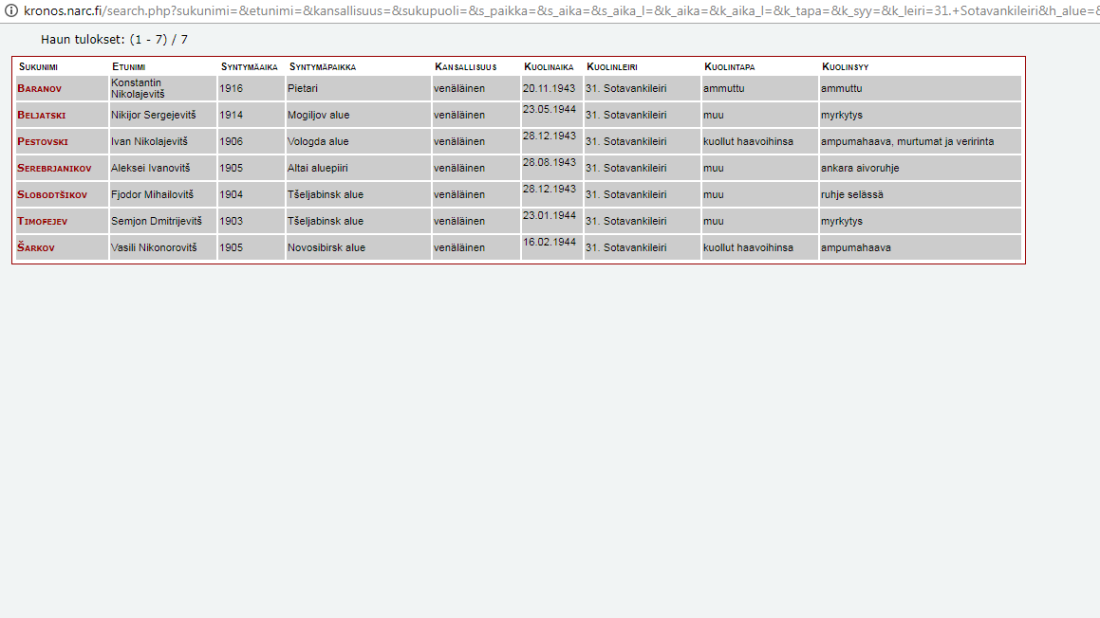

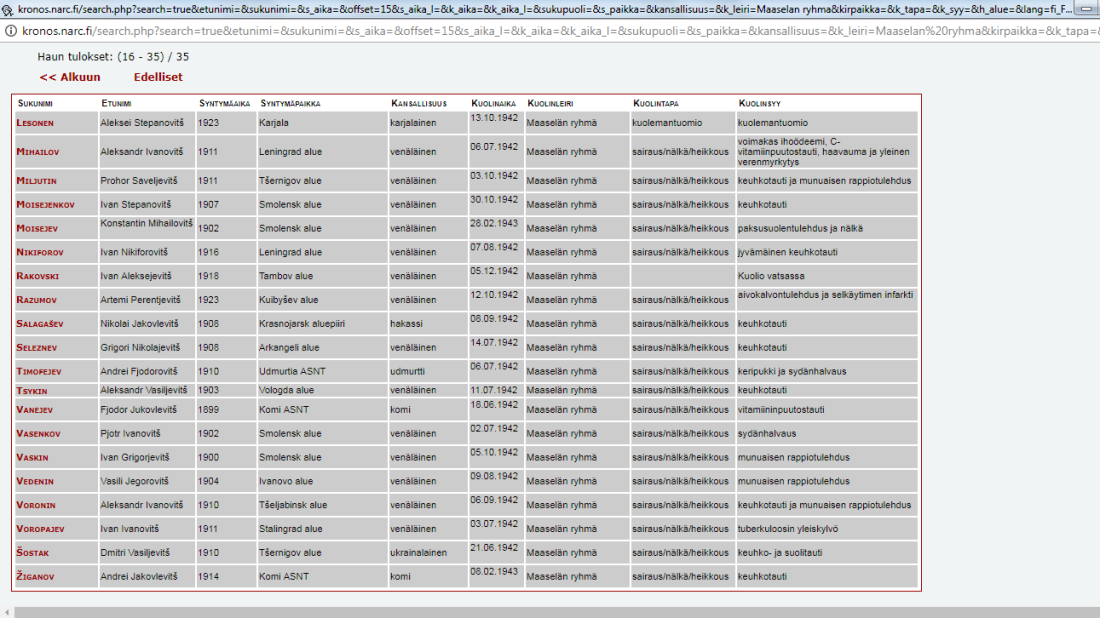

Osiyev was particularly bothered by the fact that not a single former Soviet POW mentioned that mass executions had occurred there. In the Finnish databases there is a list, keyed by surname, of the POWs who died in the Medvezhyegorsk camps from 1942 to 1944.

