Source: CASE, “Novaia rossiiskaia diaspora: vyzov i shans dlia Evropy,” p. 13

Russian opposition forces will discuss with European officials the possibility of expanding opportunities for immigration from Russia to the EU countries. One of the measures they propose is a “relocatee card”: the bearer of this document would be able to freely obtain a residence permit in one of the EU countries, open a bank account, rent real estate, and get a job. The authors of the idea argue that the outflow of educated and well-off Russians can weaken Russia’s economic health while also “creating serious challenges to the Putin regime.” They argue this in a study on Russian relocatees in the EU, published on Tuesday, 11 June 2024.

The report was prepared by a new think tank, the Center for Analysis and Strategies in Europe (CASE), whose advisory board members from Russia are Dmitry Gudkov, Sergei Aleksashenko, Vladislav Inozemtsev, Andrei Movchan, and Dmitry Nekrasov. The study will be presented in Paris at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI), which commissioned it. In the coming days, the report will also be presented at the PACE, the German Foreign Ministry, and the Bundestag, Gudkov said.

Portrait of Russian immigrants: good education, high income, anti-war views

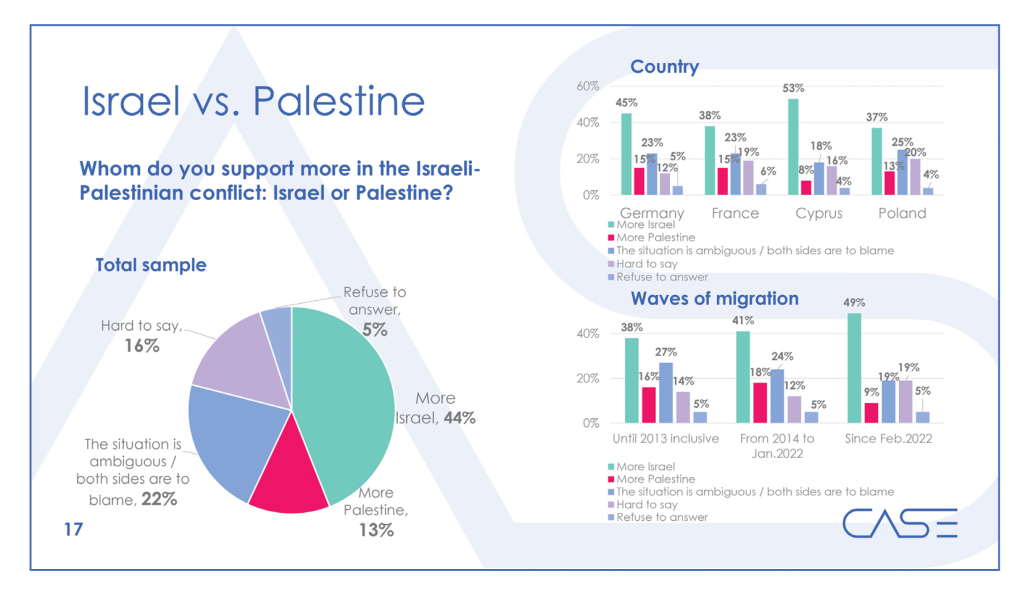

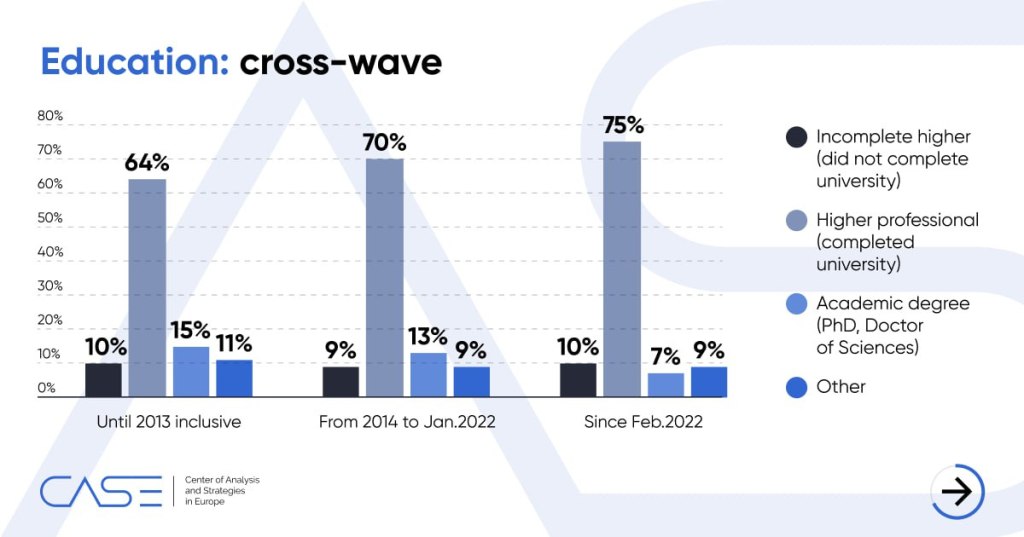

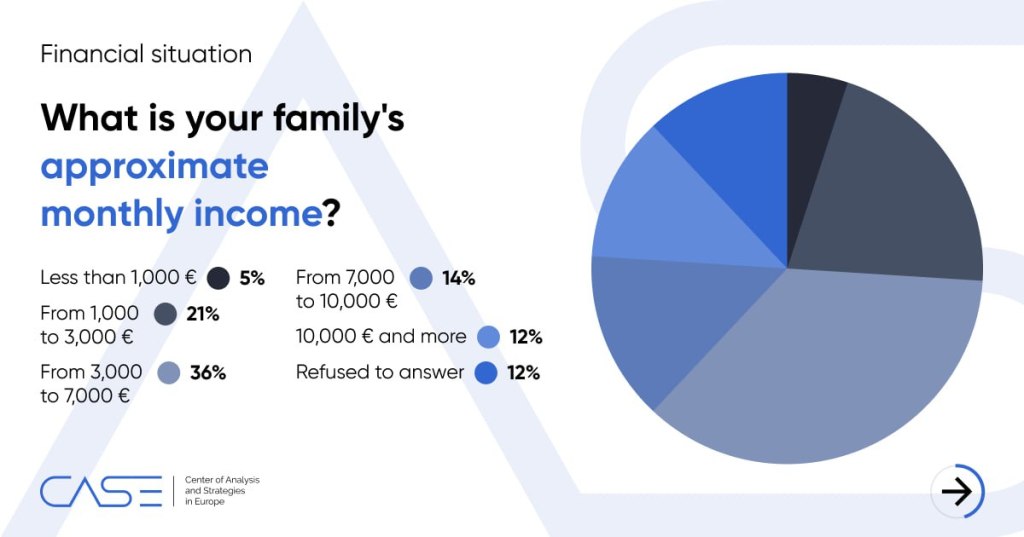

As part of the study, researchers surveyed three and a half thousand Russian nationals residing in France, Germany, Poland, and Cyprus. The results showed that most of those who left Russia after the start of the war in Ukraine — eighty-two percent — have a higher education or an academic degree. Sixty-two percent of those surveyed reported monthly earnings of three thousand euros or more. This category of people, Gudkov said, not only does not require benefits [sic], but also makes a significant contribution to the EU economy.

Among Russians who have relocated to the EU in the past two years, the vast majority oppose the policies of Russian President Vladimir Putin (79%) and support Ukraine (64%). Gudkov emphasizes that most relocatees are well-off, educated people with anti-war views.

“It is important that this is the work of European researchers confirming our long-standing argument that new immigrants from Russia hold European [sic] views. They oppose the war, and can rightly be called ‘Russian Europeans’. They are not a threat and represent an economic and social resource for European societies,” Gudkov told DW.

The infographic slideshow précis of CASE’s “study,” as found on Dmitry Gudkov’s Telegram page

Report’s authors propose “relocatee card” for Russians

The study’s authors suggest that the authorities in the EU countries develop legal norms for the large-scale migration of Russian nationals to the EU, Gudkov said. According to him, Russian nationals now face restrictions in some European countries, including, for example, problems with obtaining residence permits and opening accounts in European banks.

The study proposes a new mechanism for attracting “economic migrants” from Russia to the EU: a “relocatee card,” whose holder could easily open a bank account, rent real estate, and get a job in one of the EU countries. The document, as stated in the report, could be valid for a year with the possibility of renewal. During this “trial period,” the cardholder would have to confirm that they are employed or opened their own business, lived three quarters of the time in the country which issued the residence permit, have a higher education, know one of the European languages, and also own a home or rent one in the EU. Moreover, the study proposes providing evidence of the relocatee’s liquid assets in Russia as proof that they have the means to pay for their stay.

