Counting the Ships as They Sail Past: Rikhard Vasmi at K Gallery

Pavel Gerasimenko

March 11, 2015

Kommersant

Over the last few years, Petersburg’s K Gallery has been closely focused on late twentieth century art. The newly opened Rikhard Vasmi retrospective ranks among these exhibitions. It is the first representative, monographic show of the artist’s work since his death in 1998. Featuring around 200 paintings and drawings, mostly from private collections, the show would hardly have been possible to mount during Vasmi’s lifetime.

Vasmi was notorious for the fact that even when he was already counted among the greats of contemporary art, he was reluctant to sell his work and had an extremely negative take on all forms of public permitted activity, regarding exhibitions as a fall from grace for artists, whose job was to paint pictures and work without interruption. Neither then, during his lifetime, nor now has there been anyone else in Leningrad-Petersburg art who thus imagined the artist’s vocation and place in the world. And yet Vasmi was not a sociophobe in the modern sense of the word. He combined a certain standoffishness with a sense of humor and noble manners. It was just that the man had a firm understanding of what mattered most and what was secondary. He knew his worth and did not want to waste his time.

The universally familiar and still encountered type of the landscape painter, easel in tow, might be dubbed a “cold” artist. Rikhard Vasmi was literally such an artist. For the greater part of his life, he earned money through physical labor, was very poor, and was used to getting by with the simplest things. He was one of those who had earned his right to a consistent nonconformism pushed to the limit.

At the turn of the 1950s, Vasmi and several other very young artists —Alexander Arefiev, Vladimir Shagin, Valentin Gromov, and Sholom Shvarts—formed a group they called the Order of Unsellable Painters. The group was bound by close friendship, joint sketching trips, flânerie, and conversations about art. Another member was their mutual friend the poet Roald Mandelstam, who died in 1961. Mandelstam’s poetic images are literally reprised in Vasmi’s paintings: “The evening air is plangent and clean, / The whole city is stone and glass, / Through the blue, blue lane / The sky has flowed into the plaza.”

A decade after the Nazi Siege of 1941–1944, Leningrad was still a postwar city. The facades of buildings were chipped, the central districts still had wood sheds to complement the stove heating in the houses, and a completely rural way of life reigned in the outskirts. And even later, when urban renewal came into its own, and new large stone houses emerged, they would still be interspersed for a long while to come with barracks and allotment gardens in outlying areas like Rzhevka and Piskaryovka.

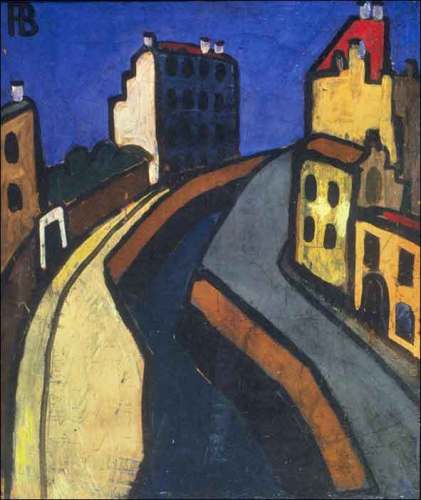

Along with the inner Petersburg district of Kolomna, these were Vasmi’s stomping grounds. It was in these places that the artist produced landscapes that beg the epithet “metaphysical.” But they bear only a superficial resemblance to Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings as they were the product of natural observations made outdoors.

You will not find a work larger than half a meter in Vasmi’s oeuvre. Small formats were a clear token of the period’s unofficial art, but while in Moscow a painting had to be made to fit into the suitcase of a departing diplomat or journalist, in Leningrad it was just hard to secure art supplies without being a member of the official Union of Artists. Vasmi painted in tempera on cardboard and plywood; later, in the 1970s, he often used oil paints.

Vasmi cannot be confused with anyone else, but the significance of his utterly simple visual language changed over the years. The naive manner of the novice painter in the 1950s, who sought maximal contact with reality, has a different meaning than the absolute artistic freedom that ensued in the mid 1970s, when Vasmi produced his pictorial formulation of Petersburg space. The dense surface of his paintings, the way the paints are applied, always leave one with a “house painterly” feeling.

One of the most famous and impressively sized canvases at the show is Canal, dated 1956. The artist has depicted the Griboyedov Canal from a viewpoint unimaginable in reality: the cityscape is seen through the eyes of someone floating in the air, apparently, near the domes of St. Nicholas Cathedral. The painting is heavily cracked, but this is not craquelure, attesting to the piece’s age and thus somehow elegant; here, large chunks of the paint layer resemble cracked sheets of ice, rendering the work even more monumental.

Like his work, Rikhard Vasmi was unhurried, taciturn, laconic, and monumental. All his life he loved watching the ships, and his art conveys the feeling of Petersburg as a maritime city, a feeling found in the work of Leningrad artists of the 1930s, who had reimagined the work of Albert Marquet in their own way. What does the juxtaposition of red-brown and dark blue colors, so frequent in Vasmi’s works, mean? For a Petersburger, it is a rusted ship’s hull in the waters of the Neva, the blank firewalls of houses in Kolomna at sunset—everything that Vasmi’s paintings so clearly and simply depict.

Editor’s Note. Rikhard Vasmi: Paintings and Drawings runs until March 29 at K Gallery in Petersburg.

___________

Rikhard Vasmi, We Work in the Port (Mitkilibris, 1994)

Rikhard Vasmi, We Work in the Port (Mitkilibris, 1994)

On May 16 (27), 1703, on Hare Island, known to the Swedes as Lust Land (Pleasure Land), a “fortress was founded and called Sankt Pieterburch.” (From the Encyclopedia)

The little tug does a big job. In the shallow water, crowded with all sorts of ships, it is indispensable.

The little tug does a big job. In the shallow water, crowded with all sorts of ships, it is indispensable.

The excellent crew of skillful sailors has no time for chitchat. Meeting and seeing off giant ocean liners is all in a day’s work.

The excellent crew of skillful sailors has no time for chitchat. Meeting and seeing off giant ocean liners is all in a day’s work.

Without help from the tug, the huge ship would run aground on a sand bar or crash into a dock. The tug is like a guide dog for a blind man.

In the heat and in rough weather, from morning till night, the little tug crisscrosses the waves.

We Work in the Port, written and illustrated by Rikhard Vasmi, was printed in an edition of one hundred copies by Mitkilibris in Saint Petersburg in 1994. Translated by the Russian Reader.