Per Aspera Ad Astra/Through the Thorns to the Stars (1981), a new version, in Russian with English subtitles.

Soviet film directed by Richard Viktorov, based on a novel [sic] by Kir Bulychev. Music by Alexey Rybnikov (original score); Sergei Skripka (conductor).

Yelena Metyolkina as Neeya • Uldis Lieldidz as Cadet Stepan Lebedev • Vadim Ledogorov as Sergei Lebedev • Yelena Fadeyeva as Maria Pavlovna • Vatslav Dvorzhetsky as Petr Petrovich • Nadezhda Semyontsova as Professor Nadezhda Ivanova • Aleksandr Lazarev as Professor Klimov • Aleksandr Mikhajlov as Captain Dreier • Boris Shcherbakov as Navigator Kolotun • Igor Ledogorov as Ambassador Rakan • Igor Yasulovich as Torki • Gleb Strizhenov as Glan • Vladimir Fyodorov as Turanchoks • Yevgeni Karelskikh

The lone survivor of a derelict spaceship is brought to Earth to recuperate and regain her lost memories. Given the name Neeya, a series of events triggers her telekinetic powers and a number of flashbacks reveal her origins on the planet Dessa. A human spaceship returns her to Dessa. The planet is found to be in ecological ruin and run by a businessman who intends to keep it that way. The crew of the ship, aided by their robot and Neeya’s powers, defeat a monster unleashed against them. They repair the planet’s ecosystem and Neeya remains to help rebuild Dessa while the crew returns to Earth.

Source: Fan Favor Cinematic Plus (YouTube), 28 May 2015 + IMDb

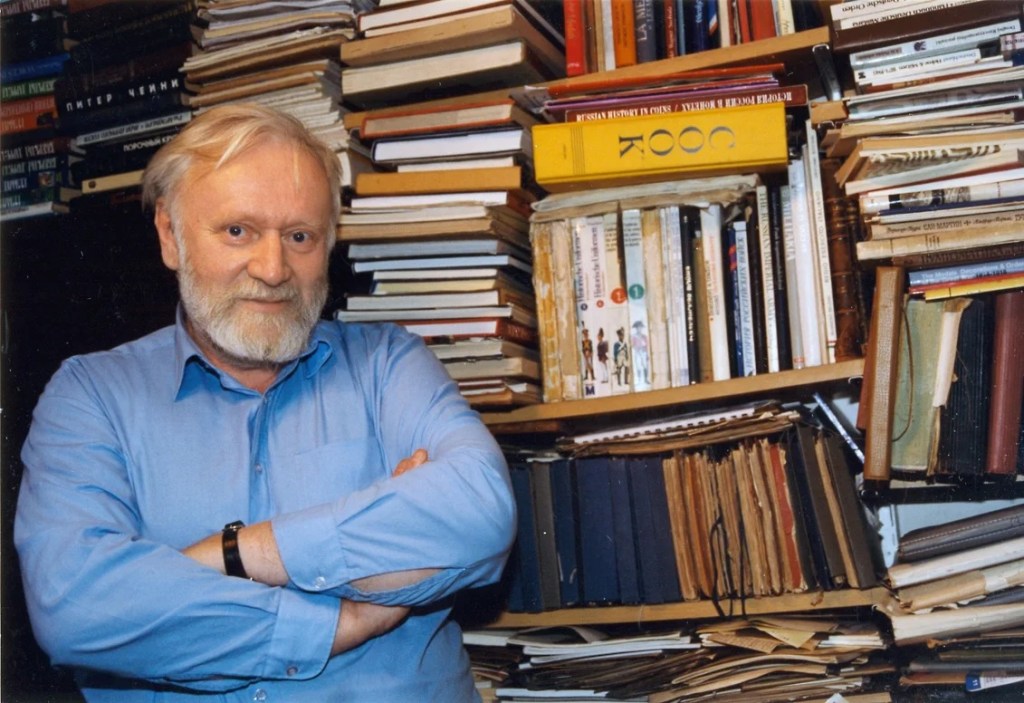

Igor Mozheiko was born ninety years ago in Moscow. Mozheiko was a failed spy, a narrowly focused academic and extraordinarily wide-ranging popularizer and encyclopedist, a passionate collector, a skillful translator, and a great writer. As an author, Mozheiko was renowned under the pseudonym Kir Bulychev, but far from all his accomplishments are well known.