“Today, the strategy for undermining Putin’s regime must include a staged ‘bloodletting’: stimulating the outflow from Russia of both skilled professionals and money from Russian businesses not involved in the war,” the report says. The emerging new diaspora from Russia has political potential: it can play an important role in the transformation of Russia in the event of the fall of Putin’s dictatorship, and thus this community would see “a close and understanding ally, not an enemy” in Europe and the west as a whole, the study emphasizes.

The oppositionists believe that the approximately 300,000 Russians who left their homeland after the start of the war in Ukraine but who want to live in the EU would be willing to apply for the program.

The authors paint a portrait of these Russians: “They are not activists or oppositionists, but are driven by a search for options for a professional career, a risk-free place to live and a country in which their children could be raised outside the culture of hatred that is being created in Russia today.”

The authors of the report also suggest issuing “relocatee cards” inside Russia through European embassies, thus shifting the focus away from tourist visas.

“Relocatee card” not the same as “good Russian passport”

Gudkov insists that the current campaigns is aimed at eliminating discrimination against Russian nationals in the EU and has nothing to do with the idea of creating a Worldview ID system — a database of Russians with anti-war views, which social network memes dubbed the “good Russian passport.”

“That idea, which has been perverted, has already lost its relevance,” the politician explained.

The opposition politician also stressed that, in parallel, the study’s authors also propose that European authorities expand the program of issuing humanitarian visas, for which there is now a waiting list.

“But ninety-five percent of those who have left Russia do not need humanitarian visas. They are ready to work, earn money, and pay taxes. They don’t need welfare checks. We are highlighting them and suggesting various options for resettling them in the EU, which may not necessarily involve a relocatee card,” Gudkov concluded.

Otherwise, he argues, some of the relocatees will continue to return to Russia and restore the country’s economy, while another segment could become disillusioned with the west, “which makes no distinction between the Putin regime and people of modern liberal views who have become its hostages.”

Source: Alexei Strelnikov, “A proposal to European Union to simplify intake of immigrants from Russia,” Deutsche Welle, 11 June 2024. Translated by the Russian Reader

The “relocatees” are indeed the very models of modern major generals:

The Russians who have left also differ in their value system from those who decided to stay. They are much less religious, aligning more with the general sentiments of Europeans; they find it much easier to engage in collective, volunteer and non-profit projects; they display significant empathy — including towards Ukrainians who have become victims of Russian aggression — and are more often inclined to respect other ethnic groups and cultures, as well as showing a willingness to learn the languages of their new countries of residence, regardless of how long they intend to stay there.

Discover more from The Russian Reader

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.