fi Soviet POWs who died in the Medvezhyegorsk camps from 1942 to 1944, as listed in a Finnish database

Soviet POWs who died in the Medvezhyegorsk camps from 1942 to 1944, as listed in a Finnish database

It transpires that only individual cases are mentioned. But even if we assume that executions did occur after all [in fact, there are eight Soviet POWs whose “cause of death” (kuolintapa) is listed as “shot” (ammuttu) or “death sentence” (kuolemantuomio) in the four screenshots depicted above—TRR], what would have been the point of transporting the POWs or their corpses two dozen kilometers away?

“It was the front line. There was long-range artillery in place there. To bury prisoners [at Sandarmokh], they would have had to have been brought from Medvezhyegorsk, nineteen kilometers away. Who would move a murdered POW along a road leading to the front? All the more so when the archives mention a cemetery in Medvezhyegorsk, that is, in Karhumäki [the town’s Finnish name]. Why would they have moved the dead from the city to Sandarmokh? So, I don’t know why these people [Verigin and Kilin] are doing this. Maybe they want a sensation?” wondered Kashtanov

Map indicating the locations of WWII Finnish POW camps in the Medvezhyegorsk District and the Sandarmokh Memorial

Sergei Koltyrin: Nothing of the Sort Happened at Sandarmokh

Sergei Koltyrin is director of the Medvezhyegorsk District Museum, which has overseen the Sandarmokh Memorial since it was established. When a particular religious confession wants to erect a monument at Sandarmokh, they go through the district council, which forwards the matter to the museum. The museum also monitors the state of other monuments, holds volunteer workdays, and organizes the annual Remembrance Days on August 5 and October 30. Koltyrin calls Sandarmokh an “open-air museum,” a place where popular lectures on the Gulag and White Sea-Baltic Canal are held. But Koltyrin does not see Sandmarmokh only as a museum but also as a place of memory, a cemetery where, he says, he silently converses with the people buried in the ground there every time he visits.

Koltyrin was involved in the July round table at Petrozavodsk State University. His arguments dovetail with those of Kashtanov, but with several additions. Koltyrin is convinced the Finns would not have been able to locate a top-secret, then-recent burial ground, and there was no one who could have told them about it.

“When the first five graves were unearthed [in 1997], there was evidence the people in the graves had been shot in the same way. The Finns did not operate this way. They did not shoot people in the back of the head with a pistol. They had a much simpler system: they sprayed their victims with machine-gun fire and killed them that way. The NKVD had concealed and camouflaged Sandarmokh so thoroughly that everyone was afraid to talk about it. Besides, the majority of the local residents retreated beyond the White Sea-Baltic Canal during the Finnish occupation. People would hardly have been to tell the Finns there was a killing field in these parts, a place where they could kill people. And the front line ran through here. What would the point of bringing people to Sandarmokh have been?”

Koltyrin insisted that to continue pursuing the “Finnish” hypothesis, quite weighty arguments were needed to make the case that such shootings and burials were possible at Sandarmokh. For the time being, however, no one had bothered to show him any documents backing up the theory advanced by Kilin and Verigin. Since there was no evidence, Koltyrin called on researchers not to push “hypotheses for the sake of forgetting the place and obscuring the memory and history of the executions.”

Irina Takala: If the Finns Had Found Sandarmokh, All of Europe Would Have Immediately Known about It

Irina Takala, who has a Ph.D. in history from Petrozavodsk State University, was a co-founder of the Karelian branch of Memorial. One of her principal researcch topics has been the political purges and crackdowns in Karelia during the 1920s and 1930s. Takala was a university classmate of Kashtanov and Verigin. After looking at the documents her colleagues cited, Takala summarized them briefly as follows, “They refute claims about ‘thousands of soldiers tortured’ in the [Finnish] camps, rather than vice versa.”

Takala also had doubts about her colleagues’ true intentions.