Photo: Ogonyok magazine photo archive/Kommersant

The Darling

The popular take on the happy Soviet era is founded, as we know, on the realities of the final Five-Year Plans. The cultural component of these notions consists almost entirely of cinematic images and lines from movies. The enormous eyes of Natalya Guseva and Yelena Metyolkina, the ominous Turanchoks, the catchphrases “I have the mielophone” and “He will turn speckled purple,” jokes about the android Werther and, of course, the song “The Beautiful Afar” stole the hearts of thousands of Young Pioneers.

Thanks to clever mental gymnastics, for many of these erstwhile Young Pioneers the beautiful afar speaks not from the future, which they would have had to make happen, but from the past, when Young Pioneer ties were redder, ice cream tasted better, and friendship was stronger.

The key creator of this beautiful afar was Kir Bulychev, the screenwriter and author of the literary works on which these movies, TV series and cartoons were based.

It is impossible to argue with this, as well as with the fact that this reputation would amuse, if not offend, Bulychev. He explained the popular love for science fiction by the fact that “any alternative reality was hostile to communist reality,” and in the Theater of Shadows series he turned the concept of yesterday into a dusty boring hell in which scoundrels perpetrate madness.

The cinema noticed Bulychev late, and at first not as a writer, but as an imposing extra. His beard and his friendship with novice actors got the young Orientalist a role in the film Hockey Players (1964) as a silent sculptor who beautifully shares the screen with a portrait of Ernest Hemingway. The first screen adaptation of his work — based on the story “The Ability to Throw a Ball” — happened twelve years later in Alma-Ata, and after that his cinematic career was up and running.

based on a story from his collection Aliens in Guslyar: Photo: Mosfilm

Bulychev’s stories were adapted by both novice filmmakers and the country’s leading directors. A vivid example in all senses is Georgiy Daneliya’s Tears Were Falling (1982). Bulychev’s plots were the basis for comedies (Chance, 1984), action films (The Witches Cave, 1989) and slapstick tragedy (The Comet, 1983). Some of the stories have been adapted more than once. For example, “The Ability to Throw a Ball” was reshot for Central Television twelve years after the first adaptation, and another twelve years later in Poland. The story “Abduction of the Wizard” was made into a two-part television play in Leningrad in 1981, and into a feature film in Sverdlovsk in 1989. It is superfluous to remind readers of the fresh remake of Guest from the Future into the science fiction film One Hundred Years Ahead (which diverges almost entirely from its source), but it does make sense to note that this year the television series Obviously Incredible, based on the Veliky Guslyar series, was released.

In his memoirs, which Bulychev wrote in 1999, four years before his death, he said, “I did not make a noticeable mark on the cinema.” Since then, the number of films, cartoons, and TV series based on his texts has increased by a dozen. Now approaching fifty, this number will clearly continue to grow.

Sanctuary

Kir Bulychev became the number one Soviet science fiction writer in the early 1980s. He was awarded two State Prizes at once — for his screenplays for The Mystery of the Third Planet and Per Aspera Ad Astra, thus revealing at last the real man behind the pseudonym. Previously, few people had known that the mega-popular books were written by an Orientalist specializing in Burmese history.

He proved to be one of the few science fiction writers whom editors were not ashamed to publish and who were safe to publish. This was a massive virtue in an era in which the people in charge were guided by the slogan “Fiction is either anti-Soviet or crap” (said to Boris Strugatsky by a Leningrad filmmaker) or “I divide socially engaged science fiction into two kinds: the first I send to the trash bin, the second to the KGB” (related to Mozheiko by an editor at Molodaya Gvardiya, the only dedicated publishers of new Russian science fiction at the time.)