“To wonder where POWs are buried, you don’t need ‘newly declassified archival documents,’ especially documents like those. Why weren’t the professors asking these questions ten or twenty years ago? They have been researching the war for a fairly long time. If their objective was to find the dead prisoners, they should have started looking for them near where the camps were located, not along the front lines. So, how is Sandarmokh relevant in this case? So that thousands of executed political prisoners can be turned into thousands of Soviet POWs?”

Takala voiced another important thought about the possible burials of Soviet war prisoners at Sandarmokh. Later, Finnish scholars also echoed this thought in my conversations with them. The thought, it would seem, smashed to smithereens all the possible hypotheses or “sleaze,” as Takala dubbed them, the people attacking Sandarmokh have been spreading.

“I am convinced that if the Finns had discovered Stalin’s mass burial sites, super secret sites, during the war, all of Europe would have known about it immediately. What fuel for propaganda! [Burial sites of Great Terror victims] were located all over the Soviet Union, but they were not found anywhere in the occupied territories. In short, if there are no other documents that have not been shown to anyone, Kilin and Verigin’s claims smack more of political sleaze, sleaze based on nothing, having little to do with historical research, and aimed at Memorial, rather than at paying tribute to the memory of Soviet POWs.”

“I Hope You Don’t Hate Us”: Finnish Historians on the Unlawful Executions of Soviet POWs

In his article in Kaleva, Yuri Kilin claims, “Finland knows very little about POW camps.” It is a serious charge, a swipe at Finnish historians. However, it turned out Finnish researchers had dealt seriously with the problem of the camps, and the academics who have written about the topic teach in various parts of the country, including Turku, Tampere, and Helsinki. They include such scholars as Ville Kivimäki, Oula Silvennoinen, Lars Westerlund, Antti Kujala, and Mirkka Danielsbacka. I was able to interview some of them personally, while I corresponded with other or simply examined their works.

Ville Kivimäki, a researcher at the University of Tampere, studies the social and cultural history of the Second World War. He admits he is no expert on the conditions in which POWs lived. As someone who studies the history of the war, however, it was no secret to him that Soviet POWs had been kept in terrible conditions. A third of Soviet POWs held by the Finns died or were executed, and they had to be buried somewhere.

“I recently visited the mass grave of Soviet POWs in Köyliö: 122 soldiers are buried there. There must be an awful lot of such graves, considering the huge numbers of Soviet POWs who died in Finnish camps. I admit some of the dead could have been buried at Sandarmokh.”

Why were Soviet POWs killed? Why were they treated so badly? Kivimäki hass answered these questions unequivocally in his articles.

“There was no better enemy for Finnish soldiers than the Russians. Since the Civil War of 1918, Russians had been typically dehumanized, imagined as ‘others,’ ‘aliens,’ and ‘savages,’ the opposite of the humane Finns. Finnish wartime propaganda spread these stereotypes, thus sanctioning the murder of ‘monsters.’ This also explains the treatment of their corpses, dismemberment, photography, etc. This was the outcome of propaganda, and it helped maintain the martial spirit, serving as a unifying factor.” (See Ville Kivimäki, Battled Nerves: Finnish Soldiers’ War Experience, Trauma, and Military Psychiatry, 1941–44, PhD dissertation, University of Tampere, 2013, p. 438.)