Photo: Gorky Film Studio

In the early 1980s, the Soviet Union was going through the so-called gun carriage races (a series of funerals for the country’s rapidly expiring leaders) and the unnamed Afghan war, and butter and meat rationing cards were introduced in some regions at the request of workers. Meanwhile, schoolchildren were being readied for nuclear war by taking them out of classes for practice runs to bomb shelters, which in most cases were nonexistent. And the cries of punks (who, according to Soviet propaganda, were exemplars of decadent petty-bourgeois ideology, and sometimes even neo-Nazis), “No future for me,” resounding from the other side of the Iron Curtain, resonated painfully in immature hearts, and they did not presage confidence in the future.

The Olympics proved a poor substitute for the communism promised by 1980. The Food Programme, scheduled to run until 1990, was little inspiration, and the world’s most advanced ideology could not offer any more attractive image of the future. But Kir Bulychev could and did.

He brought Alisa Seleznyova into every home and the dreams of man. Even more importantly, he became a major source of intellectual entertainment, a kind conversationalist and a sensitive shepherd for a vast army of Soviet teenagers. Bulychev’s stories and novels were printed in most children’s newspapers and magazines, which were widely available, unlike the books (especially those with illustrations by Yevgeny Migunov), and anyone could try his or her hand as a co-author. Mozheiko agreed to publish two of his novels in Pionerskaya Pravda in an interactive mode: the author took into account the suggestions and wishes sent by Young Pioneers by mail in each new installment.

Neither children, their parents, nor any normal person could resist the world described vividly and painstakingly in his books: a prosperous, bright and fascinating world with no ideology at all, a world in which a girl can fly not only to the Medusa system, but also abroad, dress beautifully and easily break century-old Olympic records, descend to the seabed in the arms of dolphins, fight with pirates, make friends with Baba Yaga, sit down for a chat with her teacher, know all languages and basically everything in the world, while being friends with whomever she wants. She is A Girl Nothing Can Happen To.

It was a world of private interests and emphatically personal growth rather than a collective existence based on the principle that the majority were always right. It was a world of tenderhearted people, where only pirates were evil and only robots were stupid.

It was a world in which one would like to live, like the Noon Universe of the Strugatskys, only tailored to younger and middle-aged children. “Let’s give the globe to children,” sang Sofia Rotaru, and nobody believed it, but what if we could do it? Everything was free, everything was cool, you didn’t have to die at all, and there were vending machines on the streets dispensing free ice cream and soda of all sorts. And there was no communism, capitalism and other historical materialisms, no Young Pioneers, Komsomol members, Communards and Soviet power, no giant monuments to Lenin looming over Sverdlovsk, as in the early Strugatsky novels. On the contrary, the Stalinist monument to Gogol on the eponymous boulevard was replaced by a pre-revolutionary one, and the boulevard itself was turned into a jungle complete with cypresses, bananas and monkeys.

and then appeared as Polina in Guest from the Future. Photo: RIA Novosti

Such an approach was tantamount to an “Attack!” command for conservative editors and their curators in the security services. But it was Molodaya Gvardiya whose internal reviewers noted that “We know what the author is hinting at when he writes that dark clouds were creeping over Red Square” and also pointed out that the author’s secret goal in “Cinderella’s White Dress” was to discredit Soviet cosmonauts. This review, according to Mozheiko, had been written by Alexander Kazantsev, a veteran Soviet science fiction writer and the prototype of Professor Vybegallo in the Strugatskys’ novel Monday Begins on Saturday. The requirements of the publishing house Detskaya Literatura (Children’s Literature) were milder, and the censorship’s scrutiny of it, more lax.

As a matter of fact, a well-fed future in which carefree children bounce between planets had long been a commonplace in Soviet science fiction, but the world was quite sterilely fantastic, the characters were cartoonish, and the action was forced in the works of Vitaly Gubarev, Vitaly Melentyev and Anatoly Moshkovsky.

As painted by Bulychev-Mozheiko, Alisa’s world is natural and authentic.

The girl with with the Carrollesque name made Wonderland beautiful and desirable.

Few people paid attention to the fact that in the original version of the song about the beautiful afar, as heard in Guest from the Future, the voice summons viewers not to “marvelous lands” (as in all subsequent reprints and collections of lyrics), but “to non-paradisal lands.”

In any case, the voice asks strictly.