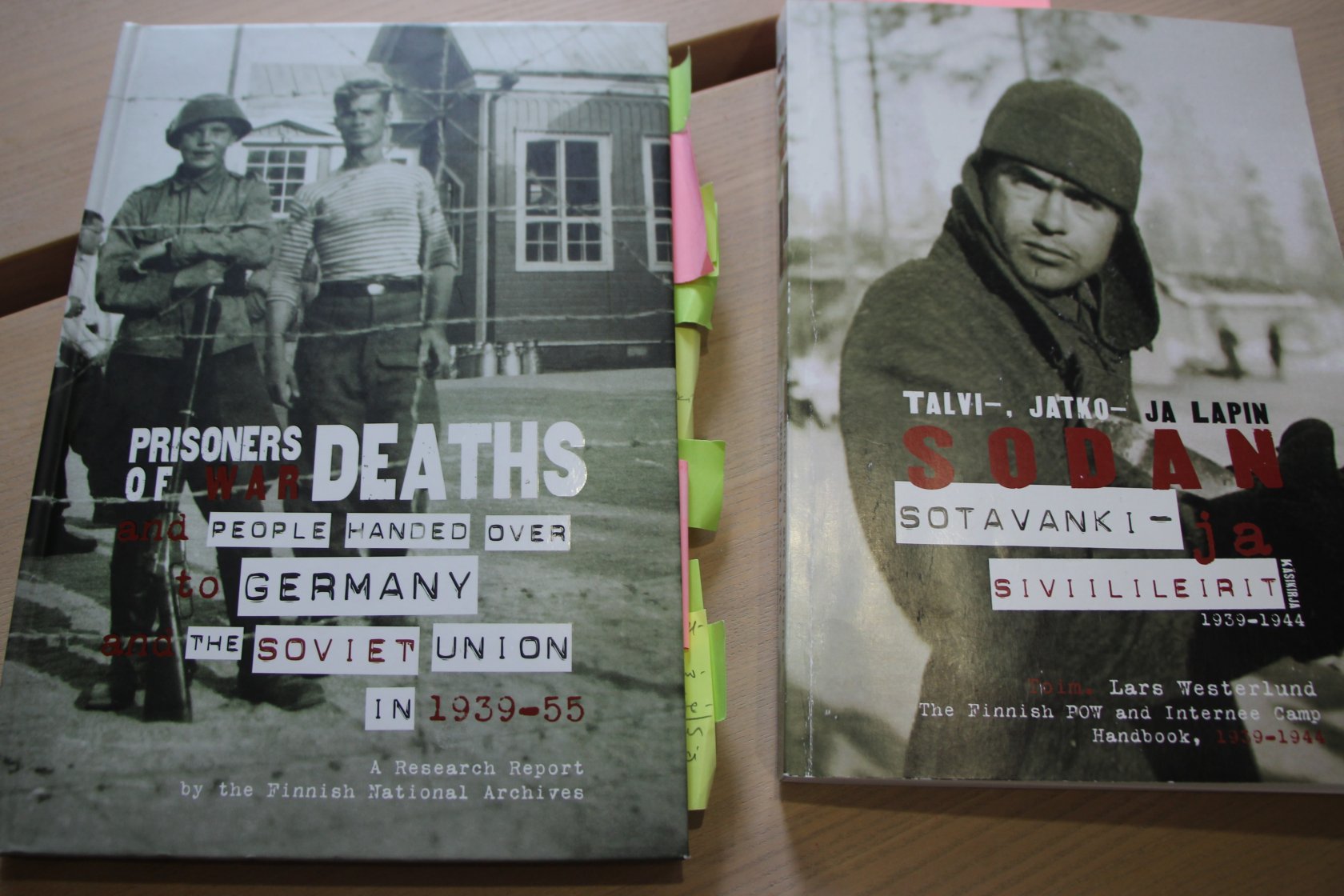

The historian Lars Westerlund has written about the numbers of POWs executed in his works. He directed a project, entitled POW Deaths and People Handed Over in Finland in 1939–55, carried out by a team of researchers at the Finnish National Archives from 2004 to 2008.

Books edited by Lars Westerlund

In Westerlund’s article “The Mortality Rate of Prisoners of War in Finnish Custody between 1939 and 1944,” published in the edited volume POW Deaths and People Handed Over to Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939–55: A Research Report by the Finnish National Archives, mortality figures for POWs are provided per camp. [In fact, no such figures are provided in Westerlund’s article—The Russian Reader.] We read that 6,484 POWs died in the large camps, none of which were located in the Medvezhyegorsk District. Another 3,197 POWs died in medium camps, small camps, and “camp companies” (p. 30). We could probably try and search for the alleged “mass executions and burials” at Sandarmokh among these statistics. The same article cites causes of death (pp. 35–36). 2,296 POWS died “violent deaths” while another 1,663 died of “unknown causes.” Westerlund also mentions that “at least dozens and dozens of prisoners of war were probably killed in prison of war camps without just cause” (p. 76).**

Thus, Finnish researchers do not deny that illegal executions (meaning carried out in the absence of an investigation and trial), including mass executions, took place. But the figures per camp [sic] testify to the fact that “thousands of POWs” could not have been shot and then buried at Sandarmokh, because there were only small camps and POW companies in the Medvezhyegorsk District. [In fact, Westerlund reports that a total of 1,412 Soviet POWs died of all causes in the small camps and POW companies—The Russian Reader.] For this account to sound plausible, we would have to believe that of the probable 4,000 people shot [sic], more than half would have had to have been shot at Sandarmokh, which was only a small part of the long front lines, and moreover not the most tense part.

Since I was unable to locate Lars Westerlund in the summer of 2017 (colleagues said and wrote that he no longer works at the University of Turku and rarely visits the archives), I turned to his colleagues in the POW project, Antti Kujala and Mirkka Danielsbacka.

Mirkka Danielsbacka and Antti Kujala

In 2008, University of Helsinki historian Antti Kujala published Vankisurmat: neuvostovankien laittomat ampumiset jatkosodassa (The Unlawful Killings of POWs during the Continuation War). The book was the outcome of five years of work on the above-mentioned project POW Deaths and People Handed Over in Finland in 1939–55. Kujala is, perhaps, Finland’s foremost specialist on unlawful executions of Soviet POWs. He admits there were incidents in whihch Finnish soldiers shot Red Army soldiers who had surrendered or been wounded. The victims numbered in the dozens. He gives three examples off the top of his head, since while he worked on the book, he researched the archives of Finnish courts, where for several years after the war had ended, alleged [Finnish] war criminals were tried. In several cases, the trials resulted in guilty verdicts, but more often than not the defendants were acquitted. The main reason was a lack of arguments and evidence. Soviet POWs, whom Finland repatriated under the terms of its peace treaty with the Soviet Union, were given the opportunity to testify against Finnish soldiers and officers before they were sent home in 1944. But the information received in this way was not brimming with details, and although it was admitted into evidence in court, it did not lead to the recognition of mass crimes, executions, and the like. Moreover, many Finnish soldiers who were called as witnesses at these trials testified against their former army commanders, and if they had known about such incidents, they would have been revealed in court. On these grounds, Kujala has argued it would be wrong to talk about systematic mass shootings and burials.

At the same time, having thoroughly studied the crimes committed by the Finnish military during the Continuation War, Kujala began our conversation as follows, “I hope you won’t hate us after what we discuss today.”

From the very outset of the conversation, it was clear Kujala was irritated by what he had read in Kilin’s article in Kaleva. (Before our conversation he had only heard about it, but not read it.) He was even more irritated by how the Russian national media had pounced on the Karelian historian’s conjectures.

“The article in Kaleva refers to my [2008] book [on unlawful executions] and interrogations of Soviet POWs who had escaped from Finnish camps. I think the escapees somewhat exaggerated an already unpleasant situation [in the camps], which is understandable. But claiming the German, Finnish, and Japanese camps were the worst is not quite right, and I don’t understand why the author serves up this half-truth. In reality, the highest mortality rates were in the German and Soviet POW camps, while the Finnish camps ranked third. The evidence of mass executions [of Soviet POWs by Finns], as presented in the article, is quite unreliable. The author seemingly follows the simple rationale that the Stalin regime’s crimes were terrible, but other regimes committed crimes as well.”

According to the information Kujala had assembled, the official number of Soviet POWs in Finnish camps, 64,000, was artificially low. Three or four thousand Red Army soldiers who were not officially registered as POWs should be added to this figure. Kujala believes they were executed during or after battles, right on the front lines. The causes of these war crimes were various, from the trivial fear of being shot in the back by a wounded Soviet soldier to a reluctance to deal with prisoners, especially wounded prisoners. Another reason for unlawful executions, on the front lines and in the camps, was the hatred Finns felt toward Russians. In the camps, this was exacerbated by the fact “second-rate” soldiers predominantly served as guards.

“Because all able men were needed on the front, camp guard recruits tended to be those who had lost their ability to fight through having been wounded or because of mental problems, illness or age,” writes Kujala in the article “Illegal Killing of Soviet Prisoners of War by Finns during the Finno-Soviet Continuation War of 1941–44.”

Kujala’s colleague Mirkka Danielsback knows a lot about the relationships between guards and prisoners, and the living conditions in Finnish POW camps. In 2013, with Kujala serving as her adviser, she defended her doctoral dissertation, Vankien vartijat: Ihmislajin psykologia, neuvostosotavangit ja Suomi 1941–1944 (Captors of Prisoners of War: The Psychology of the Human Species, Soviet Prisoners of War, and Finland, 1941–1944).

“I don’t believe that mass shootings of hundreds or thousands of [Soviet] POWs took place. First, everyone was aware that shooting prisoners was illegal. Second, if there really had been incidents of mass shootings, we would know about it for certain, because someone would have talked about it. After researching the archives about conditions in the camps, I can confirm the principal causes of death were not executions at all, but hunger, disease, and hard labor. All this has been documented in sufficient detail.”

Kujala agreed with his colleague and elaborated on her arguments.