An Aerial View of the Battle

Image: Molodaya Gvardiya

According to a popular legend, Kir Bulychev was born by accident. In 1967, the censors removed a translated story from the upcoming issue of the almanac Iskatel (Seeker), which already had a cover featuring a dinosaur in a glass jar. Replacing the cover would cost a hell of a lot of money and threatened the editors with the loss of their bonuses, so the young feature writer Mozheiko overnight came up with a sci-fi story on the given theme, which he signed with a pseudonym inspired by his wife’s name and his mother’s surname, in keeping with the habit of academics of not blowing their cover in in non-academic outings. The editors kept their bonuses, and world literature gained a new author.

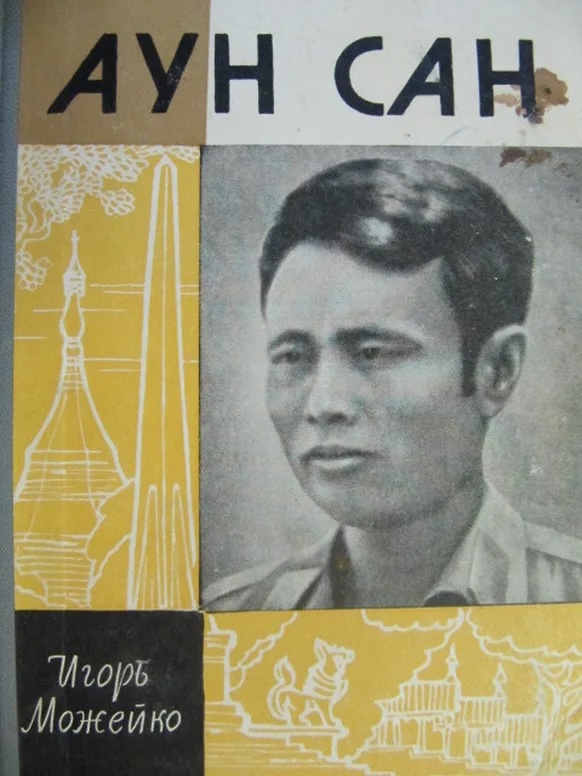

The legend, of course, is false. By 1967, Mozheiko had already published four books, including a very popular one about the Burmese revolutionary Aung San, in The Lives of Remarkable People series. He has also published a couple of science fiction stories under the pseudonym Maung Sein Ji, passing them off as translations from the Burmese. Most importantly, he had published several stories about Alisa under the pseudonym Kirill Bulychev.

As a translator he had debuted a decade earlier, when he published a story by Arthur C. Clarke, which he translated with his childhood friend and future academic colleague Leonid Sedov. Initially, the pals had offered the publisher their translation of an unknown book about a girl who fell down a rabbit hole into a magical land. The young men had no clue about the book’s cult status beyond their one-sixth of the world nor about the existence of at least four previously published Russian translations. But at least one of the failed translators obviously remembered the heroine’s name.

In any case, Bulychev — initially, Kirill or “Kir.”, then just Kir — was born an experienced author with a steady hand, a broad outlook, a constructive mindset and a quite recognizable style. It was a style capacious and not simple even, but simplified at times, almost, to the point of outright silliness. But only almost.

The life of Soviet individuals was subject to a set of unwritten rules that changed markedly from department to department and from decade to decade. Mozheiko learnt them early —because there was no other way.

He was born into the family of a prosecutor from the Middle Volga region and the commandant of the Shlisselburg Fortress. However, by that time the fortress had been turned into a chemical warehouse. His mother had gone into the reserves before her maternity leave, and came to work as a rank-and-file staffer at a chemistry institute. His father soon took the post of Chief Arbitrator of the USSR (a position similar to the chair of the Supreme Arbitration Court), but by that time he had already left the family. Igor’s stepfather, who had fought through the entire conflict, was killed on the last day of the Second World War. Igor and his sister and mother survived bombings, evacuation, a return to Moscow and starvation.

He learnt to read late, fell in love with science fiction early and started writing it, went to a “special faculty for future intelligence officers,” which “was modestly called the translation department of the Institute for Foreign Languages,” and twice dodged KGB drafts (after graduation and as a correspondent for the APN news agency in Burma) and escaped into academia, which he combined with popular science journalism from the very beginning.