“If a considerable number of POWs had been shot somewhere simultaneously or over a brief period of time, this would have necessarily surfaced during the war, although no one could have been punished for it at the time. But it definitely would have come up during the postwar trials. Of course, we cannot rule out anything, if we have no documents [confirming or refuting the hypothesis of mass shootings]. However, we also cannot claim there were mass shootings of POWs. Of course, there were shootings. A dozen POWs could have been shot at the same time, but not hundreds and, especially, not thousands. I don’t believe it. Besides, Finns ordinarily do not solve problems this way.”

When I asked directly whether Kujala believed mass shootings had taken place at Sandarmokh and, therefore, we should look for mass burial sites there, Kujala answered in the negative.

“The most terrible things happened in the Karelian Isthmus, not in Karelia. The largest known unlawful shooting was the execution of fifty captive Soviet soldiers in September 1941.” ( “Illegal Killing of Soviet Prisoners of War by Finns during the Finno-Soviet Continuation War of 1941–44”: 439.)

In his article, Kujala quotes what Finnish researchers know about the numbers of POWs who perished. The Finnish National Archives produced a database on all POWS, including POWs who died. The causes of death have been indicated. Shooting is indicated as the cause of death of 1,019 people listed in the database. Kujala argues we could easily add another 200 people to that number. Thus, a total of approximately 1,200 POWs or 5.5% of all Soviet servicemen who died in while imprisoned in Finnish camps were shot. It would be wrong to suggest or assert that the majority of them were murdered near Medvezhyegorsk and buried at Sandarmokh. In addition, the greatest number of executions of unregistered prisoners, as witnessed by the archives of the Finnish courts, occurred in 1941. The number of shootings dropped off in early 1942, and when Finland came to have grave doubts about the possibility of its winning the war, in 1943, it took better care of the POWs.

Both researchers unanimously affirmed that Finnish historians have done a quite good, finely detailed job of studying issues relating to Soviet POWs and could make reasoned conclusions. One of these was the extremely low likelihood of mass killings and burials of Soviet POWS in occupied territories, i.e., behind the front lines. The largest such incident occurred right after the war broke out, when, in a matter of a few months, tens of thousands of Soviet POWs fell into the hands of the Finns on the southern front, especially on the Karelian Isthmus. It is there, most likely, that it would worth looking for burial sites containing three or four thousand unregistered POWs, that is, prisoners unlawfully shot before they were imprisoned in camps. The possibility there were mass graves of Soviet prisoners at Sandarmokh wasquite low, and the likelihood that mass killings of Soviet POWs took place there was close to zero.

In any case, according to Kujala and Danielsbacka, the camp wardens would not have dared to transport prisoners twenty kilometers away from Medvezyegorsk to shoot them in the midst of constant battles and with the front lines near at hand, and they would have been even less inclined to transport the bodies of murdered prisoners there for burial. All dead prisoners would have been buried right outside the camps. No one would have bothered with the extra work. They would have been buried, if not in the camps themselves, then in places where inmates worked and often died or could have been shot. Kujala and Danielsbacka argued that the hypothesis of mass killings and burials of Soviet POWs at Sandarmokh could not be ruled out entirely if only because there were no archival documents clearly indicating the absence of graves containing the executed inmates of the POW camps in Medvezhyegorsk.

“Finnish Researchers Have Got to the Bottom of the Question”

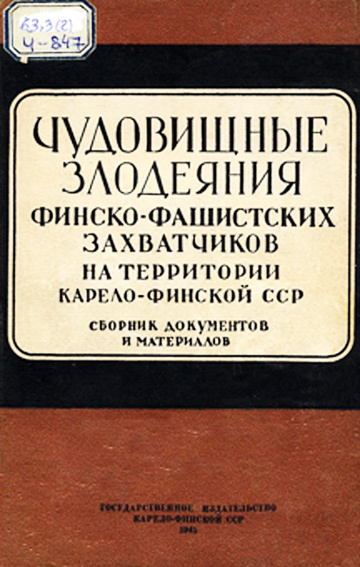

Kujala and Danielsbacka claimed that Finnish researchers had examined the issue in detail. Despite the fact a portion of the documentary evidence had been destroyed in 1944, the main set of documents had survived, and they could be studied freely. In addition, Finnish researchers had also worked in Russian archives and published matter. One such published works is the book The Monstrous Crimes of the Finnish Fascist Invaders in the Karelo-Finnish SSR, published in 1945. The book, however, contains mere references to individual crimes against Soviet POWs, to executions and incidents of torture, reported from the entire front. Researchers are aware that the Medvezyegorsk POW camps are likewise mentioned in the book, but they are certain this is not grounds for making conclusions about mass shootings, and this despite the fact the book should be seen more as propaganda, and less as documentary proof of crimes.