As a translator he worked on Zarubezhstroy construction projects in Burma, Ghana and Iraq. As a correspondent for the magazine Vokrug Sveta (Around the World) he journeyed to the most exotic fringes of the Soviet Union, and as a simultaneous interpreter he traveled in Europe and the USA. “Asimov greeted me with a handshake, Harlan Ellison chatted with me, I heard [Clifford] Simak speak, I argued (I was so brazen) with Frederik Pohl, I appeared on the radio with Lester del Rey, and I palled around with James Gunn, but most importantly I spent a whole day drinking with Gordon Dickson and Ben Bova, not to mention his gloriously beautiful wife, Barbara Benson,” recalled Mozheiko. This, of course, was not only unimaginable for most venerable Soviet writers, but also for the so-called Gertrudes — the Heroes of Socialist Labor [Geroi truda] who led the Writers’ Unions for decades.

Mozheiko himself never joined either the Writers’ Union or the Communist Party, flatly refusing the most persistent invitations. The explanation “I consider myself unworthy” did the trick, but just barely. When it didn’t work, Mozheiko changed jobs.

This, by the way, enabled him to keep his beard, since the recruiters from state security, or high-ranking guests like cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova insistently advised him to shave it off. (“As a correspondent for APN, I photographed cosmonauts for our newspaper. Valentina Tereshkova sent back one of the photos I had given to her with the following autograph: ‘Your wife should make you shave off your beard. After all, a person’s dignity is determined by their character, not by their personality.’ Our guest believed that personality was the nose and the ears.”)

Mozheiko was no longer allowed to travel abroad after 1970, but at least he did not go to jail with several of his acquaintances, passionate collectors like him who were handed lengthy prison sentences in the so-called Case of the Numismatists. (Dozens of lines in the indictment amounted to nothing more than “Defendant No. X criminally exchanged one coin for another.”)

And he continued to write.

The Academicians’ Reserve

Image: Vitaly Karpov/RIA Novosti

Mozheiko’s reputation as a supremely tenderhearted storyteller was reinforced by his appearance and his work for Detskaya Literatura, but he was actually quite a tough-minded author. Bulychev’s first novel, The Last War, deals with the aftermath of a nuclear armageddon: even if it was set on another planet, such topics were not encouraged in Soviet literature. A couple of years earlier, a scene depicting a tactical nuclear strike was thrown out of the magazine version of Inhabited Island, by the Strugatskys, and the book edition was put on hold for two years. The release of The Last War in the same series (The Library of Adventure and Science Fiction) seemed to pop the cork, so Inhabited Island was also published, but both books waited twenty years to be reprinted in the capital.

A considerable portion of “Abduction of the Wizard” is given over to a quasi-documentary account of brilliant children killed in childhood by Nazis, pogromists and torpid relatives. In the prologue to the story “A Pet,” the touching rendezvous of a young couple ends with the words, “They were incinerated.” And the protagonist of the later story “A Plague on Your Field!”, whose son has died of an overdose, dooms a outsized segment of humanity to starvation in order to take revenge on the drugs mafia.

Bulychev was also quite decisive in interviews and in correspondence with dissatisfied readers: “I beg you: stop reading me. Spare your nerves.” He spared himself even less, however, and he repeatedly explained this in his final years. “I had no willpower, no courage, no determination to oppose the authorities. Yes, I was duplicitous. I wrote certain things for myself, for my friends. I’m not a battler by nature. Since I lived in our country, I went to my job at the institute and was certain that I would die under unfinished socialism.”

The phrase about his job is significant: censorship troubles occasionally threatened him not only on the literary front, but also on the academic one. A good illustration is the 1966 popular history book about the colonizers of Southeast Asia, With Cross and Musket, whose depth and unconventionality overwhelmed readers and amazed experts. Mozheiko wrote it in collaboration with Leonid Sedov and Vladimir Tyurin. Sedov, his old friend and now a prominent Khmerologist, resigned from the Institute of the Peoples of Asia after Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia. Tyurin, a specialist on Malaysia, was declared a defector and dismissed fifteen years later. (Subsequently, however, he returned safely and was reinstated to his post.) The book has never been reprinted.