“Repatriated POWs were treated as criminals, in keeping with the Soviet Criminal Code. So the testimony they gave was the testimony of defendants, not of witnesses. In such circumstances, people could have said exactly what authorities wanted to hear them say. I believe the Soviet Union missed the opportunity to obtain really valuable, objective information,” Kujala said.

Silvennoinen agreed with Kujala. In her article “The Limits of Intended Actions: Soviet Soldiers and Civilians in Finnish Captivity,” published in the book Finland in the Second World War: History, Memory, Interpretations (2012), which is used as a Finnish university textbook, she evaluates Monstrous Crimes.

“This report, published in 1945 by a commission headed by General Gennady Kupriyanov, includes eyewitness testimony and documents. It is impossible to credibly affirm the truthfulness of the shocking stories recounted in the report, but the process of assembling the report seems to be a very disturbing sign. In any case, the incidents related in the book did not serve as grounds for actual criminal cases. It seems the report was compiled mainly as domestic propaganda, hence the large print run: 20,000 copies were distributed around the Soviet Union.”

Cover of the book The Monstrous Crimes of the Finnish Fascist Invaders in the Karelo-Finnish SSR (1945)

Cover of the book The Monstrous Crimes of the Finnish Fascist Invaders in the Karelo-Finnish SSR (1945)

Kupriyanov’s report does indeed contain many account of torture and cruelty visited on Soviet soldiers and war prisoners. Many of the stories (see, e.g., pp. 203, 221–223, 257–259, 261–262, 290, 294, 297) were recorded in the Medvezhyegorsk District and include details of numerous executions, some of them mass executions, but these incidents occurred on the battlefield, and those killed were most often were Red Army soldiers wounded in battle. Not even General Kupriyanov’s report contains direct evidence the Finns could have shot hundred or thousands of Soviet POWs in the camps of the Medvezhyegorsk District or buried them en masse twenty kilometers from the city.

A critical attitude towards Soviet sources does not preclude a critical evaluation of of the crimes perpetrated by Finnish soldiers against prisoners. In the same article, Silvennoinen recounts incidents of cruel treatment of POWs and reports of executions. She quotes a directive issued by General Karl Lennart Oesch: “Treatment of war prisoners should be quite strict. […] Everyone should remember that a Russky is always a Russky, and he should be treated appropriately. […] It is necessary to mercilessly get rid of [Red Army] political instructors. If prisoners are executed, they should be marked as ‘removed.'”

Silvennoinen also knows that treatment of certain groups of POWS, not only political instructors but also Jews, for example, was the worst, and it was they who were often marked out as victims of unlawful mass murders. At the same time, Silvennoinen acknowledges that the rank-and-file “imprisoned [Soviet] soldier, finding himself at a place where POWs were assembled and registered, in a transit or permanent camps behind the front lines, was in relatively safe circumstances.” It would therefore be inaccurate to speak of mass executions.

During the Winter War of 1939–1940, 135 Soviet POWs out of a total of 6,000 died, i.e., 2.5% of all prisoners. The figure shows that, despite the attitude of Finns to Russian, which in those years was no better than during the Continuation War, there were no mass shootings of POWs. Indirectly, this might go to show that such shootings could not have become systematic in 1941–1944, either.

When Kujala and Danielsback heard about the idea of assembling an “international working group,” that would engage in affirming or refuting the hypothesis of mass burials of Soviet POWs at Sandarmokh, their reaction was extremely clear.

“I cannot speak for my [Finnish] colleagues, but I would definitely not be involved in the work of some ‘international group.’ After reading the articles published in Russian [on the websites of Zvezda TV and Izvestia], I understand the main idea of the authors or the people who commissioned the articles was to show that the Stalin regime’s crimes were awful, but others committed awful crimes, too. So, we are no worse than anyone else, and they are no better than us. I think that Finnish newspapers, including Helsingin Sanomat, who have quoted Kilin’s article in Kaleva, do not understand these intentions. People who write in articles about mass executions simply invent the truth rather than relying on the facts. Thus, I would place this ‘Sandarmokh incident’ in a broader context. And this context tells us that some people in your country are try to prove that all foreigners and foreign governments are enemies of Russia, which is really quite wrong,” Antti Kujala said.

When the conversation turned to the thought that if the Finns had accidently discovered Sandarmokh, we would not have had to wait until 1997 for it to be discovered, the Finnish researchers nodded approvingly. There was no doubt that the Finnish military command would not have concealed prewar mass burial sites. On the contrary, they would informed the international community, as it would have been a powerful boost to anti-Soviet propaganda. The same thing would have happened as happened at Katyn, which the Germans discovered and immediately reported to the whole world. Therefore, the Finns had been unaware of Sandarmokh’s existence.

Instead of an Epilogue

At the end of a long, detailed conversation, Kujala returned to the beginning of the interview, in which he had spoken about hatred.

“I would write my book a bit differently now. After it was published, other works on the topic, Mirkka’s dissertation and Oula Silvennoinen’s articles, came out, containing new information about the camps and the treatment of POWs. I would now put more emphasis on how the attitude of Finns to Soviet prisoners resembled Nazi Germany’s. It’s disgusting.”

******

In order for the reader to make up his or her own mind about the hypothesis advanced by Kilin and Verigin, we add to all the pros and cons voiced here images of the scanned declassified documents from the Russian FSB Central Archives.

The rest of the scanned documents, amounting to a couple dozen pages or more, can be downloaded from the article’s page on 7X7 by clicking on the series of little black dots that appear in sequence below the first scanned document. TRR

Translated by the Russian Reader

* A search of the Kaleva website turned up 24 mentions of “Juri Kilin,” but not the article in question. Following the practice of many Finnish newspapers, however, it could have been published in the Oulu-based newspaper’s print edition, but not posted online. It would, however, have been fitting to provide readers with the date of the article in question in case someone wanted to find and read it. TRR

** According to Westerlund, the total number of Soviet POWs who died in Finnish captivity from 1941 to 1944 (whether in large camps, medium camps, small camps, POW companies, military and field hospitals, and “other” locations) was 19,085. However, of the Soviet POWs who died violent deaths, he identified only 1,019 as having been shot, while 21 were murdered as the result of “death sentences.” Thus, I do not understand what Yarovaya has in mind in the following paragraph, in which she mentions “mass shootings” and “the probable 4,000 people shot.” The word “shot” is mentioned 16 times in the book edited by Westerlund: one of those mentions occurs in connection with the figure of 1,019 Soviet POWs shot in all Finnish camps, hospitals, and other places of detention during the entire period in question. Nowhere in the book is there any mention of a “probable 4,000 people shot.” Meanwhile, a search of the word “executed” in the same book garnered 18 mentions, but nearly all of these were made in connection with Soviet and German POWs who, after they were repatriated by Finland, were executed by their own governments, not by the Finns. Finally, I should point out, as Westerlund does in his article, that all executions of prisoners of war are unlawful under the Geneva Convention. But that is not the focus of his article. On the contrary, as the heading of one section of the article reads, “The Mass Mortality of Soviet Prisoners of War between 1941 and 1942 Stemmed from Neglect.” In the paragraph that follows, Westerlund explains what he means by neglect: “Signs of this neglect were the insufficient rations for the people in the camps, deficient accommodation, partially inferior equipment, the unsatisfactory hygienic conditions in the camps, inadequate health care, and the harsh and occasionally inhumane treatment of Soviet prisoners of war.” The careful reader will note that Westerlund does not mention “mass executions” among the causes of “mass mortality” among Soviet POWs in Finnish custody. Even “violent deaths” (which included suicides, accidents, bombing, etc., not only summary executions) taken together accounted for only 10% of all deaths among Soviet POWs. Yarovaya’s reference to “4,000 people shot” is all the more surprising because, later in the article, in her discussion with Finnish historians Antti Kujala and Mirkka Danielsbacka, she quotes Kujala, who cites the figure of 1,019 prisoners shot, as arrived at by Westerlund. TRR

Attorney Viktor Anufriev appeared at the event, answering the audience’s questions. He argued that the law in Russia still exists autonomously from law enforcement. Dmitriev’s rights as someone who has been accused of a crime are observed to the extent they permit the authorities to keep him under arrest by constantly extending the term of his detention. Anufriev is certain of his client’s innocence. There is no evidence of a crime in Dmitriev’s actions.

Attorney Viktor Anufriev appeared at the event, answering the audience’s questions. He argued that the law in Russia still exists autonomously from law enforcement. Dmitriev’s rights as someone who has been accused of a crime are observed to the extent they permit the authorities to keep him under arrest by constantly extending the term of his detention. Anufriev is certain of his client’s innocence. There is no evidence of a crime in Dmitriev’s actions.