But Mozheiko published many other scholarly and popular scholarly books, including those dealing not only with his main subject of study, the history of Myanmar.

It is time to mention the encyclopedia Nagrady (Honors; 1998) and the fact that Mozheiko spent the last ten years of his life as a member of the Presidential Commission on State Honors developing the country’s current system of state honors, based on the traditions of the Russian Empire.

Mozheiko’s fundamental study of piracy, In the Indian Ocean (later published as Pirates, Corsairs, Raiders) also deserves special mention, as well as the absolutely revolutionary monograph 1185, a cross-section of one year in world history, focused on events which the author considered crucial in many senses.

Reviewers noted with some bewilderment that individual people’s motives and feelings are far more interesting to the historian Mozheiko than historical processes and the movements of the masses, and even more so than quotations from the classic Marxist-Leninist authors (defiantly ignored even in a book published on the fiftieth anniversary of the October Revolution).

The River Chronos

Image: Cinema Panorama

The writer Bulychev declared his humanism with his trademark rigor. “There is nothing in literature but man,” he explained in an ancient interview (in 1980). Bulychev’s texts, which are chockablock with miracles, journeys through time and space, incursions of fairy tale into reality and vice versa, are populated by nothing but people, or rather, by what he identified as the typical triad of “man, society and time.” That is why his work is still massively reprinted and, more significantly, still massively read, along with the Strugatsky brothers and Vladislav Krapivin. Other stars of Soviet science fiction have not passed the test of time much less well.

Bulychev pointedly assigned himself on a lower shelf. “If God has not given me the talent of Tolstoy or the Strugatskys,” he said, “I am to some extent willing to compensate for this deficiency through hard work,” while also stipulating, “I can usually spare two months a year for science fiction.” After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the reason for the stipulation, apparently, became less pressing. In any case, the author’s productivity increased manifold, if not by an order of magnitude.

According to his own estimates, Bulychev wrote a total of fifty volumes: a dozen were popular science books, another dozen were children’s science fiction, while the rest were science fiction for adults. Understandably, the most visible and talked about were the works in the Alisa Seleznyova series, almost fifty novellas, most of them pounded out in the post-perestroika years in frankly machine-gun mode. Only the first five or six of them are actively reissued nowadays, which is not surprising.

Almost as popular is the series about Veliky Guslyar: a hundred stories and seven novellas, alternately ironic and mocking, about the inhabitants of a provincial town teeming with aliens, and rife with paranormal phenomena and outright devilry.

Fans of old-school science fiction love the Doctor Pavlish series, about a space doctor facing generally insoluble ethical dilemmas.

Bulychev himself appreciated the River Chronos series, which plays with the twists and turns of Russian history. The author always gravitated to such games: back in 1968, he wrote (with no hopes of publishing it) the story “Misfire ’67,” about reconstructors who accidentally cancel the October Revolution.

And yet Kir Bulychev remains in world literature and in the hearts of readers as a genius of the short story — psychological stories for adults about the impossibility of understanding someone else’s mind and feeling someone else’s love and the fierce necessity of it. These stories are told in the same stingy style, which does not distract from their initially unpretentious plots, which conclude quite unsophisticatedly. But they make you catch your breath for a moment, because you recognize them as familiar — as painful and akin and tenderhearted.

Few people call these texts their favorites and keep them at their fingertips for quick infusions of wisdom, but every few weeks, the story “Can I Ask Nina?” suddenly pops up in social networks, messengers, and private conversations, and like an avalanche, everyone starts asking each other, “Have you read ‘The Snow Maiden’? And ‘Professor Kozarin’s Crown’? And ‘Red Deer, White Deer?’”

The list goes on and on and on.

At the end of the Soviet era, Bulychev explained, “I write only what I find interesting. This is unforgivable from the point of view of a reader who loves science fiction of a certain style and school. But it isn’t a shortcoming to me.”

It is even less of a shortcoming to us.

Source: Shamil Idiatullin, “The kindness ray: Kir Bulychev imagined a lot of things, but knew a lot more,” Kommersant, 18 October 2024. Translated by the Russian Reader. Thanks to Nancy Ensky for the heads-up.